- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Military

- World

- History

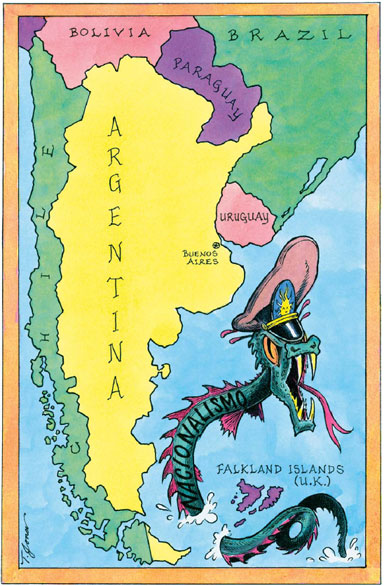

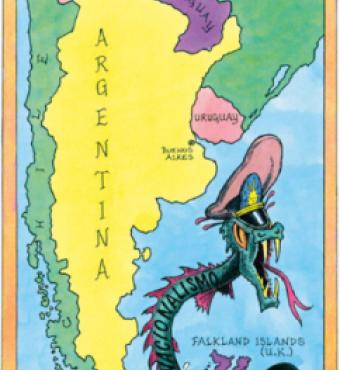

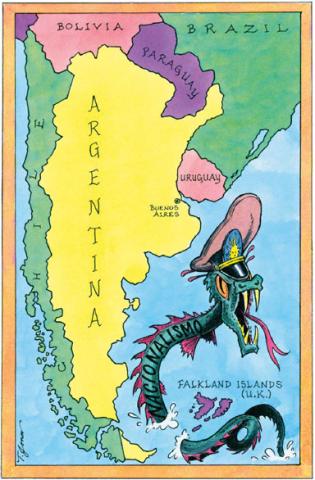

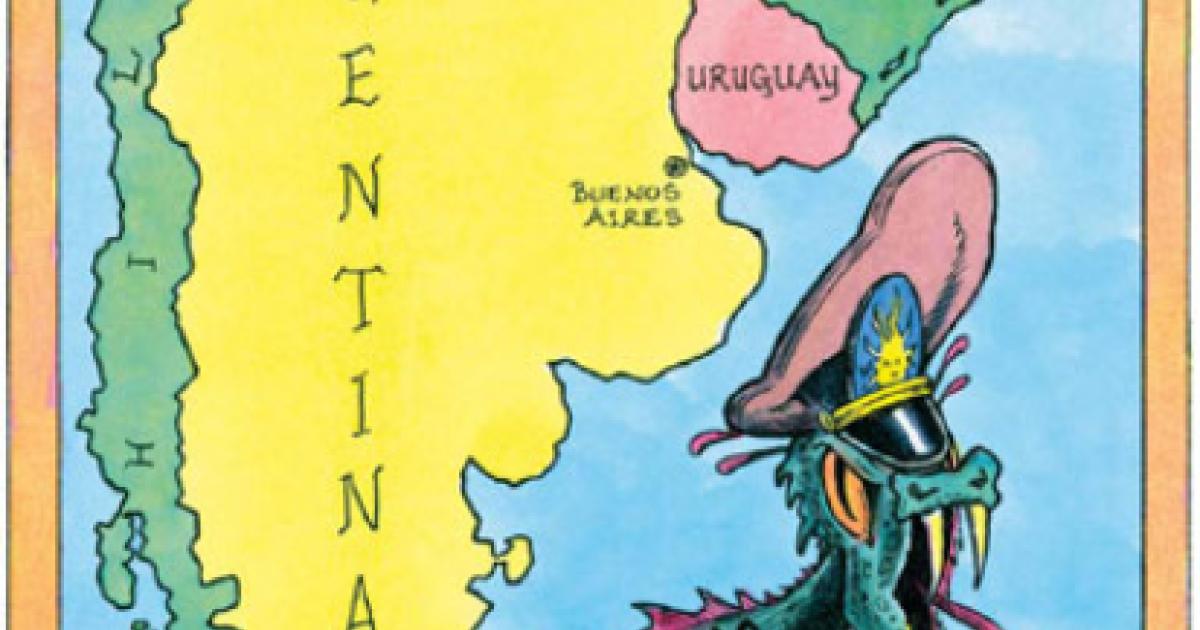

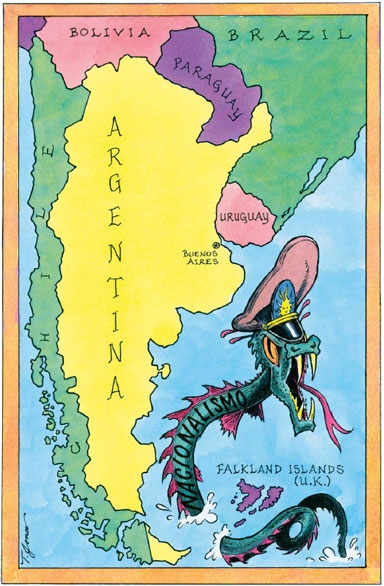

A quarter-century ago, two nations a third of the world apart ended one of history’s most foolish little wars in one of the most isolated regions of the planet. Argentina’s April 1982 invasion of the Falkland Islands (which Argentines call the Malvinas) was routed in ten weeks by British forces. At the time, the launching of a British fleet to engage Argentines in the South Atlantic seemed almost the stuff of a comic opera by Gilbert and Sullivan. But it was no joke: more than 900 died, two-thirds of them Argentines, and some 350 Argentine veterans reportedly have committed suicide since 1982. Argentina planted 18,000 land mines in the islands. Only 10 percent of the mines had been removed when injuries and difficult clearance conditions caused the government to simply mark and fence off the remaining minefields, including part of a downtown street.

For the past 174 years the Falklands complex, which consists of two large and many small islands, has been an overseas territory of the United Kingdom. The British have controlled the islands since 1833, the year a 24-year old Charles Darwin disembarked from HMS Beagle to discover the giant ground sloth fossil, ride and feast with the gauchos, and meet with General Juan Manuel de Rosas, the famous caudillo of the day.

Argentina alone persists in demanding a complete reversal of the 174- year-old status quo, so I conclude that one must look there for the main agitating factors. A high-level Argentine intelligence official who opposes the Malvinas campaign once remarked to me, only partly in jest, that the Malvinas claim cannot be dropped because it is the only thing besides soccer that most Argentines can agree on. Some Argentines passionately insist that they are the ultimate defenders of the rule of law in a world being overrun by Anglocentric pragmatists like me, who stands accused (in a published letter by an Argentine diplomat) of favoring “the forcible dispossession of territories that belong to others.” Thus probably the most one can hope for today is a menos mal (least bad) compromise. But even that would be a great leap forward.

