- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

Secretary of Defense Robert Gates has been forced to recant. He had promised military leaders last spring they would be able to keep any savings they produced by scouring their budgets. They dutifully identified $100 billion across five years they would shift to higher priority uses in order to reduce future outlays. These were not budget cuts, Gates assured them, but budget redirections and reinvestments.

At a Pentagon briefing on January 6, 2011, Secretary Gates said "the goal was, and is, to sustain the U.S. military's size and strength over the long term by reinvesting those efficiency savings in force structure and other key combat capabilities."

But the spending to be redirected by military leaders ultimately became budget cuts when the White House recently decided it needed to respond to public concern about the debt. That the White House is targeting defense for spending cuts is an unwise decision, especially since the bulk of this country’s fiscal woes can be traced to non-defense related spending. Yet, defense cuts were the only spending reductions the president announced in his State of the Union address.

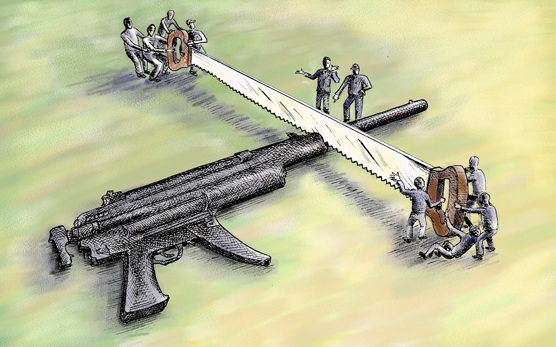

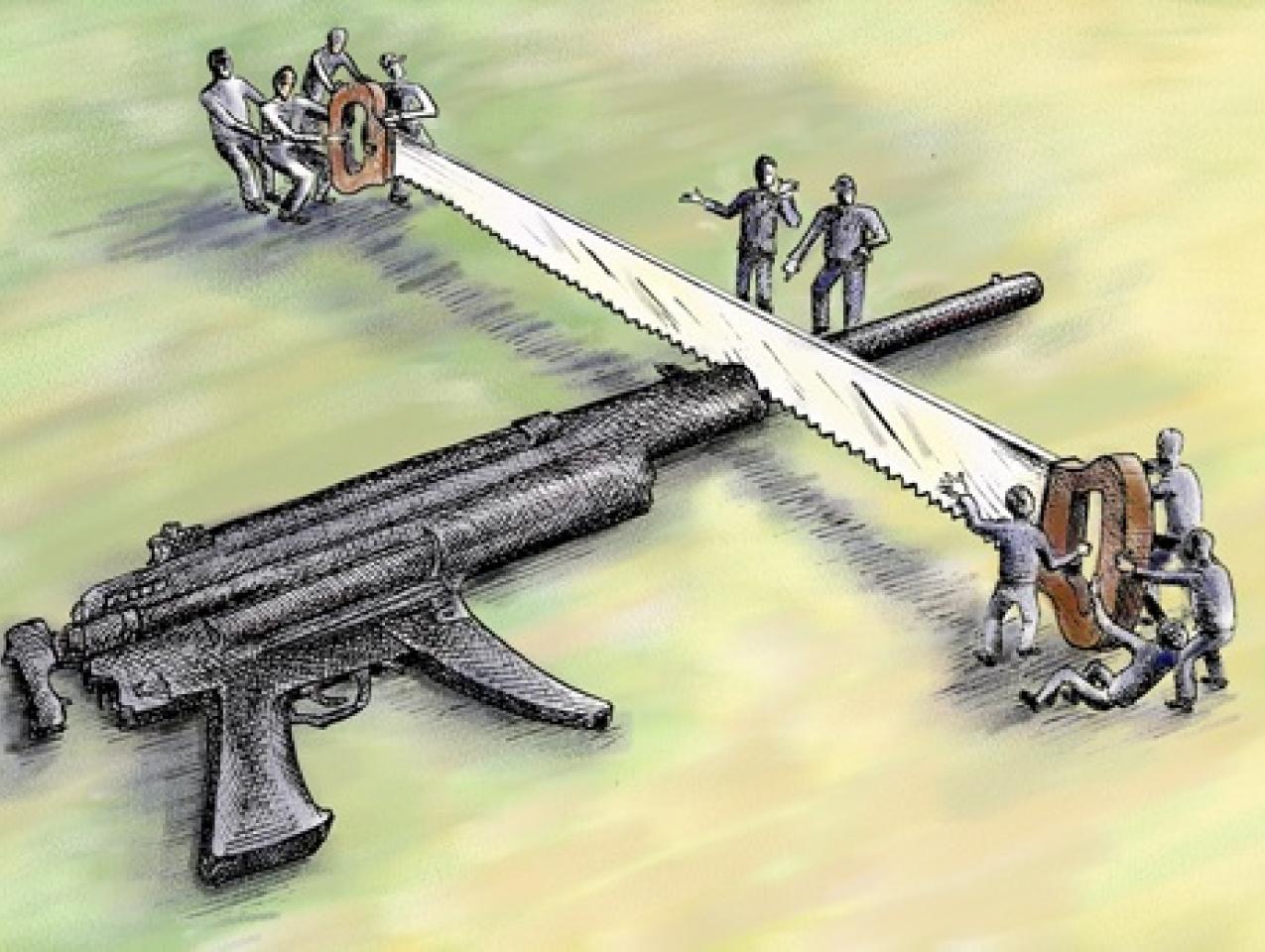

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

Gates, needless to say, was dissatisfied that the goal posts had been moved. This was evident in his January 6 briefing previewing the Fiscal Year 2012 defense budget, where he described any further cuts as "risky at best and potentially calamitous."

