- Budget & Spending

- Health Care

- Economics

The United States will soon confront a major economic problem, perhaps one unparalleled in the nation’s history. It won’t strike tomorrow, next week, or next month, but it is out there, its roots fed by the demographics of the past half century and a body politic hesitant to tamper with aging institutions of government.

Lawmakers procrastinate, pass around blame, and kick the can down the road. Yet our looming fiscal problem is not a Democratic or Republican problem but an American one. And as it draws ever closer, the need for political convergence becomes ever more pressing.

As our federal budget deficits have grown, the level of debt taken on by the U.S. Treasury has risen precipitously. Even a modest increase in the debt would be significant and pose huge risks if we stayed on our current course.

But the challenges in our path are not modest. Over the next twenty years the baby boom generation will nearly double the nation’s aged population, and the baby trough that followed the boom will slow the growth of the working population. The baby boomers and the major advances in life expectancy for subsequent generations will cause a swelling number of recipients of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, and the spending of those programs will soar.

Our looming economic crisis is simply a mountain of debt.

OUR DEBT IS NOT BENIGN

The common denominator of a country’s creditworthiness is its debt as a percentage of what its economy produces each year. It’s a proxy indicator, a way to gauge which nations are overextended and which have their fiscal houses under control.

How high does it have to go to become a concern? How much debt is too much? In 2011, Zimbabwe’s debt-to-economy ratio (debt-to-GDP) was 231 percent; Japan’s was 208 percent; Greece’s, 165 percent; Italy’s, 120 percent. Greece has certainly caught the world’s attention with the fiscal turmoil it has experienced. With the possibility of default, investors got scared. Unprecedented changes in taxes and spending became necessary. Spain and Italy have also teetered on the brink, as have other European nations.

Can we in the United States take comfort because our debt-to-economy ratio was only 68 percent that year? With a lower ratio than that of other highly developed nations, with our Federal Reserve keeping short-term interest rates near zero, and with investors around the world flocking to U.S. Treasury securities as a safe haven, must we really worry? Moreover, while some countries are having difficulty, other countries with markedly higher debt-to-economy ratios than ours haven’t collapsed or sent shock waves around the world.

For many economists, the answer is more complicated than simply noting this ratio. What is the direction of the ratio and how rapidly is it moving up or down? How quickly has a high-ratio country’s economy advanced and what are its prospects? How significant are the commitments its government has taken on? And is the country’s political system stable?

The current level of U.S. Treasury debt and the direction it’s headed are not benign. The United States may be a large and powerful nation and our debt-to-economy ratio may not be as bad as others’, but there is no reason to be sanguine. Our debt will very likely go higher. The climb in our ratio from 63 percent in 2010 to 68 percent in 2011—seemingly modest—raised our Treasury debt by $1.1 trillion. That single year’s rise was larger than the economies of all but 12 of the 190 nations tracked by the World Bank. Absent changes that raise federal revenue or constrain spending, our debt-to-economy ratio could rise above 80 percent over the next three years, exceed 100 percent by 2024, and reach an unfathomable 200 percent by the mid-2030s.

Yes, our economy is advanced and diverse and can produce a lot. And our circumstances differ greatly from those of Greece. But when we look to the future, our spending commitments are enormous. As other burgeoning countries such as China, India, South Korea, and Indonesia expand their economies, their net worth relative to ours will likely grow. Their propensity to generate larger growth rates has been demonstrated. As the Far East and South America continue their rapid spurts, how much more prominent will they become on the world’s economic stage? And what happens to our dollar’s strength then? As our Treasury debt continues its unrelenting rise, will the dollar and our securities still be viewed as a safe haven? Is there possibly a saturation point when investors will say, “We’re looking elsewhere”?

Equally important is that nearly half of our total Treasury debt is held in foreign hands, with most of that concentrated among a relatively small group. Three-fourths of what is owed abroad is held by China, Japan, the major oil-exporting nations, and four other countries and banking centers; 44 percent of that amount is held by China and Japan alone. That makes the debt an obvious national security concern. In early 2010, a shiver ran through the financial markets after China let go of $34 billion of our debt. The Chinese could create turmoil for us by flooding the markets with their dollar holdings. Of course, they would also hurt themselves in the process, and that serves to deter exploitation. But what happens when other countries become increasingly attractive for international trade and development, and our demand for China’s consumer goods becomes less important?

