- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- Immigration

What policy should America adopt toward illegal immigrants from Mexico? One view is that they drive down the wages of American workers, burden taxpayers, and undermine the integrity of American culture. That view is embodied in the recent immigration bill passed by the House of Representatives: It seeks to seal off the border and treat immigrants who are already here as felons.

A second view is that Mexican immigrants increase the competitiveness of the U.S. economy. That view is embodied in the recent immigration bill passed by the Senate, which would make it possible for illegal immigrants who have been in the United States for more than five years to obtain a visa and eventually citizenship—provided they learn English. It also contains provisions for workers who have been here for less than five years to either obtain a green card or become a guest worker, after they return to Mexico and make the necessary applications.

Just the Facts, Please

Any serious attempt at reform needs to take account of facts regarding illegal immigrants that are often given a backseat to ideology by partisans on either side of the debate. Any serious attempt at immigration reform also needs to take account of facts about Mexico's fragile economy and democracy—facts that both sides in the debate have tended to miss entirely. Indeed, most discussion about immigration reform implicitly assumes that its effects stop at the border. The truth is that our immigration policy is more consequential for what happens to Mexico's political and social stability than it is for America's economy or cultural integrity.

| The impact of immigration on American culture is not determined by what immigrants do but by what their children and grandchildren do. |

Those who favor a “soft line” on Mexican immigration often simultaneously argue that Mexican workers make American industry more internationally competitive and that Mexican workers do not

reduce the wages of U.S.-born workers. Both statements could simultaneously be true if Mexican immigrants included large numbers of highly educated electrical engineers and molecular biologists who had a tremendously positive effect on American total factor productivity. But Mexican immigrants tend to have very low levels of education by U.S. standards; they also tend to cluster in industries that produce goods that do not enter into international trade, such as restaurant meals, home construction, landscaping, and janitorial services.

The overall effect of Mexican immigration on the U.S. economy is trivial—almost certainly less than one-tenth of 1 percent of GDP. Moreover, to the degree that Mexican immigration makes some industries more internationally competitive, it does so by reducing the wages of the U.S.-born workers in those industries. The reduction is not trivial. Careful research done by Harvard's George Borjas indicates that Mexican immigration has caused a 7 percent decline in the wages of U.S.-born high school dropouts and a 1 percent decline in the wages of workers with only a high school diploma. Score one for the hard-liners on immigration.

Assimilation by Generations

Hard-liners, however, have it wrong about the social and cultural impact of immigration on the United States. They tend to look at recent immigrants and decry their low levels of education, difficulties with the En-glish language, and propensity to choose marriage partners from their own immigrant group. They tend to ignore that every other large-scale immigrant group in the history of the United States—Poles, Italians, Irish, Eastern European Jews—had many of the exact same social and cultural characteristics.

