- Economics

- US Labor Market

Sustained high growth in developing economies is a post–World War II phenomenon. Using GDP figures, I take “high” to mean above 7 percent and “sustained” to mean 25 years or more. These cutoffs are arbitrary, but a similar picture emerges with variants. Growth at these rates produces very substantial changes in incomes and wealth: income doubles every decade at 7 percent.

There are 11 such cases of sustained high growth, and eight are in Asia: Botswana, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Malta, Oman, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand. (Per capita income data are somewhat lower because of population growth.) China is the latest case, the largest in terms of population, and the fastest. India is also entering a period of high growth. While it remains to be seen whether growth in these lands will be sustained and for how long, the essential ingredients are being put in place, and the general sense of optimism seems justified.

Growth at these rates is clearly possible, as the cases show. But they should not necessarily be taken as targets or goals. We have no evidence yet that all countries can achieve growth at these rates, even ones at similar stages of development as measured by income levels. What is clear is that meaningfully high growth rates that significantly improve people’s lives and their freedom to be creative are increasingly accessible, and that understanding how they are achieved is of great value to the governments and the leaders of developing countries, as well as to advanced countries, international institutions, and nongovernmental organizations that seek to be supportive.

Key Ingredients of Sustained Growth

Growth in incomes comes from three sources: investment, technology or applied practical knowledge, and increases in the fraction of the population that is productively employed. The last is important in the early stages of growth because drawing labor from traditional sectors, where it is in surplus, to new, more productive employment, is an important driving force.

While each instance of sustained high growth is to some extent idiosyncratic, the cases share certain features. In all cases, there is a functioning market economy with price signals, incentives, decentralization, and enough definition of private property ownership to enable investment. All attempts to circumvent this necessary condition through central planning have met with major misallocations of resources and failure.

The high-growth paths are characterized by high levels of savings and investment, even in the early stages when the per capita incomes were low. (High savings in this context means at or above 25 percent of GDP.) China again was the high-water mark, ranging between 35 percent and 45 percent of GDP. The investment includes a substantial component of public-sector investment in education and infrastructure, both being crucial as they increase the rate of return to private-sector investment, which is the proximate driving force in the growth process.

A third key ingredient is resource mobility. Contrary to the image that sometimes comes from a macroeconomic overview, productivity growth at these rates is not achieved by having everyone do what they were doing before but a little bit more efficiently. The portfolio mix of economic activity changes very rapidly. This is what Joseph Schumpeter called “creative destruction” and Paul Romer calls “churn.”

At company and industry levels, new firms and sectors are created and others decline or die off. If you take a snapshot of a rapidly growing developing economy at five-year intervals, the changes are dramatic. At 15-year intervals the same economy is barely recognizable in the second picture. South Korea is not now a center of labor-intensive manufacturing, but it once was. The same is true of Japan, though one needs to be in an older generation to remember. Even advanced economies like Spain, Ireland, and Italy were at some stage surplus-labor economies; they employed that surplus in labor-intensive industries or exported it or both.

