- Economics

- World

- Economic

- History

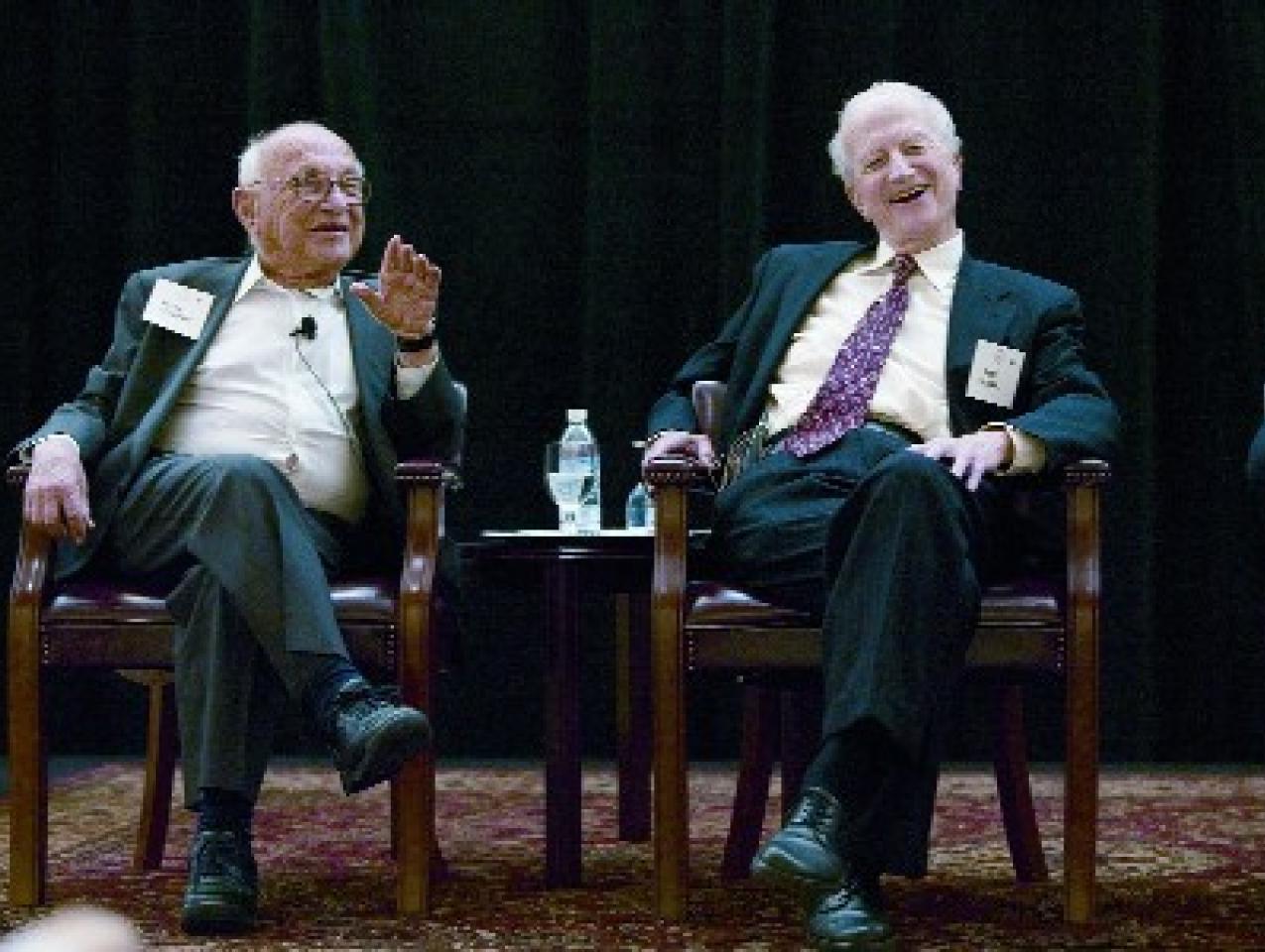

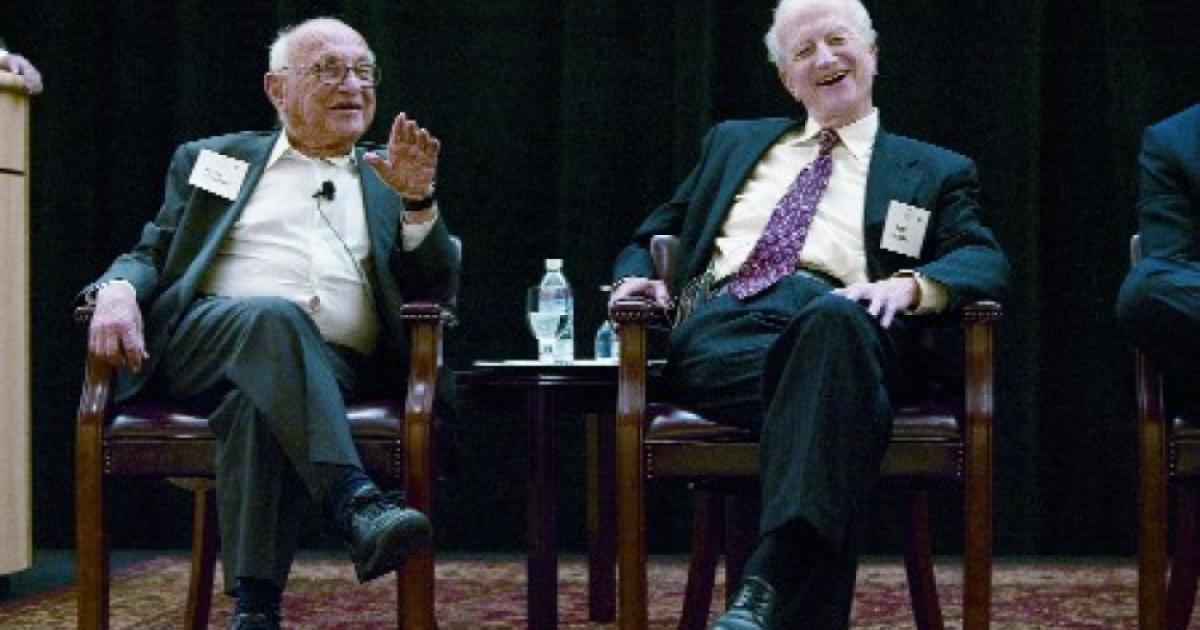

Milton Friedman was the most influential economist of the twentieth century when one combines his contributions to both economic science and public policy. I knew him for many decades, beginning when I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago and then as a colleague, mentor, and very close friend.

I will not dwell here on what a remarkable colleague he was. I do, however, want to describe my first exposure to him as a teacher because he enormously changed my approach to economics and to life itself. After my first class with him a half-century ago, I recognized that I was fortunate to have an extraordinary economist as a teacher. During that class he asked a question, and I shot up my hand and was called on to provide an answer. I still remember what he said, “That is no answer, for you are only restating the question in other words.” I sat down humiliated, but I knew he was right. I decided on my way home after a very stimulating class that despite all the economics I had studied at Princeton, and the two economics articles I was in the process of publishing, I had to relearn economics from the ground up. I sat at Milton’s feet for the next six years—three as an assistant professor at the University of Chicago—learning economics from a fresh perspective. It was the most exciting intellectual period of my life.

In considering his many contributions to economics I will pass over his major innovations in scientific economics. These include his emphasis on permanent income in explaining aggregate consumption and savings, his study of the monetary history of the United States, his explanation of the stagflation of the 1970s, his analysis of the value of a stable and predictable monetary framework to help stabilize the economy, his early contributions to the theory and measurement of human capital, his discussion of choice under uncertainty, and his famous essay on methodology in economics.

Competition and Choice

Milton’s remarkable book Capitalism and Freedom, published in 1962, contains almost all his well-known proposals on how to improve public policy in different fields. Those proposals are based on just two fundamental principles. The first is that, in the vast majority of situations, individuals know their own interests and what is good for them much better than government officials and intellectuals do. The second is that competition among providers of goods and services, including among producers of ideas and seekers of political office, is the most effective way to serve the interests of individuals and families, especially of the poorer members of society.