RISKING OUR WAY OF LIFE

The issue is our future risks: to our economy, ability to grow, standard of living, and national security. Today, we may be in a bubble. The dollar is king, and so are our government’s securities. But where will we be in ten years? It’s not just the trajectory of our debt, but what causes it: our government’s propensity to spend more than we are willing to tax ourselves to provide. The level of debt the Treasury has issued publicly could rise to more than $11 trillion, but if we count the debt it owes to the Medicare and Social Security trust funds as well as to other entitlement programs—an additional $5 trillion—our debt-to-economy ratio suddenly rises above 100 percent.

Should we count those other obligations even though they are simply internal debt, IOUs from one arm of the government to another? Yes, because they represent spending commitments already set in law. Lawmakers have the ability to change that, and to raise taxes. However, their steps so far have been no more than hesitant, with little or no change to the fiscal path those commitments put us on. And even if we somehow came up with the money to pay off those debts, we still wouldn’t have enough coming in to pay for all of the future spending committed to those programs. According to the most recent projections of the Medicare and Social Security trustees, even if those internal IOUs were paid off, the programs would run down their legal authority to spend in 2024 and 2033, respectively. Taking that into account, the Congressional Budget Office projects that the amount of federal debt held by the public could rise to 157 percent of our annual economic production by 2032 and 200 percent by 2037. In today’s dollars, it would total more than $30 trillion.

It’s inconceivable that we could run up the national debt to that level. If it existed today, it would equal nearly half of what the entire world produces in a single year. Where are we going to find the investors—at home or abroad—to allow us to generate such debt? It’s one thing when Zimbabwe runs up a debt of 231 percent of its economy. Its annual economic output is only $7 billion; that doesn’t create economic paralysis in world markets. It’s vastly different to think of the United States doing so. Our expected $11 trillion or more in publicly held debt will account for one-fourth of the $45 trillion in outstanding debt issued by all governments worldwide.

As a nation, we have come to treat borrowing as simply another ready source of revenue. But it’s a loan that needs repaying, and as such it’s a claim against future taxes—taxes that may someday fall short because the loan and our spending expectations have grown too large. Procrastination and inattentiveness toward the rising debt of the world’s largest economy will someday catch up with us. The status quo must end.

LOSS OF BUDGETARY CONTROL

In many ways, and through a multitude of provisions embedded in law, the federal government’s spending and revenues are on autopilot.

Indexing provisions tie federal revenues and spending to changes in the economy—to inflation, increases in average wages, the rise in the gross domestic product, and various other economic measures. It’s an understatement to say that the effects of indexing constrain revenue and increase spending. And even though economic times are turbulent and will continue to be so over the coming decade, those indexing provisions are still active, like a faucet left running with little regard for whether the well might run dry.

Of special note is the degree of spending authorized under what are referred to as permanent appropriations. Unlike the hundreds of programs that must receive funding approval each year through annual appropriations bills—so-called discretionary programs—entitlement programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, federal and military retirement, and veterans’ benefits are given indefinite permission to spend through the legislation that governs them. They are on autopilot until Congress sees some reason to re-examine them. These programs have their eligibility criteria and payments to individuals or institutions defined by the laws that created them and are labeled mandatory, reflecting the largely uninterrupted nature of their expenditures. Mandatory spending has grown from 38 percent of the budget in 1972 to an estimated 56 percent in 2012.

The president and Congress have focused on putting the economy back on track with stimulus measures and safety-net add-ons that increase federal spending and curtail revenues. But the public is uneasy with the ever-increasing budget deficits and national debt. Policy makers are aware of the tension, and the public’s unease has resulted in some resistance to enacting additional costly stimulus measures without commensurate offsets.

However, there is considerable reluctance in fiscal-policy circles to stray from the federal budget’s general path. Economists generally believe that tightening the fiscal belt too soon could weaken the economic recovery. Politicians are apprehensive about the public’s willingness to accept large tax increases and a retrenchment of entitlement benefits—that is, raising taxes on middle- and higher-income taxpayers and constraining Medicare and Social Security benefits.