For more than four decades the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization has called for negotiations between the United Kingdom and Argentina, but on terms that assume a British capitulation. This is a non-starter. What is needed is to replace legal grandstanding with Gilbert’s suggestion in Iolanthe to turn “the hose of common sense,” and an objective interpretation of the law, on this dispute.

Of course, the silver anniversary of the war was a time for all involved to solemnly mourn their dead and proudly thump their chests. In mid-June, Prince Charles, then–prime minister Tony Blair, and Margaret Thatcher, who was prime minister during the 1982 war and launched the fleet, joined thousands of British veterans and military leaders at Buckingham Palace for a commemorative service as dozens of military aircraft screeched overhead. Meanwhile, Argentine Vice President Daniel Scioli, speaking at a rally in Ushuaia, the southernmost city in the world, focused on the recovery theme: “The Malvinas are Argentine. They always were; they always will be.” A war memorial in that city praises “the people of Ushuaia who, with their blood, irrigated the roots of our sovereignty over the Malvinas. We will return!”

ARGENTINA STATES ITS CASE

Argentina bases its demand for sovereignty on four points: Spanish colonial claims inherited at independence in 1816; brief and partial post-independence occupation until 1833; the “transient” quality of the Falklands’ population; and the islands’ proximity to Argentina (about 350 miles). The problem has become more urgent in recent years because it is probable that substantial hydrocarbon fields lie offshore. Recent British exploration has suggested that these oil reserves may be equal to those of the North Sea decades ago. Argentina and Britain signed an agreement in 1995 intended to cover fossil fuels, but cooperation has lapsed in the face of charges and countercharges from both sides.

The early history of the Falkland Islands is a string of real and alleged sightings, claims, occupations, and forcible ejections, with several nations periodically competing to claim and control all or parts of the islands. All these were everyday activities of the Western colonial powers during their centuries of ascendancy worldwide. Still, on balance, up to the decisive British occupation in 1833, the islands were mostly under the flags of Spanish and then Argentine authorities, and this is the strongest part of the Argentine case. But this is not enough, despite Argentina’s claims to be the watchdog of international law.