The famous education voucher proposal found in this book (based on an article he published in the 1950s) embodies both principles: that parents generally know the interests of their children better than teachers unions and school boards do and that competition among schools is the best way to serve the educational interests of children. He added the further insight that one can and should separate government financing of education from government running of schools. The voucher system retains government financing but forces public schools to compete for funds against private for-profit and nonprofit schools. The voucher proposal has won the intellectual battle over the value of competition among schools at the K–12 level as well as at the college level, but so far vouchers have won only limited political victories in terms of actual implementation. This is mainly due to the dedicated opposition of the teachers unions, which fear competition from private schools.

| I sat at Milton’s feet at the University of Chicago for six years—it was the most exciting intellectual period of my life. |

Both individual choice and competition are the foundation of Milton’s 1962 radical proposal to privatize the Social Security system. He argued, correctly in my judgment, that the vast majority of families could be trusted to provide for their retirement if given appropriate incentives and that they should be allowed to invest in retirement funds provided by competitive investment companies. The government-run social security systems then in effect in the United States and all other countries with retirement systems taxed earnings in ways that discouraged effort and encouraged underground activities. These tax receipts were then paid out to retirees according to politically determined criteria. Chile started the first private system of personal accounts modeled along the lines laid out in Capitalism and Freedom and has since been followed to some degree by many other countries, such as Mexico, Singapore, and Great Britain. The United States has tax-free IRAs and Sep savings accounts, but we have not yet implemented privatization of our basic Social Security system, even though an enormous financial deficit on this system will occur in about 15 years unless the system is significantly reformed.