Some people believe the economy can grow its way out of the problem or that painless prescriptions can be found, but the prevailing view among those who study the issue is that neither of these hopes is viable. They fear that if the projections come to pass, the fix will require sudden, severe constraints and economically stifling tax increases. But the view among fiscal-policy watchers is that the earlier we adopt serious change, the smaller it needs to be. That window, however, grows smaller every year, as the baby boom retiree cohort grows larger.

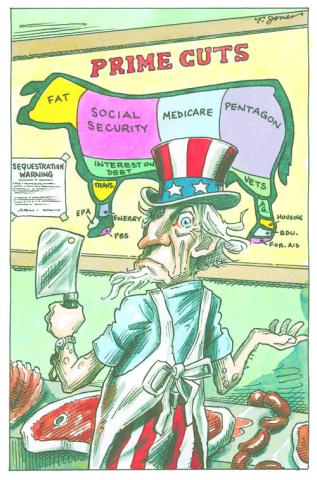

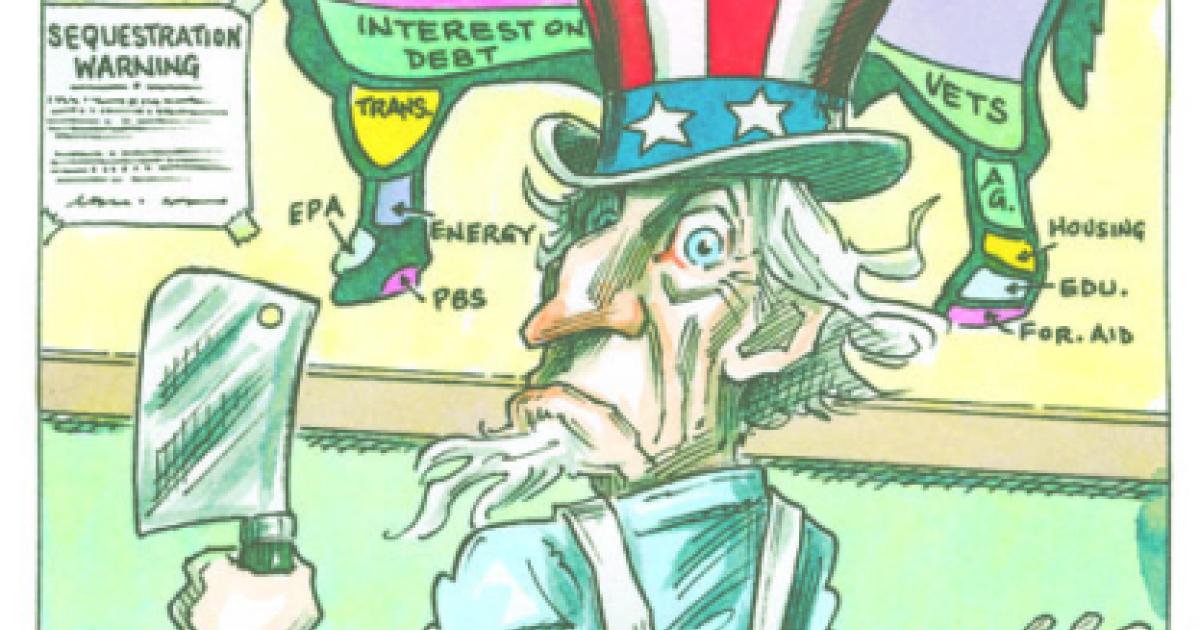

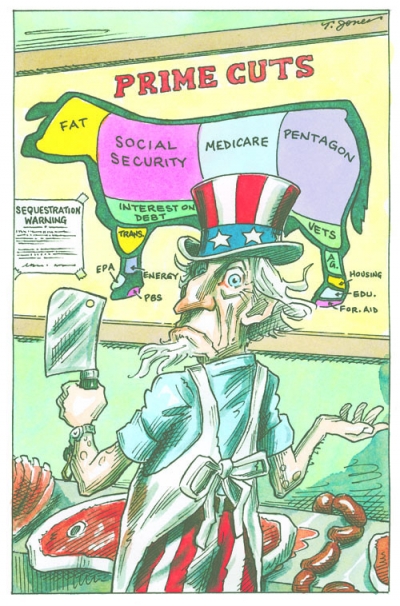

SO WHERE DO WE LOOK?