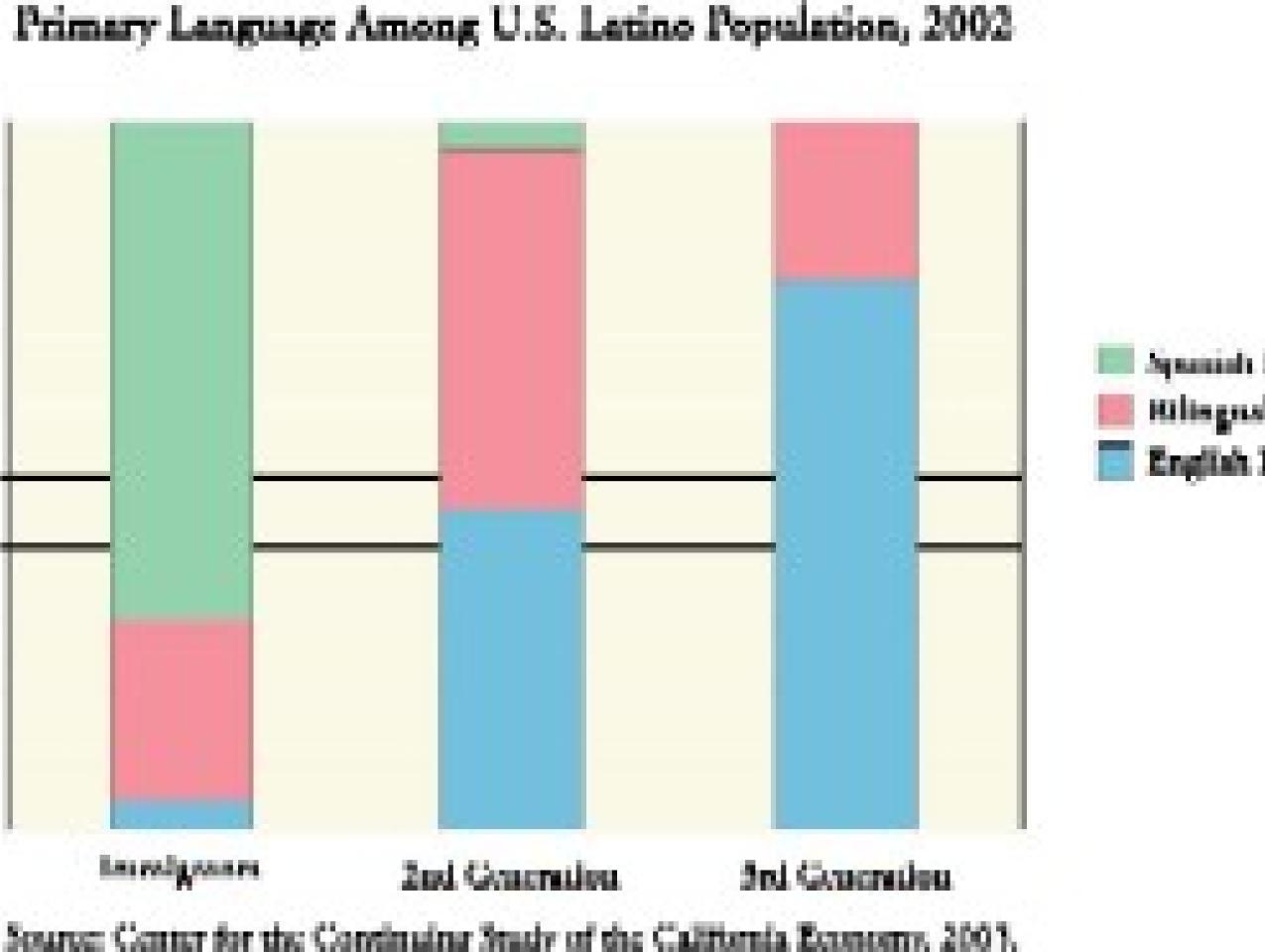

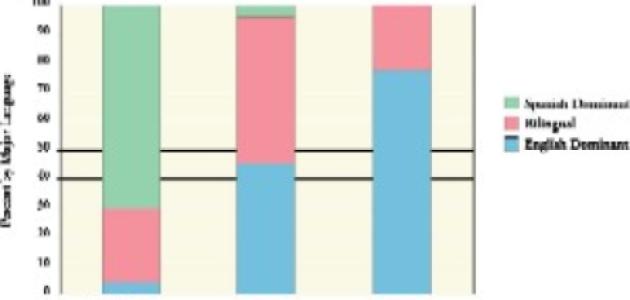

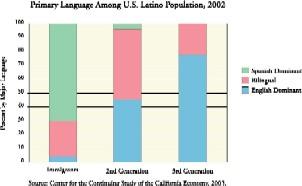

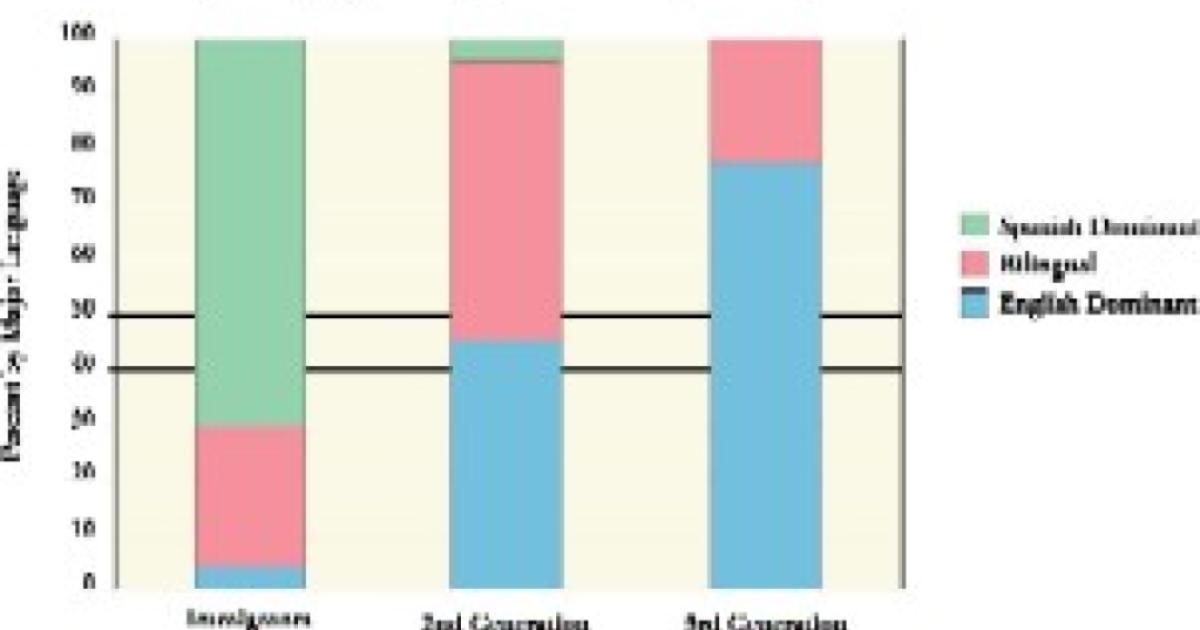

The impact of immigration on American culture is not determined by what immigrants do but by what their children and grandchildren do. Here the evidence is unambiguous: the children and grandchildren of Mexican immigrants assimilate and move up the income ladder. Meticulous research by James Smith at Rand demonstrates that second- and third-generation Mexican-Americans quickly overcome the educational deficit faced by their immigrant parents and grandparents. As a result, they do not constitute a permanent economic underclass; they have been steadily narrowing the income gap with native-born whites. Neither do they constitute a social and cultural group independent of mainstream America. The reason is clear: 80 percent of third-generation Mexican-Americans cannot speak Spanish (see figure 1). Score one for the soft-liners on immigration.

| Any serious attempt at immigration reform needs to take account of facts that are often ignored by partisans on both sides of the debate. |

Immigration Policy Doesn't Stop at the Border

Both sides in the immigration debate have it wrong, however, when it comes to one core assumption: that Mexican immigration is only a domestic policy issue. What we choose to do will have serious ramifications for Mexico.

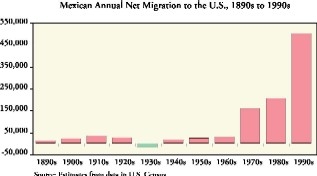

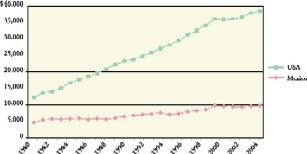

