- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- US Labor Market

- Education

- Economic

- Contemporary

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

In one of the first economic-liberty cases I argued, the judge lamented that the oppressive regulatory barriers that my client faced sounded more like Russia than the United States. I replied that in fact we might have to seek economic asylum for our clients in Russia, because these days there are fewer barriers to entry in Russia than in our country. The judge laughed ruefully. And then, shortly thereafter, he ruled against us. Not because he wanted to, but because the weight of case law against economic liberty was too great.

Such was the state of economic-liberty jurisprudence as we entered this millennium. Economic rights are consigned to the lowest level of judicial scrutiny—the so-called “rational basis” test. As most courts have applied it to economic regulations over the past eighty years, it has two features. First, the regulation doesn’t have to be rational. Second, it doesn’t have to have a basis.

It’s not much of a test, and almost no contested regulations ever flunk it. As a consequence, law students are taught that when the rational-basis test applies to a particular controversy between an individual and the government, the government always wins.

Leroy Jones had never heard about the rational-basis test, much less the privileges or immunities clause, when the government tried to destroy his dream in the early 1990s. Jones was a cab driver in Denver, working for the ubiquitous yellow cabs. He and some of his fellow drivers noticed an oddity in the Denver taxicab market. Cabs were abundant at downtown hotels and the airport. But if someone needed a cab in the low-income Five Points neighborhood, they were scarce.

Jones and three of his colleagues saw an opportunity. They decided to form a new taxicab cooperative, named Quick-Pick Cabs, that would primarily serve Five Points and other taxicab-scarce neighborhoods. They already possessed the requisite experience. They assembled the necessary capital. They collected hundreds of signatures from Five Points residents attesting to the need for additional taxicab service.

Indeed, the aspiring entrepreneurs had everything they needed to launch a profitable enterprise that would provide a valuable service—except, that is, a piece of paper from the Colorado Public Utilities Commission called a “certificate of public convenience and necessity.” No problem, reasoned Jones and his colleagues—their business was both convenient and necessary. But after the agency completed its review, it delivered to Quick-Pick Cabs the same verdict given to every other applicant for a taxicab permit since World War II: application denied.

The rules of the game were rigged decisively in favor of the three existing taxicab companies. A new applicant had the burden of showing not that there was a market need that was unserved, but that there was a need that could not be met by the existing companies. It was an impossible burden, exacerbated by the fact that the existing companies could intervene in the proceedings and bleed their aspiring competitor to death with massive and endless documentation demands.

Leroy Jones and his partners were denied the opportunity to pursue their business for the most arbitrary and protectionist reasons. One could hardly imagine a greater injustice. Yet when they went to federal court, they lost. Once again, there simply was not enough case law for the judge to render a favorable ruling. Having now been fired from the yellow cab company, Leroy Jones ended up selling cold drinks under the hot sun at Mile High Stadium, his dream of starting his own company crushed by his own local government. (Lest the reader get too depressed, this story has a happy ending—but I won’t reveal it until later.)