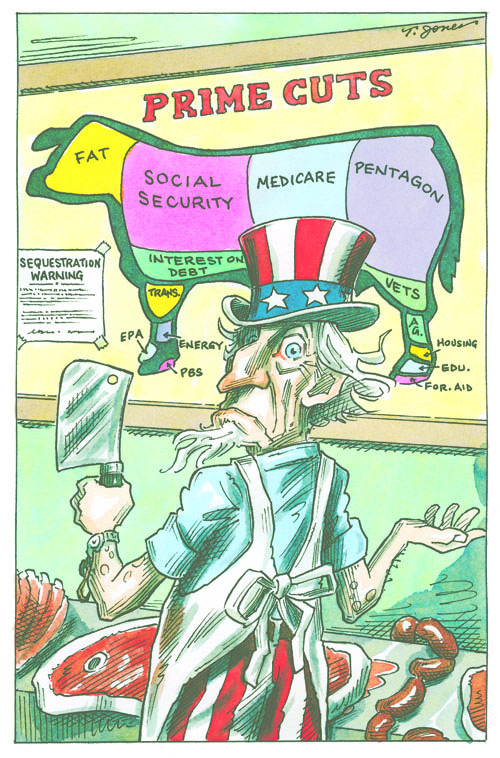

Many want to blame the deficits on a surfeit of wasteful programs: extravagant earmarks, bridges to nowhere, defective weapons systems, fraud in Medicare and Medicaid, noncompetitive contracting, pork-barrel politicking, and congressional perks. All those targets may be valid, but on the whole they suggest an inadequate prescription: that the budgetary hole can be plugged by weaning out “bad” spending. The premise is “just cut the fat; no need to slice the muscle.” The problem is distinguishing between the two.

Discretionary spending is the one area where Congress exercises considerable choice. These programs comprise 37 percent of the budget, and the public suspects an abundance of excess and wasteful earmarks are to be found there. But attacking overspending in these programs may bring little in return. Disclosures of waste by the military notwithstanding, effective armed forces are costly. And while spending on defense and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has been quite large, even at its current elevated level it is only 18 percent of the budget. Welfare programs are 10 percent of the budget; education spending, 2 percent; the National Institutes of Health (NIH), 1 percent; farm programs, less than 1 percent.

There may be a multitude of discretionary programs to explore for savings, but as many budget hawks have observed, it’s hard to take them on en masse. Special interests will rise up in arms. Every lawmaker’s district has something to protect. The fight for small savings is almost as hard as that for bigger ones.

The big money lies with Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security benefits. Nearly fifty million people have Medicare coverage, some seventy million are enrolled in Medicaid at various times during the year, and fifty-seven million people collect Social Security benefits. The big three are the major drivers of the long-range escalation of government spending.

Federal taxes as a share of the economy sit close to their lowest level in sixty years: 15.7 percent in 2012. Taxes have absorbed about 18 percent of the economy since the early 1950s. But even if they were to return to this historical average, they would be no match for the dramatic increase in federal spending over the next two decades driven by the big three entitlements and growing interest on the debt.

Policies that raise lots of revenue or significantly constrain spending—balanced or not—are assuredly contentious. Arguments aside, we as a nation want our taxes low and our entitlements comprehensive. For many years we borrowed to satisfy those desires, but the clock is ticking down toward a day of debt reckoning, and the old strategies will no longer work.

A nation deep in debt is no different from an overextended individual or family. Like any other debtor, it needs to tighten its belt. As the wealthiest nation on earth we can do so while still protecting the poor and disabled, although the politics of retrenchment are hardly inviting, in that they cause heartburn for politicians of both parties. But clinging to the premise that government can protect society only by spending hundreds of billions every year on rich and poor alike is false savings. Somewhere along the way, a generation fortunate enough to be living in the most prosperous of times has lost sight of a core tenet: you cannot have what you cannot afford or refuse to pay for.