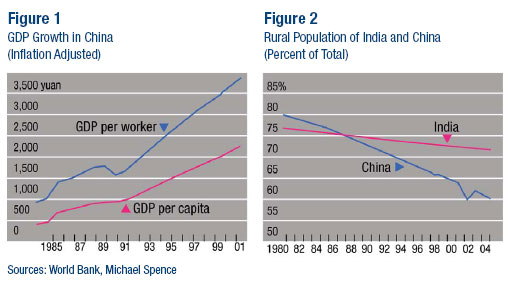

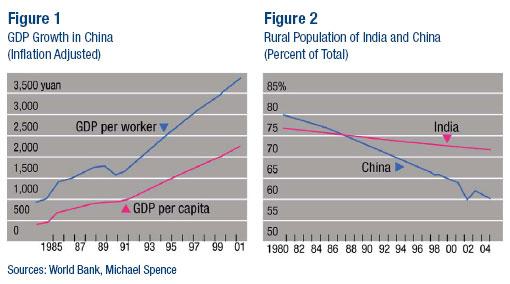

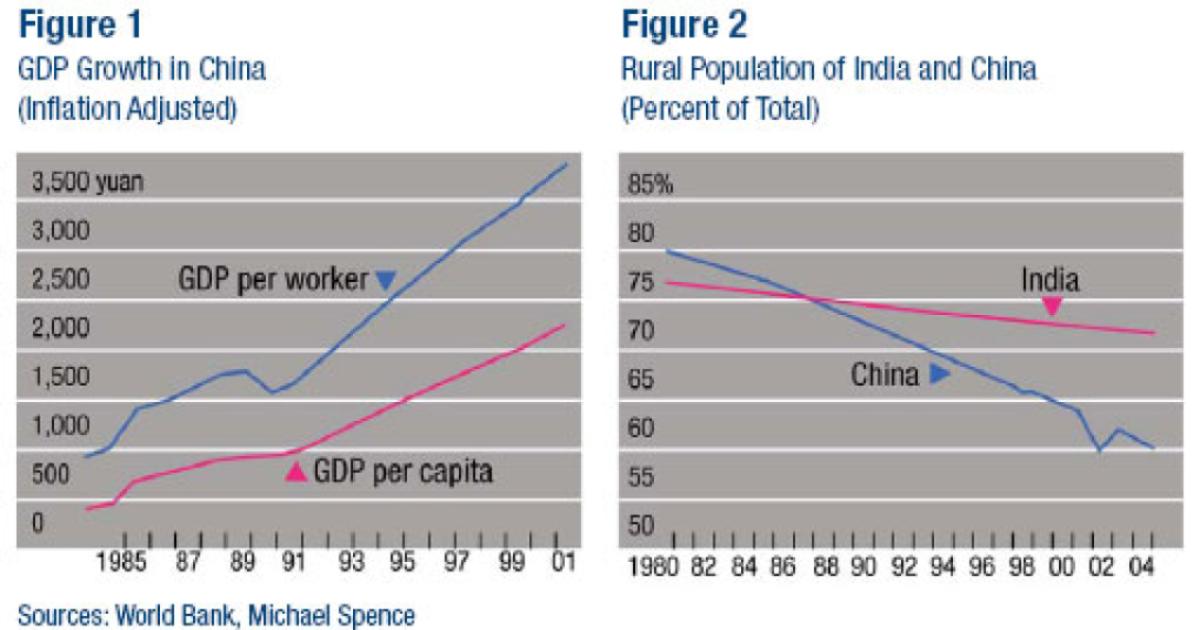

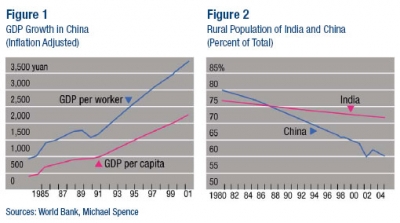

In the early stages of rapid growth, the agricultural sector is usually the location of a vast majority of the people. Typically, labor is underemployed in such traditional sectors, and thus people move to cities and new industrial sectors where investment is taking place and productivity is higher. The loss in output in the traditional sector is minimal or zero because of the surplus labor condition, and hence the overall productivity gain is substantial. See figure 2 for the percentage of the population that is rural in India and China. This movement of people geographically and across sectors is not an ancillary side effect of the growth process but rather the essence of it.

The difference between the growth rate of GDP per capita and GDP per worker in China (figure 1) is very close to the 1 percent per annum decline in the rural population: the movement of people to high-growth and high-productivity sectors that serve the demands of the global economy. It is worth noting that this movement of people is a major challenge in the development process. In the case of China, 1 percent represents 13 million people moving to cities each year, with attendant needs for infrastructure, education, and services.

As people move and productivity rises, it is possible for everyone to be better off. But those who move to new sectors first have higher productivity and higher incomes, resulting in a pronounced tendency for income inequality to rise for an extended period. While this is a natural consequence of the process, it presents a challenge. Excessive inequality of income and wealth is not only a normative problem in most societies; it is also socially and politically disruptive and can threaten the support for the policies and public-sector investments that in part sustain the growth process. As a result, such inequalities need to be mitigated through the redistribution of income or other important services such as health care, education, and pensions, and by ensuring that access to infrastructure (clean water, transportation, power) is reasonably equitable.

Institutions and policies that retard the movement of people and resources will also retard growth, which is true in advanced as well as developing economies. Such policies may nevertheless be justified on the ground of protecting people from the full effect of market forces. But such protections are best if they are transitory, not permanent; generally it is better to protect people and incomes rather than jobs and firms. The latter approach impedes the competitive responses of firms in the private sector and, in the context of the global economy, becomes very expensive.

Probably the most important feature of sustained high growth is that it involves leveraging the demand and resources of the global economy. There are no known exceptions to this principle. All cases of sustained high growth prominently include a growing export sector as a growth driver and a rising fraction of GDP associated with exports and imports. There are no examples of sustained high growth in the postwar period that do not involve integration into the global economy. The systematic reduction of barriers to trade and investment in the past 55 years, and the dramatically falling costs of transportation and information and communications technologies, have combined to raise the level of that integration. It is the combined effect of these trends that has made the global economy an increasingly powerful source of potential growth.

Resources of the Global Economy

With China and India growing at high rates, there has been a dramatic increase in the fraction of the world’s population experiencing the benefits and challenges of rapid growth. A number of common ingredients in the cases of sustained high growth have been observed: a functioning market system, high levels of saving, public- and private-sector investment, resource mobility, and the capacity to accommodate rapid change at the microeconomic level without leaving people excessively exposed to the risks inherent in creative destruction.

But it is the resources of the global economy that stand out as driving forces in sustaining high growth. These come in three parts:

• Demand. In a relatively poor economy, demand is limited and does not necessarily correspond to sectors of comparative advantage. The global economy is huge, in comparison; at the right prices and costs, demand is, for practical purposes, unlimited.

So once the challenge of identifying industries in which the country can acquire a comparative advantage is met, growth in exports will not be constrained by demand, and growth in the economy can occur at a rate determined by the savings and investment rates. Much of that investment in the early stages will go to the export sector, which can grow at rates high enough to pull the rest of the economy along. As we saw in Japan, Korea, Singapore, and now China, the growth of exports can set in motion a process of sustained growth that is transmitted to the whole economy and could not be achieved by relying on domestic demand alone.

