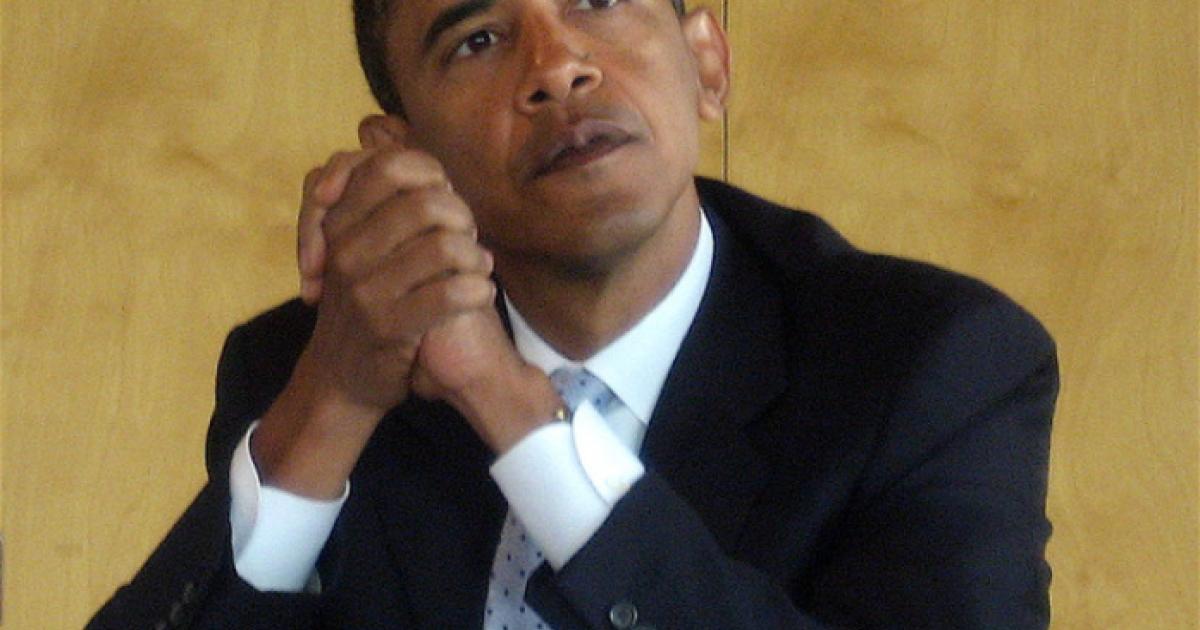

It has now been just over one year since President Barack Obama delivered a confident White House address explaining how the United States and its partners would be able to counter the Islamic State—which, in 2014, he claimed was neither Islamic nor a state. A year later, as we mark the fourteenth anniversary of September 11, ISIS is still very much Islamic and ever more entrenched as a rogue state. Obama’s 2014 speech about ISIS paved the way for the political and humanitarian crisis that we are now facing one year later. There are no surprises here: Bad consequences follow when a United States President thinks that he can counter forces of terrorism and world disorder on the cheap without the use or threat of ground forces.

His mistake was evident, even at the time. He told us “what the United States will do with our friends and allies to degrade and ultimately destroy the terrorist group known as ISIL.” The word “ultimately” said it all. There was no urgency, no timetable for success, no awareness that the individuals who are being raped, killed, and terrorized cannot afford to wait for “ultimately.” They have to survive immediate threats, and a promise to “degrade” an enemy someday is no promise of assistance at all. His speech was an unambiguous signal to these people that they are on their own.

If the ends in question were too timid, the means chosen to realize them are too weak. There is no way in which sporadic airstrikes, however well conceived, will be able to counteract terror that operates on the ground every hour of every day. Yet the President told his enemies all they needed to know when he stated that “we will not get dragged into another ground war in Iraq.” Or, he might have added, in Afghanistan, Syria, or any other place where innocent individuals are slaughtered.

Given Obama’s rhetoric, our enemies know that they have a clear field of operation. The stirring words that the President will “hunt down terrorists who threaten our country, wherever they are,” carried with it two dangerous caveats, both realized. First, he was not prepared to hunt down terrorist who threatened millions of other innocent lives. His speech was to the voters of the United States, not to the millions elsewhere who have no one else to whom to turn. Second, he also signaled unambiguously that he would not use ground forces as part of his hunt. The pathetic support measures that he addressed were doomed to failure from the outset. Without American leadership and planning on the ground, the effort to fight a proxy war is doomed. The military debacles in Syria and Iraq come as no surprise. “Too little, too late” is not a viable foreign policy.