Argentina vehemently rejects the argument that Britain’s violent seizure of the islands—it was actually an American warship that largely disrupted the Argentine settlement—can be made acceptable by the passage of time. But while in the best of all possible worlds we might agree that time does not validate violence, we accept such outcomes all the time. That is how Argentina got its independence from Spain, for instance, as did the United States from Britain, and most of the countries of the United Nations from someone in their past. The process of prescription, the right derived from long-term possession and occupation, is accepted constantly in the real world. After 174 years of continuous and peaceful British administration of the Falkland Islands, this and other arguments overwhelmingly outweigh Argentina’s somewhat stronger formal legal claim dating to the early nineteenth century.

The Argentines and their supporters in the United Nations are out of touch with reality, or simply blinded by ideology, with respect to the right of self-determination. Search throughout history, and it would be hard to find a group of people anywhere more eligible for self-determination than the Falklanders in their contest with the Argentines. In contrast to the Argentines who claim sovereignty over them, they speak English and are almost all of English and Scottish origin. They overwhelmingly oppose being part of Argentina because it is a culture distinct in religion, institutions, and almost every other way. In contrast to the constant and peaceful administration of the Falklands, Argentina’s history has often been violent and unpredictable. In the past fifty years alone, while the Falklands have had harmonious rule, Argentine history has turned up thuggish military dictators and unevenly effective, demagogic democratic leaders; waves of Trotskyist and Peronist terrorists; a nasty retaliatory “dirty war” that left perhaps 30,000 killed, tortured to death, and missing; the unprovoked invasion of the Falklands; within a single decade inflation of some 5,000 percent, a recovery, and an economic collapse that brought the largest debt default in history; and a 2001–02 tango of presidents that saw such a rapid leadership turnover in such a short time that it is hard to remember who they were.

DISTINCT CIVI LIZATIONS

The most disingenuous Argentine claim of all is that after 174 consecutive years the Falklanders are a “temporary population.” Buenos Aires made this argument in 1964 before the U.N. decolonization committee, and it was repeated before the committee in June 2007 by Foreign Minister Jorge Enrique Taiana, who said that “to grant self-determination to the British inhabitants of the islands would imply acceptance of the disruption of Argentina’s territorial integrity.” (As Grenada’s representative on the decolonization committee pointed out in June, “Sovereignty issues [are] overshadowing that body’s sole purpose,” which is to guarantee self-determination.) In 2006, Taiana asserted that the right to self-determination is “not applicable to the islanders, since they were a British population transplanted with the intention of setting up a colony.” How can anyone make such an argument? Argentine officials must know that that is precisely how their country was formed: Spain transplanted Spaniards to establish a Spanish colony, the very colony the “Argentines” overthrew by armed force about twenty years before the Falkland Islands were seized by force. Argentina is now recognized under the process of prescription—why not the Falklands?

In fact, a higher percentage of Argentine families than Falkland Islanders might legitimately be called transients. This results from Argentina’s government- initiated immigration (“to govern is to populate,” one of its nineteenth- century presidents stated) launched just over a century ago. Argentina’s greatest writer, Jorge Luis Borges, concluded that for many reasons Argentines are more “inhabitants” of the land than “citizens.” Nobel laureate V. S. Naipaul described Argentina as “a land of plunder,” almost exactly as Borges had before him. Argentina’s leading comic, Enrique Pinti, in one of his brilliant one-liner political analyses, remarked that Argentines still think of themselves as only “passing through” the country.

The Falklanders did begin their island existence after what amounted to a “shootout” in 1833, but those were the rules of the game in that period of Western colonialism worldwide, from Singapore to Stanley, the Falklands capital. In city after city, region after region, one colonial power violently seized what was occupied by another colonial power or indigenous group.

The Argentines in fact went farther down this road than the Falklanders, for they deliberately killed most of their indigenous population, as American settlers did in the United States. In 2006, the U.N. decolonization committee repeated Taiana’s claim that “the native island population [of the Falkland Islands] had been forcibly removed. . . and replaced by subjects of the occupying power.” But this is nonsense. There was no native population in the Falklands to be killed or ejected. In this light, Falklanders appear to be more legitimate inhabitants of the islands than Argentines do of the mainland.

A study presented to the “First International Conference on the Right to Self-Determination” in 2000 noted that the United Nations recognizes a basis for self-determination in “a history of independence or self-rule in an identifiable territory, a distinct culture, and a will and capability to regain self-governance.” That is the Falklands. The study’s author, Karen Parker, a lawyer who specializes in international law, noted the lamentable fact that often “the principle of self-determination has been reduced to a weapon of political rhetoric.” That is Argentina.