LICENSED TO EXCLUDE

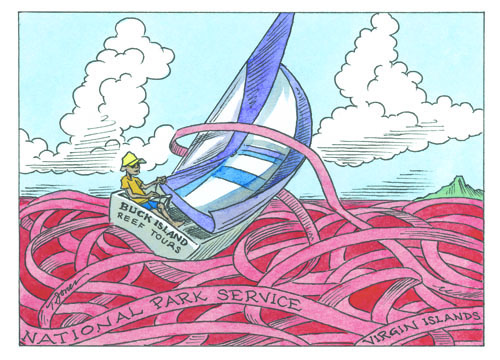

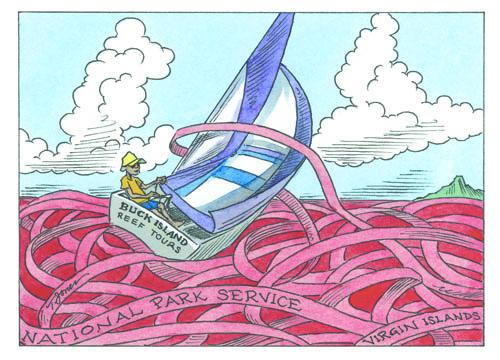

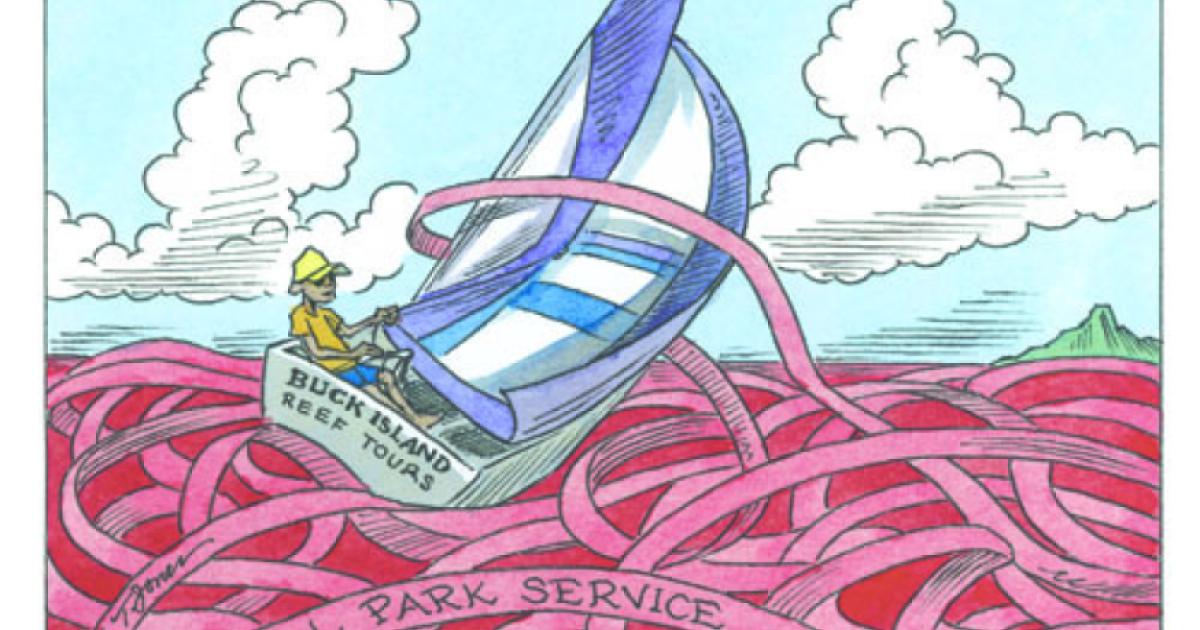

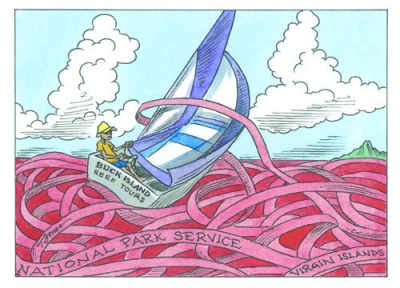

Most of the stories in similar circumstances, however, do not have happy endings. One of the saddest and most frustrating cases I ever litigated was on behalf of Junie Allick, a native Virgin Islands sailor. He made a living shuttling tourists to the beautiful coral reef at Buck Island. He was the only sailor in the business skillful enough to operate only with sails, as opposed to the gasoline engines that polluted the reef. But after the National Park Service assumed jurisdiction over Buck Island, it instituted an “attrition” policy to reduce the number of boat trips to Buck Island. For the first time, Allick had to navigate not only the waters off St. Croix but a sea of bureaucracy as well. Though Allick was a skilled sailor, he had never learned to read or write, and he failed to fill out forms required by the Park Service, which consequently shut his business down. Before long, not a single native sailor was left in the Buck Island excursion business.

Yet when we brought Allick’s case to court, the federal judge was incredulous that someone would waste the court’s time over a business that netted only $15,000 a year. He dismissed the case, thereby destroying the only livelihood Junie Allick had ever known.

The barriers encountered by Leroy Jones and Junie Allick are only the tip of the regulatory iceberg. In all, at least five hundred occupations, representing 10 percent of all professions, require government licenses. Frequently, the government boards that determine the standards are comprised of members of the regulated profession, who are invested with the coercive power of government and often wield it not for public health and safety purposes but to thwart competition. Similarly, government-imposed monopolies in businesses ranging from trash hauling to transportation to the transmission of renewable energy have the same effect.

The economist Walter E. Williams, in his classic book The State against Blacks, explained that occupational-licensing laws and entry-level business restrictions have the pernicious effect of removing the bottom rungs of the economic ladder for people who have little education and few resources. “The laws are not discriminatory in the sense that they are aimed specifically at blacks,” he explains. “But they are discriminatory in the sense that they deny full opportunity for the most disadvantaged Americans, among whom blacks are disproportionately represented.”

A good illustration of Williams’s point is Stuart Dorsey’s 1980 study of the Missouri cosmetology-licensing regime. Like most cosmetology-licensing laws, Missouri requires a practical “hands on” examination and a difficult written test. Dorsey found that blacks passed the performance portion of the examination at the same rate as whites, but failed the written portion at a much higher rate than whites. Thus were black candidates disproportionately excluded from a profession for which they were demonstrably qualified. In an economy that demands ever-greater educational qualifications for even the most basic jobs, there simply are not nearly enough avenues for legitimate entry-level businesses or occupations to sustain arbitrary regulatory obstacles. Those hurdles cast otherwise legitimate businesses into the black market, and many of their would-be participants into crime or welfare dependency.