This overstates the case, since the FY 2012 budget he outlined actually raises spending for the coming three years, and even with the White House’s new demands only constitutes a 2 percent reduction across the five year time frame of the budget. And that the services could identify $100 billion in their budgets that wasn’t essential, and the civilian side of the Department of Defense another $50 billion, suggests there is yet some slack in the budget.

Still, Gates is not a dramatic man, and that he made such a dramatic statement should give us all pause. Secretary Gates’ dissatisfaction about the cuts, and his effort to draw a clear firebreak against any further cuts, results from the breach of trust he is having to carry out in forcing the services to hand over the savings they produced in their reviews.

As Dwight Eisenhower once said, "farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil and you’re a thousand miles from a cornfield."

The most egregious breach of faith has to do with the size of two of the service branches. Having just finished increasing the size of the Army by 22,000 forces, the department will now reduce it by 27,000. And having just increased the size of the Marine Corps by 22,000 since 2007, it will reduce it by 15,000-20,000. By the way, the military’s forces are still too small to provide soldiers and Marines a year respite between deployments.

It merits mention that no other department of the federal government has identified cost saving measures for their budgets, much less savings of the magnitude that Gates’ Department of Defense did. Spending for the Department of State and Agency for International Development has increased by 155% since 2003, and both departments have just revealed expansive plans for yet more budget spikes.

President Obama is penalizing the Department of Defense for being the only agency of the federal government good enough at its job to actually budget its spending needs out for five years. The Department of Defense is this disciplined for three reasons: first, because the nation cannot simply raise a military when it needs it. The lag time required to recruit soldiers, train them, and procure weapons is too substantial. Second, the defense department buys complex weapons systems with long developmental cycles. And third, the department takes seriously the charge of building congressional confidence in its programs.

Those who advocate large-scale cuts to defense spending have several favorite statistics: defense constitutes half of all discretionary federal spending and our country spent more on defense last year in inflation-adjusted dollars than any year during the Cold War.

These facts are accurate but in isolation give an unbalanced view. Also relevant are that defense spending constitutes less than 4 percent of the federal budget, that the nation is fighting two wars, and that 4 percent is the lowest proportion of GDP spent on defense since 1945. A more accurate context in which to understand defense spending is this: it is high in absolute terms, but it is historically low as a proportion of our economy and low as a cost for what is being undertaken and achieved.

Defense spending is also more productive to the economy than other types of government spending. Harvard economist Martin Feldstein even argued that if the federal government wanted an effective stimulus program, it should funnel more money into defense, because it was primed to spend it well in U.S. companies and on U.S. citizens. Beyond that, the department would eventually need to spend money on refurbishing war materials.

It is often argued on the left that our military spending spurs competitive increases in spending by others—an arms race of sorts. This might be true at the margin—if a country could only gain a small military edge, it could hope to attain a war-winning advantage—but this is a moot point given that American defense spending constitutes more than half of the world’s total. Our defense spending actually serves as a disincentive for friends and enemies alike to beef up their own defense budgets.

Defense spending is at a historic low as a proportion of our economy.

Some people say that our defense spending is far in excess of the genuine threat our nation faces, and that cheaper alternatives that would accomplish our security needs are available. For instance, according to one recent Vanity Fair article titled "Smarter Defense-Spending Could Allow Republicans to Cut $100 Billion from Budget," the Marine Corps should cut the $2.37 billion expeditionary fighting vehicle system, an amphibious landing craft to get Marines ashore. Even when not taken to that risible extreme, arguments to chop individual systems from the budget underestimate the degree of difficulty associated with building a program of defense capabilities that secure this country by balancing risk across many different possibilities and problems.

As Dwight Eisenhower once said, "farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil and you’re a thousand miles from a cornfield."

The Republican leadership is unanimous in saying that defense should not be exempt from cuts. They base their judgment on two rationales. First, in the Department of Defense’s $720 billion budget, which has doubled in the past seven years, there is bound to be some room to save and cut. In fact, there is: the Army recently identified a staffing reduction of more than a thousand people by "eliminating unneeded task forces." Second, if fiscal discipline requires Americans to make dramatic sacrifices, then the government needs to look critically and carefully at all potential sources of revenue that can be cut.

The good news is that none of the spending reduction plans put forward by Republicans feature defense cuts. Representative Paul Ryan’s Roadmap for America does not address defense spending. That’s because non-discretionary spending—what has come to be called "entitlements"—on Social Security and Medicare are driving our national insolvency. Another plan, the Spending Reduction Act of 2011, advocated by Senator Jim DeMint and Representatives Jim Jordan and Scott Garrett, would cut non-security discretionary spending to 2006 levels, while reducing federal spending by $2.5 trillion. This plan also does not incorporate defense cuts.

The Obama administration chose to begin spending cuts with defense. No other agency has identified budget reductions or been forced to hand over internal savings. It is one thing to argue, as Republicans have, for a broad sharing in the sacrifices needed to return this nation to solvency. It is quite another to balance the budget on the backs of the people already making enormous sacrifices for our country.