In the end, both Argentina and the Falkland Islands were settled during very long periods by two distinct European civilizations; as a Falklands representative told the U.N. decolonization committee in June, Argentina’s effort to take over the islands is itself the action of a would-be “colonial” power.

A RECIPE FOR CHAOS

After I wrote about this matter in the International Herald Tribune in July, the Argentine Foreign Ministry’s general director of South Atlantic affairs, Eduardo Airaldi, said my defense of prescription in the real world would “strengthen the arguments of those who seek to violate international law and peaceful coexistence.” But he had it backward; if the Argentine approach were adopted as standard international practice, it would lead to a global Pandora’s Box of chaos. Argentina argues that any country that wants to regain territory it lost a couple of centuries ago, which it has claimed however ineffectively since that loss, has the right to its restoration no matter what has occurred in the interim. On these terms, many United Nations member states would become prey to self-aggrandizing neighbors. Perhaps Americans should welcome the Argentine argument for its ability to solve our current immigration problem: we would no longer fret over the presence of so many Mexican immigrants because much of the American Southwest and West, which we took after violent conflict, would be reabsorbed by Mexico.

Let’s also take a brief look at the proximity argument, which seeks to buttress the claim to sovereignty over a neighboring yet totally different offshore civilization. Consider the consequence of numerous countries claiming sovereignty over islands 350 or fewer miles offshore, no matter how distinct the islands’ cultures or how long they had been independent. Cuba could go to the United States, as some Americans wanted in the past— unless, of course, it went back to Spain, which controlled it for some five centuries. The United Kingdom itself might again become part of France, for if one can turn the clock back two centuries, no matter what has happened in the meantime, why not five hundred years, or a thousand?

Much of the underlying problem is that Argentina’s claim, which was somewhat more defensible a century ago, before so much time had passed, has become a carefully cultivated psychological dogma incorporated into the national constitution and school curriculum. Many otherwise serious Argentines endorse this dogma but cannot convincingly defend it, since even an Argentine Clarence Darrow could not dig up convincing arguments or documentation.

WHERE TO LOOK FOR A SOLUTION

Argentina’s foremost newspaper, La Nación, published a version of my argument in July. Official responses have been hostile, yet I have been impressed by how many Argentines all over the world have contacted me to express their agreement. Former foreign minister Andrés Cisneros, who responded to me with his own op-ed in La Nación, repeated some of the Argentine dogma but adopted a conciliatory tone with respect to finding a “realistic” solution, though the devil may still be in the details. He deemed a resolution “not impossible” if wise leaders can be found in both countries to pull it off.

In my judgment, a potentially lasting resolution requires a simple formula that both pacifies, or at least isolates, extreme nationalists and credibly promises tangible and ongoing mutual benefits. At a minimum, Britain could recognize (without acceding to) the Argentine claim, and then all parties could agree to another 175-year cooling-off period. Perhaps, if impartiality can be assured, this could have U.N. oversight. Or London, Buenos Aires, and Stanley could adapt portions of a 1982 proposal of Peru’s then-president, Fernando Belaúnde Terry: the flags of the United Kingdom, Argentina, the Falklands, and the United Nations could fly together over the islands. This could include strong international safeguards to prevent any Argentine political, military, or other interference in the lives of Falklanders or administration of the islands. The Falklanders themselves must agree to the scheme.

A constructive agreement, which seemed much more likely in the 1990s than today, would enable the British, Argentines, and islanders to focus on long-term cooperation in developing fishing, energy, and other projects, with rich rewards for all involved. Recent agreements between Australia and Indonesia contain useful examples of what can be done if the will is there.

But where are the wise leaders Cisneros and I would like to see? I am as skeptical as he is about finding them, particularly on the Argentine side. Ironically, today’s strongly nationalistic President Néstor Kirchner—or his wife, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, if she is elected his successor late this year—would be a fitting Argentine leader to work this out and convince the Argentine people of the virtues of compromise. Few would accuse them of treason, except perhaps Venezuela’s militant President Hugo Chávez, whose stock is now regrettably high in Argentina’s presidential palace. But would either of the Kirchners have the wisdom, courage, and integrity to do it? I doubt it. Is there another viable candidate who would?

Thus the Falkland Islands dispute may continue indefinitely, raising the possibility of another conflict, though Argentines have sworn off war for now. Failure to resolve the conflict will at any rate prevent or hopelessly complicate the long-term cooperation that would benefit Argentines and all others for generations to come.