- Education

- K-12

- State & Local

- Congress

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

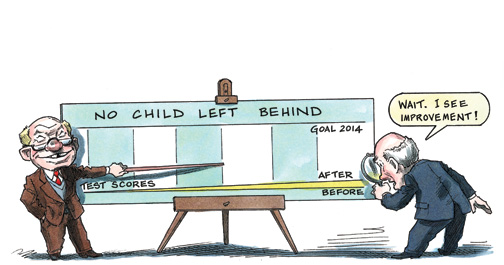

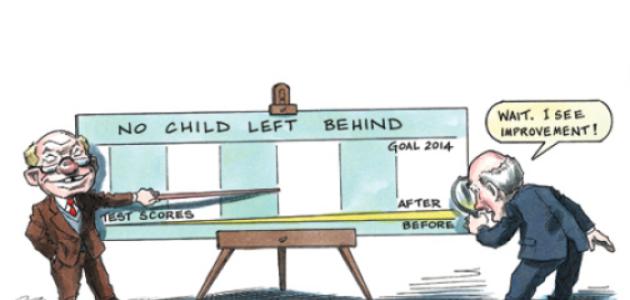

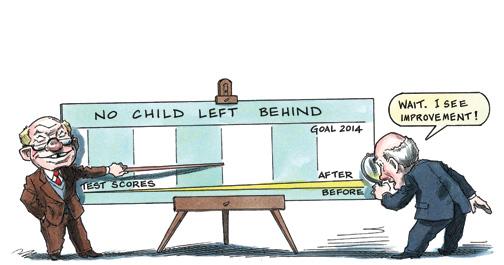

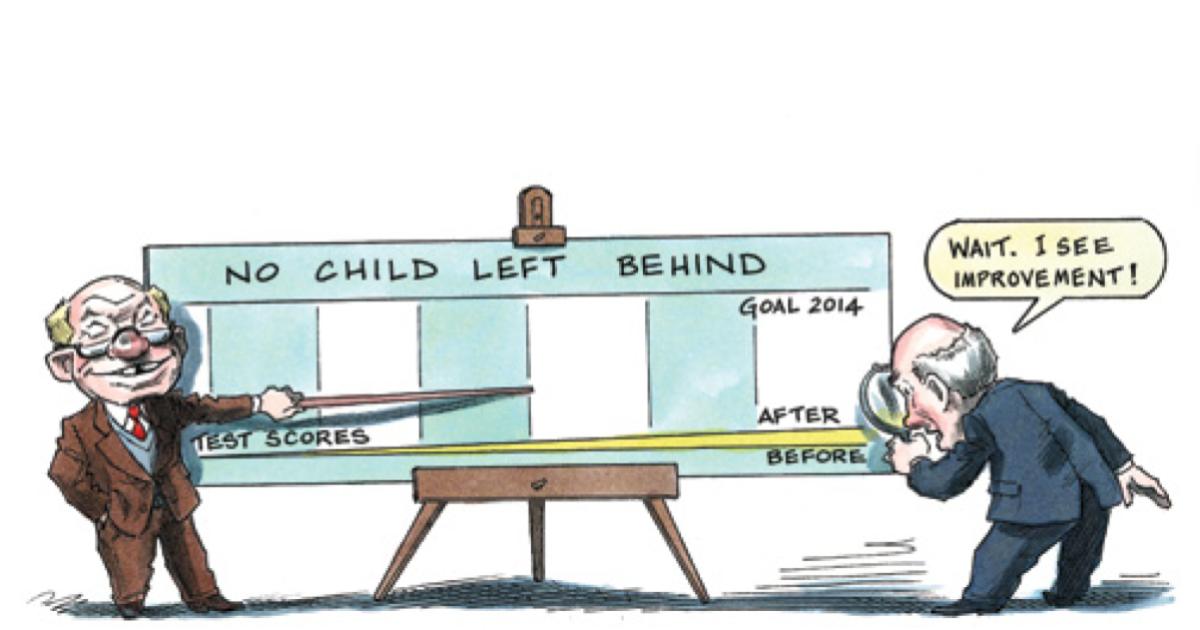

Despite the rosy claims of the Bush administration, the No Child Left Behind Act is fundamentally flawed. National tests released in September show that academic gains since 2003 have been modest, less even than those posted in the years before the law was put into place. In eighth-grade reading, there have been no gains at all since 1998.

The main goal of the law—that all children in the United States be proficient in reading and mathematics by 2014—is simply unattainable. The primary strategy—to test all children in those subjects in grades three through eight every year—has unleashed an unhealthy obsession with standardized testing that has reduced the time available for teaching other important subjects. Furthermore, the law completely fractures the traditional limits on federal interference in the operation of local schools.

Unfortunately, congressional leaders in both parties seem determined to renew the law, probably after the presidential election, with only minor changes. But No Child Left Behind should be radically overhauled, not just tweaked.

Under the law, the states devise their own standards and their own tests. On the basis of test results, every school is expected to make “adequate yearly progress” in grades three to eight so as to meet that goal of universal proficiency by 2014. Schools that do not meet their annual target for every group of students—as defined by race, poverty, language, and disability status— are subject to increasingly onerous sanctions written into the federal law.

Schools that fail to meet their target for two consecutive years must offer their students the choice of attending a more successful public school; schools that fail the following year must provide tutoring to their students. If the students continue to miss their target, the entire teaching and administration staff may be replaced, the school may be turned over to state control, or it may be converted into a charter school.

Yet these tough sanctions have thus far been ineffective. Federal agencies report that only 1 percent of eligible students take advantage of switching schools and that fewer than 20 percent of eligible pupils receive extra tutoring.

In the inner cities, where academic performance is weakest, only a handful of students move to successful schools because there are few seats available. In rural America, choice is limited by the small number of schools in those geographic areas. Furthermore, neither research nor experience validates any of the “remedies” written into the law. There is little evidence that failing schools improve if they are turned over to state control or converted to charter status.

No Child Left Behind can, however, be salvaged. Policy makers must recognize that they need to reverse the roles of the federal government and the states. Each level of government should do what it does best. The federal government is good at collecting and disseminating information, whereas the states and school districts—being closer to the schools, teachers, and parents than the federal government—are more likely to be flexible and pragmatic about designing reforms to meet the needs of particular schools.

Washington should supply unbiased information about student academic performance to states and local districts. It should then be the responsibility of states and local districts to improve performance.

Current law pressures state education departments to show that schools and students are making steady progress even when they are not. Thus the results of annual state tests are almost everywhere better than the results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the benchmark federal test that is administered every other year.

Many states claim that 80 percent or more of their students are proficient in reading or math; at the same time, the federal assessment shows only a minority of students in those states reaching its standard of proficiency. We will never know how well or poorly our students are doing until we have a consistent national testing program in which officials have no vested interest in claiming victory.

Moreover, Congress now decides precisely which sanctions and penalties are needed to reform schools, which is a task far beyond its competence. The leaders of the House and Senate Education Committees are fine people, but they do not know how to fix the nation’s schools.

Congress should also drop the absurd goal of achieving universal proficiency by 2014. Given that no nation, no state, and no school district has ever reached 100 percent math and reading proficiency for all grades, that goal cannot be met. Perpetuating this unrealistic ideal only guarantees that increasing numbers of schools will “fail” as the magic year 2014 gets closer.

Unless we set realistic goals for our schools and adopt realistic means of achieving them, we run the risk of seriously damaging public education and leaving almost all children behind.