The incessant barrage of threats and counterthreats being hurled between Washington and Caracas is the background (sometimes the foreground) of Sino-Venezuelan relations. Simply put, if U.S. ties to Venezuela were friendly, Beijing would have little to do in this oil-rich state that exports 60 percent of its output to its northern neighbor. Yet Washington has been suspicious of Hugo Chávez since he was elected president during the Clinton administration, and relations have nose-dived under the current presidency of George W. Bush. U.S. secretary of state Condoleezza Rice called in mid-February for an “inoculation” strategy to neutralize Chávez. Meanwhile, Chávez insists that the United States plans to invade Venezuela and uses his enormous oil slush fund to press for Latin independence from Washington. Enter China, searching for oil.

In a search for energy supplies, China has sent political leaders, technicians, and investments all over the world in recent years, finally even to Latin America. In this region, which has about 10 percent of the world’s estimated oil reserves, Venezuela is the land of plenty, with about two-thirds of Latin America’s total. Venezuela is the world’s fifth-largest oil exporter. Although China wants some of that oil, the critical question will be, as Venezuelan analyst Elizabeth Burgos put it in a personal interview, “whether China is willing to run the risk of a confrontation with the United States over a country without much importance except oil.”

BEIJING’S DELICATE TIPTOEING ACT

Chávez does not seem to grasp Beijing’s stance, repeatedly trying to pull China in on his side in disputes with Washington. For example, he has condemned Washington’s refusal to supply spare parts for Venezuela’s aging F-16s and for blocking his efforts to purchase aircraft from Spain and Brazil, using the argument that U.S.-licensed components are used by the Spanish and Brazilian companies. “The gringos are sabotaging and they are impeding,” Chávez said in a speech in mid-January. “Well, it doesn’t matter. We will buy [the planes] from China [or] Russia.” Several weeks later he told supporters, “We could easily sell [our] oil to real friends and allies like China, India, or Europe.”

| Already Beijing is finding dealing with Venezuela a challenge to its proverbial patience as well as an escalating irritant to Washington. |

In mid-2005 the Chinese ambassador in Caracas tried to put a brake on Chávez’s rhetoric in a long interview in El Universal. The ambassador said he understood Venezuela’s wish to diversify its clients but added that “the natural markets for Venezuelan oil are North and South America.” Although conceding that China was cooperating with the Venezuelan government in the expectation of securing access to some of the oil for itself, the ambas-sador’s blunt comments suggested that China still is not convinced Venezuelans are serious and committed enough to pull off the production projects and that China’s interest is strictly commercial. That is, China will not allow Chávez to make it his ally in battles with Washington.

Underlying the tensions between Chávez and China are differing interests. Importantly, both reject a “unipolar” world dominated by Washington. China’s main goal since the late 1970s, however, has been domestic development. Foreign relations are intended to advance (or at least not hin-der) that objective. A government adviser from the Institute of International Strategy in Beijing recently emphasized in an interview that China does not want unrest in the Americas. Such a scenario, or rocky bilateral relations with Washington, might threaten energy and other deliveries to China and thus impede the country’s domestic growth.

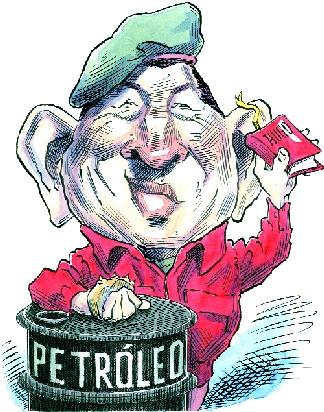

Chávez, however, is a revolutionary firebrand who quotes Mao Zedong and urges major change. One of the most colorful caudillos ever in a hemisphere long famous for its strong and resourceful—rather than brilliant and progressive leaders, he thrives today because he has made himself the cheif spokesman for this decade's wave of Latin anti-Americanism and because Venezuela is now awash in oil money that he spends freely on programs to aid and court the poor and the powerful abroad, which is increasingly resented by many of the poor at home. Latin America is always ripe for such messages because the region’s governments seldom tangibly serve the interests of their people. Also, the United States is sometimes rightly, but often demagogically (in the spirit of traditional Latin scapegoating), linked to those governments and other policy failures. >

| China will not allow Chávez to make it his ally in battles with Washington. |

Chávez wants to develop a kind of “privileged relationship” with China that has a “strong ideological accent,” according to former Venezuelan U.N. ambassador Milos Alcalay. In contrast, Alcalay says, China seeks practical and nonideological commercial ties. Already and increasingly, Beijing is finding dealing with Venezuela a challenge to its proverbial patience as well as an escalating irritant to Washington.

