- Economics

- Contemporary

- World

- International Affairs

- History

Elections around Europe since the onset of the global recession have punished incumbent governments and shown increased support for parties of the far left and far right, ranging from France’s National Front to Greece’s Syriza Party. Responding to such challenges, in some countries establishment parties have visibly moved away from the political center. The leaders of Britain’s Labour Party and France’s Socialist Party have moved to the left; in Hungary, Fidesz has moved to the right.

Accompanying these political shifts has been a redistribution of prestige. While the gloss has faded from the American and European varieties of capitalism, that of China has shone more brightly. In the eyes of many, the backdrop of a global recession has made big government and even “authoritarian chic” look attractive.

In this setting, a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research by Alan de Bromhead, Barry Eichengreen, and Kevin O’Rourke titled “Right-wing Political Extremism in the Great Depression” is timely. The authors show that the rise of right-wing extremism in the Great Depression was not just a German phenomenon. They define extremist parties as those that campaigned to change not just policy but the system of government. They look at 171 elections in twenty-eight countries spread across Europe, the Americas, and Australasia between 1919 and 1939. They find that a swing to right-wing “anti-system” parties was more likely where the depression was more prolonged, where there was a shorter history of democracy, and where fascist parties were already represented in the national parliament. In short, the authors conclude, the Depression was “good for fascists.”

FALSE SOLUTIONS, REAL HARM

In today’s Europe there is no immediate threat of takeover by the far right or far left, and there is no majority for replacing electoral democracy by authoritarian rule. But even established parties are responding to the protest vote in their own countries by conceding populist “solutions” to problems of economic weakness that will weaken markets further by increasing government regulation and raising entitlement spending and tax rates.

Where does the protest vote come from? There is anger and pessimism. There is a search for alternatives to free-market capitalism and representative democracy. The problem is that all the alternatives are worse.

How do we know that all the alternatives are worse? We know it from history.

