The importance and potential impact of empowering patients with the decision-making capability and the dollars to make value-conscious health-care decisions cannot be overstated. Recent proposals to restructure the tax code, nationalize insurance markets, and reform the legal system are steps in the right direction. But if a goal of health-care reform is to empower the patient, why is there such a mystery about medical prices? We currently allow the government to set prices—directly or indirectly—for the great majority of medical procedures. Instead, the role of the government should be to make the pricing of these procedures transparent.

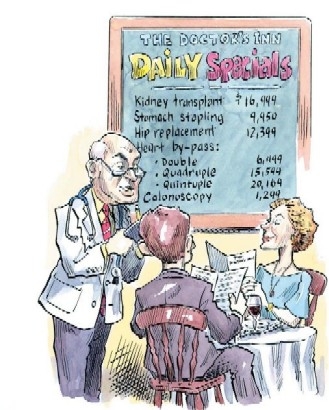

In our current system, few patients are aware of the costs of their medical care, generally because patients have no reason to ask because it is paid for by third-party insurance programs. This has allowed hospitals’ and doctors’ prices to be shielded from public view. Patients, however, would greatly benefit if the government required that prices be posted for common medical procedures before the care is administered, in the same way that the government requires clear labeling of medicine and food and open disclosure of prices on gasoline and automobiles. When prices are openly stated and widely known, competition will ensue and prices will come down—regardless of whether or not patients initially use that knowledge to make their “purchasing” decisions. This would allow the price mechanism to function again.

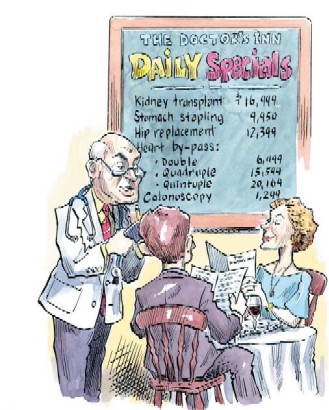

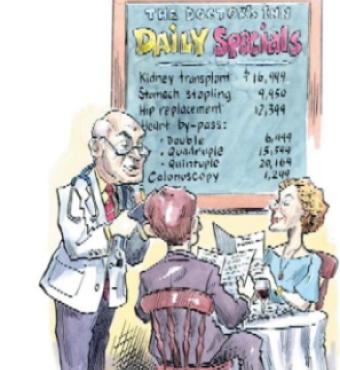

| If a goal of health-care reform is to empower the patient, why is there such a mystery about medical prices? |

Where would the price data come from, and for what procedures should prices be known at the start? I propose to start with the 10 to 20 most common procedures in both outpatient and inpatient medicine, such as MRI scans, a surgeon’s bill for rotator cuff repair, or an anesthesiolo-gist’s bill for a cardiac surgery procedure. Procedure-based prices are more appropriate because diagnosis-based prices would likely be too complicated to calculate and contain too many variables. To preempt the claim that “price depends on individual situations,” posted prices could be based on a retrospective analysis of the provider’s previous three or six months’ average of charges.

How would the price data be posted? The patient needs to know upfront, not after the fact. One way would be at the time when patients are handed the “medical information materials,” such as brochures describing procedures and consent forms. Another way is to post them in the clinic offices and hospital admitting rooms. A third would be to put them on the Internet.

The idea of informed consumers knowing prices and controlling their health-care dollar is extremely powerful. In those few cases where patients have had to pay for procedures out of pocket and have had information about price—for example, whole-body CT screening—the cost did indeed come down, rapidly and dramatically. (The price of whole-body CT procedures declined by more than 75 percent in just a few years!)

Ultimately, no commodity, no service industry, sells to consumers without openly disclosing prices. Doctors and hospitals might be forced to rethink their prices if they knew those prices would become part of the public domain. There should be no mystery to patients about what their health care will cost.