Chávez seeks a special relationship so that China can replace the United States as Venezuela’s chief foreign client, Elizabeth Burgos notes, enabling him to toss the United States out of Venezuela in the context of his continentwide “Bolivarian revolution.” At present, the United States imports about 15 percent of its foreign oil from Venezuela. Late in 2005, Chávez noted that, as long as the United States does not try to invade Venezuela and overthrow him, oil will continue to flow north. In the end, however, this self-styled successor to Fidel Castro seems to think Venezuela must free itself of all economic dependence on the United States. In early February 2006 Rafael Ramirez, the president of Venezuela’s state-run oil company Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), reviewed Venezuela’s oil-related relations with China in a Caracas interview, saying “we are hoping to send 300,000 bpd [barrels per day] to [China] very soon.” This would double the current amount, most of which goes into asphalt. (Much of what China buys now is orimulsion, a low-grade, dirty fuel oil.) Venezuela’s ultimate goal is to provide 15–20 percent of China’s oil import needs. Much of that might have to come from what the United States now receives, for Chinese and foreign sources fear that production is falling, not rising, in Venezuela.

Ambassador Alcalay warns, however, that selling to China rather than the United States is “neither sensible nor realistic,” as China’s ambassador himself suggested, for several reasons. China has no refineries that can handle the heavy, highly sulfurous Venezuelan crude, whereas Venezuela already has its own refineries in the United States that do—the Citgo group. Still more problematic is the long and torturous transportation route around southern Africa and through the dangerous Malacca Strait. The Panama Canal is near Venezuela, but it is too narrow for the very large crude carriers that transport so much crude today. PDVSA has opened an office in Cuba, as it has in Beijing, and plans to build a supertanker shipping terminal at Matanzas, east of Havana. Venezuela says that it will increase its number of tankers from 21 to 58 over the next seven years as part of a shipbuilding program with China and that China could provide some ships of its own. Another option is pipelines. Colombian president Alvaro Uribe and Chávez have already agreed to construct one to a Colombian Pacific port. This route will greatly facilitate transporting oil to China, though Beijing does not seem to be involved in the project.

| Venezuela’s ultimate goal is to provide 15–20 percent of China’s oil import needs. Much of that might have to come from what the United States now receives, for production in Venezuela may be falling, not rising. |

Ultimately, China’s ties to Venezuela must be seen in the context of Bei-jing’s accelerated cultivation of countries throughout the Western Hemisphere. For example, China’s pledges of hundreds of millions of dollars in investments in Venezuela are dwarfed by Hu Jintao’s 2004 pledges of more than $30 billion to Argentina and Brazil alone over 10 years. China is providing some technological equipment to Venezuela, including a communications satellite to be launched in 2008, some computer technology, and three JYL-1 mobile air-defense radar systems. Yet there is no evident master plan here promoted by China. As Ambassador Alcalay says, circumstances are “not favorable for a strong military and intelligence link.” Chávez buys most of his arms from Russia and other military and high-tech goods from anyone who will sell. When it comes to defense matters, he is pragmatic.

In the end, China’s relations with Venezuela are practical and opportunistic. Beijing wants oil but is still far from sure that it will pan out, in large part because of the personality, objectives, and actions of Chávez himself. Moreover, Beijing does not want a fight with Washington. It is conceivable that as their investments rise, the Chinese will become increasingly intolerant of ideology if it reduces competence and efficiency, which it so often does. They may stamp their feet in frustration, much as Americans have done before them. Indeed, before too long Chávez may find that he has replaced “Ugly Americans” with “Ugly Chinese.”

The content of this article is only available in the print edition.