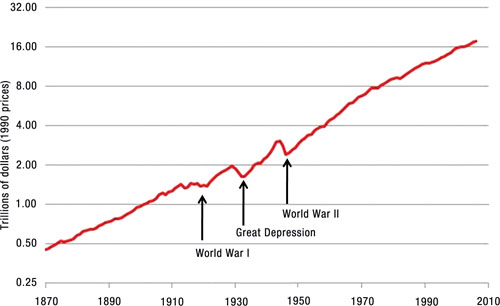

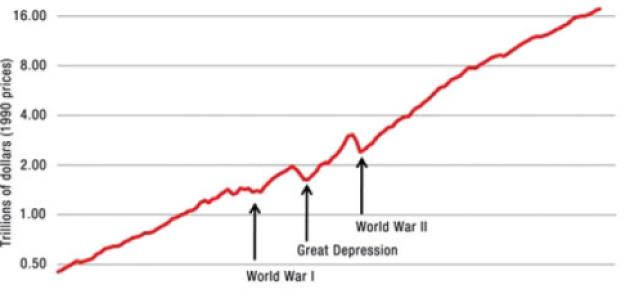

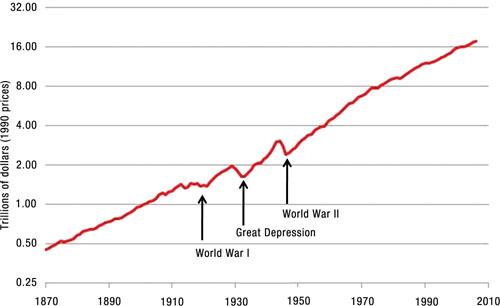

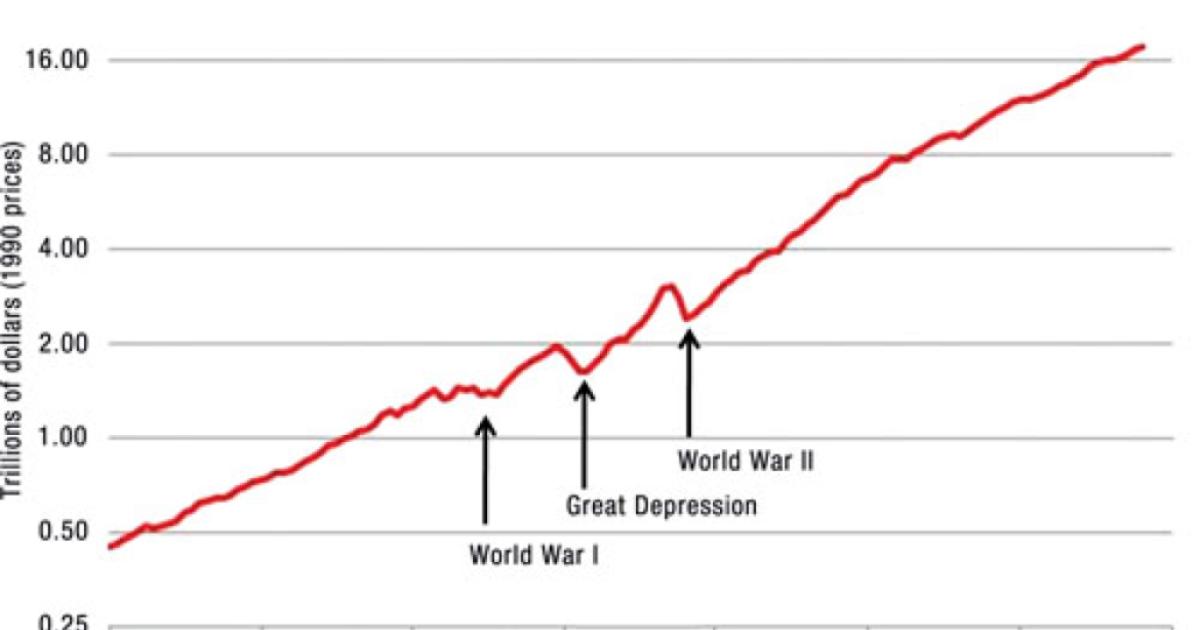

Figure 1 (next page) shows the total real GDPs of sixteen major market economies from 1870 to 2008 (the countries are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States; the data are by the late Angus Maddison). The vertical scale is logarithmic, so the slope of the line measures its rate of growth.

Two things are obvious. One is the steadiness of economic growth in the West over 140 years up to the recent financial crisis. The other is that two world wars and the Great Depression were no more than temporary deviations. They are just blips in the data. For many people they were hell to live through (and the ones who survived these episodes were the lucky ones), but in the long run the economic consequences went away. In fact, recent work by economic historian Alexander J. Field has shown that the depressed 1930s were technologically the most dynamic period of American history.

Figure 1 Economic Growth in Sixteen Major Market Economies

DANGEROUS DIGRESSIONS

One conclusion might be that the economic consequences of the current recession are not the ones that we should fear most. I don’t mean that the economic losses arising from reduced incomes and unemployment are trivial; life today is unexpectedly hard for millions of people, young and old. Young people, even if they will not be a “lost” generation, will suffer and be scarred by the experience. If you’re old enough, you could be dead before better times come round again. At the same time, the kind of pessimism that says that our children will never be as well off as we were is groundless. Although far from trivial, the economic losses associated with the recession will eventually evaporate, just as the economic losses of the Great Depression went away in the long run.

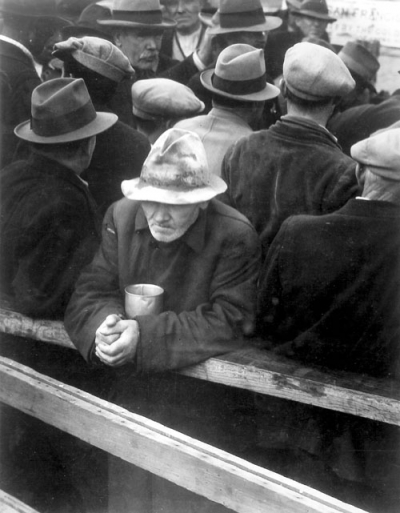

In this iconic image, men line up for bread in San Francisco in the winter of 1933–34. Around the world, the effects of the Great Depression on politics were deep and persistent. As in the 1930s, the backdrop of today’s global slump has made big government and even “authoritarian chic” look attractive again.

We should be more afraid of the lasting political consequences. The effects of the Great Depression on politics were very deep and very persistent. World War I ended with the breakup of the German, Austro-Hungarian, Romanov, and Ottoman Empires. In the 1920s, most of the new countries that were formed became democracies. Then we had the Great Depression, and across Europe there was anger, pessimism, and a search for alternatives to free-market capitalism and representative democracy. By the end of the 1930s, Europe had recovered economically from the Depression but most of the new democracies had fallen under dictators. That led to World War II, in which as many as sixty million people were killed. Fascism was defeated, but then Europe was divided by communism and that led to the Cold War.

Not until 1989 did the average of democracy scores of European countries (measured from the Polity IV database) return to the previous high point, which was in 1919.

In short, the Great Depression stimulated a search for alternatives to liberal capitalism. This search was extremely costly and completely pointless. For a while in various quarters there was admiration for Hitler, Mussolini, or Stalin, their great public works, their capacity to inspire and to mobilize, and their rebuilding of their nations. But both fascism and communism turned out to be terrible mistakes.

Memories are short. Today’s politicians want your vote. And many voters want to hear that some radical politician or authority figure has a quick fix for capitalism. It seems as if we may have to learn from our mistakes all over again. Let’s hope that the lesson is less costly this time round.