In making this condemnation of presidential weakness, I am not insisting that his ineffective behavior is necessarily a violation of any legal duty that the United States faces. To be sure, there is always the right of any individual, or any nation, to come to the aid and assistance of those who are in need. But there is of course no legal obligation that one must do so, just as there is no legal obligation for any person to use force in self-defense: he can just be still if he wants and face the consequences.

The moral question is of course far more difficult. Should people stand aside when a small intervention can save a life, just because they are under no duty to rescue the innocent victims? The same hard choices arise in international affairs. The question of whether to intervene, at some peril, to help others outside our borders is a moral choice.

It is of course permissible to plead prudence as a reason for inaction. That is what, for example, what The New Yorker did after Obama’s 2014 speech. Even the modest steps that the President proposed in that speech, it was argued, would drag us into war on the backs of “an untested client regime in Baghdad,” which could only lead to further involvements. Prudential arguments of this sort also have to evaluate what will happen by staying out. Ultimately, the question here involves one of political judgment on what to do in the face of a looming political disaster.

Back in 2014, the President did not say how he would cope with the massive and looming refugee problem for one simple reason: He had no idea it was coming. But come it did—and if the United States will not organize protection for people where they live, they will give up their homes and businesses in a desperate search for protection, not only from the Islamic State, but also from Assad’s butchery in Syria, and the sectarian conflicts that have flared up all over Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Though few predicted the rapidity with which the situation would degenerate, it was easy to see that some disaster would soon strike. Why? Because the President does not believe in Pax Americana, the foreign policy approach that states that world peace can only be obtained if the United States is prepared to use force to crush—not just degrade—those that pose a threat to the lives of millions of people across the globe. Make the United States a bystander, and evil nations will wreak havoc on the international scene.

It does not really matter how or why the President came to think that he could secure world peace on the cheap. But the key point is that whenever he is faced with major foreign policy problems, his first move is to take a pot shot at the United States in particular and Western civilization in general. It was not just a verbal slip, but a planned speech, when the President at the National Prayer Meeting breakfast in February 2015 uttered this flip but fatal remark: “Lest we get on our high horse and think this is unique to some other place, remember that during the Crusades and the Inquisition, people committed terrible deeds in the name of Christ.”

Let us give the President the benefit of the doubt and assume that everything he said about the Crusades and Inquisition were spot on. He still forgot that there is a time and a place for presidential candor, and that was not it. The one-sentence mention of the Crusades was especially galling because it conveys the message that the Islamic State is on par with Western civilization. His short statement signaled to oppressed people everywhere that the United States will not get off its high horse to help them where they need it most: in their homes, schools, and markets. How could that disinterested attitude not embolden our enemies and demoralize our friends?

Moral relativism is a poor substitute for presidential leadership. The entire matter would have taken on a very different tone if the President had used his platform to deliver a decidedly different message about the Crusades and the Inquisition: One of the great capacities in Western civilization is to learn from its mistakes so that the errors, and there were many, are corrected. But there is no such impulse among the terrorists of ISIS, whose fierce fundamentalism snuff out the civil society, so prized in the West, that makes moral self-correction possible. Against people like this, persuasion is of no value, so force must be used. Obama’s ill-chosen words contained no ringing endorsement of the moral chasm that separates us from our opponents.

And so the inevitable happens: There is a mass exodus of refugees followed by human tragedy. Right now, the European migrant crisis has resulted in impossible strains on the simple physical capacity of various nations, hard-strapped by their own weak economic position, to provide food, shelter and elementary sanitation for the tens of thousands of refugees that have been driven from their homes. Public health officials and private charities struggle to keep up with the endless demands for services. Thousands more are surely on their way. Just recently Germany, the most generous of the European nations, has announced that it will impose border checks to staunch the anticipated migrant flow.

There is not the slightest recognition on the part of the President that his feckless policies have contributed to this disaster. His most recent 9/11 speech could have acknowledged the need to counter ISIS with real force. But no, instead of any serious engagement with the issue, we were given a two-pronged approach from the White House.

First, don’t bother to say anything of consequence about the failures of the past year. Instead call for a day of remembrance.

Second, puff up the Iran Nuclear Treaty—even though releasing billions of dollars to the Iranians will only increase their funding of terrorist activities in the Middle East and beyond. The resulting political instability will only exacerbate the human migration tragedy that is taking place today.

Right now, the President is looking like a tragically weak game theorist. He thinks that he can achieve successful outcomes in international affairs by using all carrots and no sticks. It won’t work against enemies who are prepared to use both. Unless he rethinks his self-imposed limits on the use of force, the bill for his mismanagement will come due, and everyone will pay the price—during his term and beyond.