Milton also proposed a flat income tax rate in Capitalism and Freedom, showing that a rate of about 20 percent in the United States could raise the same revenue and in a much simpler and far less costly way than the progressive income tax system in effect in the early 1960s. Further theoretical analysis of what are called optimal tax rates has generally concluded that a flatter tax would be best at combining efficiency with redistribution of income to poorer families. The appeal to Milton of the flat tax was based again on his confidence that individuals react to incentives and that they take steps to further their interests. In this case, he argued that highly progressive taxes induce taxpayers to find and exploit tax loopholes, so that legally, and at times illegally, taxpayers cut their tax payments by hiding income or converting it into other forms. A flat income tax was introduced early on by Hong Kong and has in recent years been followed by many countries, including Russia and eight other Eastern European countries. The United States has significantly flattened its income tax structure since the publication of Capitalism and Freedom, especially as a result of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, although a more progressive structure has been creeping back in since that reform.

| Milton’s public policy proposals are all based on just two fundamental principles: first, individuals know their own interests better than government; second, the free marketplace is the most effective way to serve those interests. |

The volunteer army was not discussed in Capitalism and Freedom, but Milton did propose to replace the military draft in several articles published about the same time as the book. He argued that a volunteer army would attract, at reasonable cost, a dedicated military force of men and women who would volunteer owing to a combination of patriotism and economic opportunities. A volunteer system is especially effective in situations where full-scale mobilization of available manpower is not required. His advocacy of a volunteer army to replace the draft induced President Nixon to put Milton on a committee charged with considering the issue. Many persons on the committee initially opposed the idea, especially General William Westmoreland, head of military operations in Vietnam. However, Milton’s persuasiveness eventually won over the vast majority of the members to his position, and in 1973 the United States changed to a volunteer armed force. Seeing how well this system has operated, few military leaders now want to return to a draft.

| Milton argued that economic freedom promotes political freedom and that political freedom is not likely to persist without economic freedom. |

Milton proposed in Capitalism and Freedom (and in an article in the 1950s) to abolish the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates and move to fully flexible exchange rates. Under a flexible exchange system, rates are determined by the competitive supply and demand for different currencies by individuals and businesses. The prevailing view had been that a system of flexible exchange rates would be unstable, so Milton argued that flexible exchange rates would be not constant but stable—unstable rates implied, he argued, that speculators on the average would lose money, which he did not believe was likely. This view of the behavior of speculators was challenged, but I believe Milton was basically right. In any case, the issue was decisively settled after Nixon took the United States off the gold standard in 1972 and replaced it with a system of flexible rates in 1973. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange, led by Leo Melamed, then saw the opportunity to set up futures markets in currencies, which it did with Milton’s help. These markets were enormously successful and put to rest forever the belief that one could not have an effective system of flexible exchange rates. They provide an opportunity for businesses to hedge their currency risks by trading on currency futures.

Economic and Political Freedom

The first chapter of Capitalism and Freedom considers the link between economic and political freedom. He argues there that economic freedom promotes political freedom and that political freedom is not likely to persist without economic freedom. “The kind of economic organization that provides economic freedom directly, namely, competitive capitalism, also promotes political freedom because it separates economic power from political power and in this way enables the one to offset the other.” Findings since then suggest that although economic freedom can begin under totalitarian regimes, such as under General Pinochet in Chile and General Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan, economic freedom produces economic growth and other changes that usually lead to much greater democracy, as in Taiwan, South Korea, and Chile. The important implication is that China will become more democratic if it continues on its path of greater economic freedom and greater growth.

| Although Milton’s ideas live on stronger than ever, it is hard to believe that he is not here. |

On whether one can have democracy without economic freedom, Milton said, “I know of no example in time or place of a society that has been marked by a large measure of political freedom, and that has not also used something comparable to a free market to organize the bulk of economic activity.” Sweden and other Scandinavian countries have been vibrant democracies, and yet governments in those countries tax away more than half the income. The majority of those taxes, however, are transferred back to individuals in the form of retirement incomes, medical care, and in other ways. Although these countries mainly rely on private enterprise, not government enterprises, to organize their economies, is that enough freedom to qualify as economically free? That depends on the definition of economic freedom, yet I believe Milton was right that thoroughgoing restrictions on economic freedom would turn out to be inconsistent with democracy.

To conclude on a more personal level, I was most impressed by Milton Friedman’s sterling character—he would never soften his views to curry favor—his perennial optimism, his loyalty to those he liked, his love of a good argument without any personal attacks on his opponents, and his courage in the face of prolonged and virulent attacks on him by others. I cannot count the number of times I participated with him in seminars, or how many visits my wife and I shared with Milton and Rose, his wife of almost 70 years. Rose, a fine economist, would not hesitate to differ with her husband when she believed his arguments were wrong or too loose.

When I spoke with Milton on the phone for the last time, he sounded strong and a bit optimistic about his health, even though he had just returned from a one-week hospital stay with a severe illness that a few days later took his life. Although his ideas live on stronger than ever, it is hard to believe that he is not here. I can no longer seek his opinions on my papers, but I will continue to ask myself about my ideas: Would my teacher and dear friend Milton Friedman believe they are any good?