To understand why, we need to take into account that the large-scale immigration of Mexicans to the United States is a recent phenomenon (see figure 2). Until the 1980s, Mexicans crossed the border and worked in the United States in large numbers, but they tended to return home after only a few years. As a result, the number of immigrants who came to the United States and stayed permanently was on the order of 25,000–50,000 people per year. In the 1980s that rate surged to roughly 200,000 people per year, and in the 1990s it went through the roof, averaging 500,000 people per year. The reason is that the Mexican economy collapsed in the early 1980s, and since then Mexico's per capita GDP, adjusted for inflation, has grown at a staggeringly slow 0.7 percent per year, less than one-third the U.S. rate (see figure 3).

There is little reason to think that the Mexican economy will recover any time soon. Indeed, all the fundamentals, most particularly the preference of foreign multinational companies to site new facilities in China instead of in Mexico, point toward continued slow growth.

What would happen to Mexico if we were to suddenly cut off the escape valve provided by immigration to the United States? Unemployment and underemployment, already major problems, would increase dramatically. Remissions from immigrants, which total some $18 billion per year and are the lifeblood of many rural communities, would dry up. The widespread frustration felt by the population caught between rising crime and diminished economic expectations—which fueled the populist presidential campaign of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador—would almost certainly become more acute. There is no scenario in which these developments would be positive for Mexican political and social stability. And there is no scenario in which a politically and socially unstable Mexico is in the interest of the United States.