These are the dynamic equivalents of the gains from trade for developing countries. Developing economies are small in relation to global demand and hence they can grow and increase share without having the terms of trade turn against them (China being a possible exception because of its size). They are constrained primarily by their capacity to invest, once the growth process is started. They use underutilized or surplus resources, particularly labor, so that the growth in exports does not come at the expense of declines in other sectors. Advanced economies cannot grow at anything like these rates, and the rapidly growing developing economies will eventually slow down.

• Technology. A second resource the global economy provides is know-how. This ranges from engineering and production technology to managerial expertise and knowledge of global markets—and it does not have to be redeveloped domestically from scratch. And, unlike most commodities, when knowledge is transferred from A to B, both have it.

One way for imported technology to travel is by foreign direct investment (FDI). But there are cases—Japan and Korea—in which there was significant technology absorption from the rest of the world and relatively little FDI. Here, foreign education and explicit programs aimed at learning played important roles.

• Investment. A third area in which the global economy supports higher than otherwise attainable growth is investment or, more precisely, through investment beyond the capacity of the domestic economy to save. One component is FDI, typically not a large fraction of total investment (20 percent of overall investment would be typical). But its magnitude understates its importance because of its role in bringing technology, know-how, and access to external markets.

Beyond FDI, it is possible to invest at rates that are higher than domestic savings can provide. But this area is complex and controversial. Financial investments, unlike FDI, can be reversed easily; if reversals are sudden, they can create exchange-rate volatility, collapses in asset values, and failures in the banking system, as seen in the currency crises of the late 1990s. The understanding now is that imperfectly developed or informationally immature capital markets are vulnerable to volatility, and that complete openness and sudden shifts to complete convertibility of the currency may not be wise. Gradualism, experimentation, and pragmatism are better guiding principles.

Substantial inbound capital in excess of savings may raise the value of the local currency and reduce the competitiveness of the nascent export sectors. An elevated level of the domestic currency or volatility will serve as a deterrent to domestic and foreign investment in export sectors.

Some public-sector borrowing to finance public-sector investment makes sense if the developing country’s fiscal system is sufficiently well structured to ensure the future capacity to repay the debt, and if its political system is such that commitments can be kept. The record is not reassuring. The high-growth cases have not involved much investment financed by foreign savings. The current trend is the opposite: toward building up reserves (modest in some cases, and very large in China). This means running surpluses on the current account (goods and services) and deficits on the capital account. That is, domestic savings exceeds investment.

As the high-growth economies become richer, the relative importance of the domestic economy as a driver of growth increases. The critical role of exports remains, but is at its highest early in the process when the domestic economy is small. Take Japan: it lost its growth momentum in the 1990s in part because, at its advanced stage, domestic consumption is a required engine of growth. Beyond the catch-up phase, growth cannot be sustained on a healthy export sector alone.

It is hard to argue with the diagnosis of sustained high growth in the past half-century. But people do question the future applicability to developing economies that are “starting late.”

The argument is that for those countries that are not resource-rich, their principal resource is abundant labor, inexpensive relative to its productive value, and that the natural territory for comparative advantage is in labor-intensive manufacturing or services. For these countries, the argument goes, it is impossible to compete with China and, prospectively, India. One reason is that the size of China and India, and a variety of advantages that go with scale, is insurmountable. Another is that the infrastructure investments make China hypercompetitive and difficult to match. The conclusion is that one needs to wait for China and India to grow, and that at some point their incomes will rise to the point that they no longer invest in labor-intensive sectors. This argument is unlikely to be right. Although China and India are formidable competitors, exchange rates can adjust to increase the competitiveness of the export sectors of new entrants. In addition, while we sometimes talk about labor-intensive industry as if it were one big lump, in reality there are hundreds of niches. Further, multinationals are risk-averse and unlikely to source their supply chains in just one or two countries. Finally, China and India together now account for close to one-fifth of the U.S. economy, and they are becoming an important source of demand for exports of developing countries—so that newcomers have expanding markets in these two rapidly growing economies.

In short, the global economy remains a resource for generating and sustaining high growth in developing countries. China and India, accounting for 40 percent of the world’s population, are in high-growth mode and are pulling much of Asia with them. There have also been recent increases in exports and overall growth in Africa, though some of that is attributable to an upsurge in commodity prices. Latin America, with the notable exception of Chile, has been stalled at lower-middle-income levels but has the human resources and other assets to shift back onto high-growth trajectories.

The prospects for developing countries are, in fact, probably more favorable now than they have been since World War II. International trade is growing faster than global GDP. The benefits of decades of learning with respect to operating global supply chains are accessible. Information and technology continue to lower transactions costs and to be powerful integrating forces. But perhaps even more important, the key players in all this—the leaders in emerging economies who have the responsibility for building policies that support private-sector entrepreneurship and lead to sustained inclusive growth—have a wealth of experience to rely on. No one is in the dark.