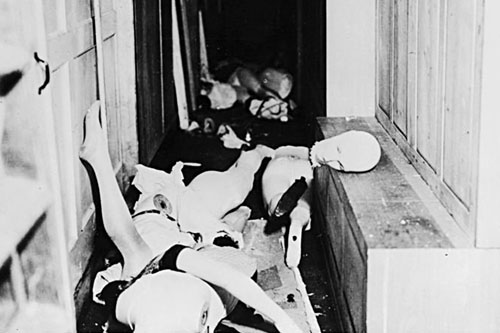

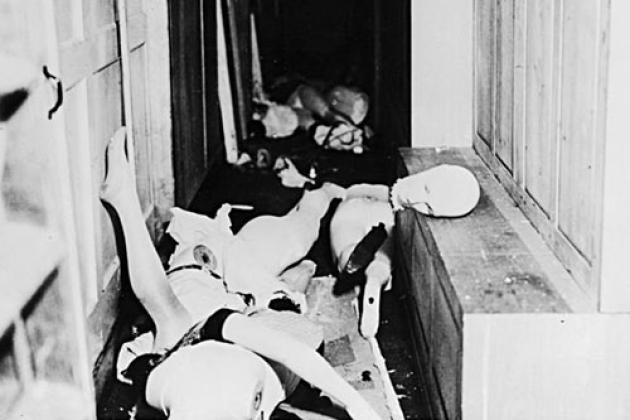

On November 9, 1938, thousands of German storm troopers, acting under direct orders, launched the anti-Jewish pogrom known as Kristallnacht. The attacks left approximately 100 Jews dead and 7,500 Jewish businesses damaged. Hundreds of homes and synagogues were vandalized.

The mastermind of the pogrom, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, explained it to the world as a spontaneous reaction to the murder in Paris of a German diplomat by Herschel Grynszpan, a seventeen-year-old Jew. Goebbels said the pogrom showed the “healthy instincts” of the German people.

Some Jewish organizations, while strongly condemning German actions, expressed concern about the pogrom’s alleged cause. The World Jewish Congress stated that it “deplored the fatal shooting of an official of the German Embassy by a young Polish Jew.” These displays of contrition did not help. Kristallnacht was soon followed by the Holocaust, in which more than six million European Jews died.

What can we learn from that tragic history? First, atrocities on such a scale are rarely spontaneous. They require preparation and organization. Equally important is the lesson that accepting enemy propaganda makes us look weak and shortsighted. Any appreciation of the pretexts for such atrocities makes their perpetrators bolder and more aggressive.

Unfortunately, these lessons have not been learned. In the days after America’s ambassador to Libya and three other diplomatic personnel were killed last fall, when U.S. embassies in Egypt and other Muslim countries were besieged and the American flag burned, the Obama administration and the news media blamed a video clip instead of denouncing the perpetrators.

The lack of realism was stunning. “We reject all efforts to denigrate the religious beliefs of others,” said President Obama—focusing not on the persecution of Christians and Jews in Muslim countries but on an amateur film on YouTube. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called the film “disgusting and reprehensible.” These sentiments were echoed by the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, and a multitude of pundits.

Yet soon it became clear that the events of September 11, 2012, were not a “spontaneous reaction” to the fourteen-minute trailer but were organized—not only in Benghazi, where the Americans were killed, but in Cairo as well. The film, Innocence of Muslims, had been available on YouTube for a long time without attracting any attention. Two days before the riots, it was broadcast in Arabic on the Salafi Egyptian television channel Al-Nas. Several popular preachers on other conservative Islamic satellite channels called upon people to turn out at the U.S. Embassy in Egypt. If this was not organization, what was it?

Still, America’s leaders effectively accepted that the main blame for the embassy attacks should be put on the producers of the video clip, not the organizers of the violence and the participants. Far from standing up for freedom of speech, American leaders practically apologized for the lack of censorship in the United States.

“The U.S. government had absolutely nothing to do with this video,” said Clinton, who clearly did not understand that for those brought up in the world of Islamist propaganda, any attempt to distance the American government from the film could only feed suspicions that the United States was responsible for its production.

These were not merely rhetorical errors. In an ideological war, each such error represents a lost battle.

It is not surprising that America’s leaders are not proficient in the strategies and tactics of ideological warfare. Lessons learned from communism are now long forgotten, and are certainly not taught to current politicians. Still, U.S. leaders could have made fewer mistakes had they adhered to basic principles of American society that require respect for the right of any person to practice his religion peacefully—but not necessarily respect for that religion itself.

I know that difference from personal experience. In the Soviet Union, I fought together with my fellow dissidents for religious freedom. Believers appreciated our support and never asked us to express any allegiance to their faith. Most of us dissidents were not religious people ourselves, but we risked our freedom to stand up for the right to worship. We did it because we believed that religious freedom is a fundamental human right.

The president of the United States, too, should stand for religious freedom. But he does not have an obligation to respect Islam or any other religion. America’s constitutional separation of church and state obliges its leaders to avoid publicly endorsing any particular religion even to the extent of expressing “respect” for it. Similarly, they are enjoined from crusading against blasphemy.

It is important to remember that a war with a fanatical foe is first of all an ideological war, and in such a war, appeasement doesn’t work. There are no defensive strategies. Any attempt to prove that you are right is a defeat. Any suggestion of compromise or acceptance of the legitimacy of your enemy’s ideology is a sign of your weakness—which only provokes further attacks.

An ideological war cannot be won by drones. The winning formula against Soviet communism proved to be peace through strength. A strong military and economy are important, but even more important is standing strong for basic principles. Ronald Reagan, Pope John Paul II, and the Soviet and East European dissidents all understood this.

It is vain to hope that we can completely avoid ideological confrontation by taking more moderate and accommodating positions. We did not start wars with communism, Nazism, or Islamism. They were imposed upon us. Those ideologies thrive on confrontation with the free world. Today we must revisit Kristallnacht, the Holocaust, and the Cold War to recollect our successful experience of dealing with those virulent ideologies.