Lurking behind most of these regulatory obstacles are special interests—usually labor unions, competing businesses, or both—that invoke the regulatory power of the state to keep newcomers out. In New York, for instance, the powerful transit-workers union manipulates the city council to maintain a ban on dollar vans, which operate mainly in the black market to carry scores of passengers in Jamaica, Queens, over fixed routes for a low price. Frequently, professions turn to the state to fix high barriers to entry, and then gain control over the licensing process. In the early part of the twentieth century, for instance, cosmetologists fought valiantly to free themselves from control by barber-licensing boards—only to turn around, once they succeeded, and lobby for cosmetology-licensing boards that they would control. Today, even professions that trigger few public health and safety concerns, such as interior designers and florists, seek shelter from marketplace competition through licensing schemes. As a consequence, government-enforced cartels now are ubiquitous.

Professions requiring more advanced skills, such as law and medicine, typically persuade lawmakers to forbid paraprofessionals, who offer their services at much lower cost, forcing them to become fully licensed even though they seek to engage in only a small, specialized part of the profession. As a result, they penalize both the would-be paraprofessionals and the consumers who might wish to use their services.

Perhaps the most troubling example in that regard is my own profession. Lawyers operate state bar associations that rigidly control entry into the profession. They expansively define the unauthorized practice of law so as to prevent skilled paralegals from making low-cost services available to people for routine transactions such as tenant evictions and simple wills, divorce decrees, and bankruptcies. The arbitrary barriers raise the cost and limit the supply of the most basic legal services. Surely regulation is sufficient to weed out incompetent paraprofessionals, but the bar typically opts instead for prohibition, the better to protect its cartel.

Equally pernicious are teacher certification schemes. As a certified teacher, I can attest that none of my required classroom instruction (all of which was state-required) enhanced my core subject-matter competence. Despite the fact that they often turn out ill-trained teachers, schools of education fiercely defend their monopoly status over teacher certification, resisting alternative certification and entry into teacher ranks by professionals who are demonstrably competent in their subject matter. The scheme ensures that many bad teachers enter the school system while many good teachers are kept out.

Licensing is not a proxy for competence, neither in teaching nor in many other professions. However, because licensing typically requires many hours of prescribed training, it is an effective means of limiting entry into professions. Licensing requirements are lucrative for schools that teach the prescribed courses and insulate licensed practitioners from competition. But they result in higher prices and fewer choices for consumers and destroy economic opportunities.

SAFEGUARDING A RIGHT

Such special-interest legislation greatly concerned the framers of our Constitution, who sought to prevent it. James Madison argued in The Federalist No. 10 that one of the strongest arguments for republican government is “its tendency to break and control the violence of faction.” By faction Madison meant what today is called a special-interest group: “a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” One means to limit the evil of faction, Madison observed, would be to control its liberty of operation (as we see today in the form of campaign contribution limits and other devices), but Madison denounced such cures as worse than the disease. The better course in dealing with the problem of faction, he offered, was “controlling its effects” by “rendering it unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression.”

The constitutional mechanisms designed in part to control the evils of faction were many, including the establishment of a federal government with limited and defined powers; the requirement that congressional action be taken only to promote the general welfare; separation of powers; an independent judiciary empowered to strike down unconstitutional laws (as described by Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist No. 78); specific limitations of government power such as prohibiting the impairment of contracts; and the Bill of Rights, including the protection of unenumerated rights in the Ninth Amendment. Madison’s argument also provided a philosophical foundation for the privileges or immunities and equal-protection guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment a century later.

Specifically, the framers understood that two of the principal objects of factions were to gain power over the property of others and to restrict their liberty. Thus the Fifth Amendment prohibited Congress from infringing liberty or property without due process of law, and from using the power of eminent domain except for public use and with just compensation. The Fifth Amendment’s due process guarantee later would be replicated in the Fourteenth Amendment, aimed in that amendment at curbing the power of state governments.

One of the foremost liberties threatened by the evil of faction was economic liberty. As Timothy Sandefur explains in his recent book, The Right to Earn a Living: Economic Freedom and the Law, American law inherited from its British forebears the principle that “people have the right to work for their subsistence, to open their own businesses, and to compete against one another, without government’s interceding to confer special benefits on political favorites.” British courts refused to enforce monopolies because they violated rights granted by the Magna Carta. As Sir Edward Coke observed in the Case of the Tailors of Ipswich in 1615, “at the common law, no man could be prohibited from working in any lawful trade,” and “the common law abhors all monopolies, which prohibit any from working in any lawful trade.”

Adam Smith likewise extolled the importance of freedom of enterprise in his Wealth of Nations:

Embracing that tradition, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Everyone has a natural right to choose for his pursuit such one of them as he thinks most likely to furnish him subsistence,” and a “first principle” is the “guarantee to everyone of a free exercise of his industry, and the fruits acquired by it.” Likewise, Madison declared, “That is not a just government, nor is property secure under it, where arbitrary restrictions, exemptions, and monopolies deny to part of its citizens that free use of their faculties, and free choice of their occupations.”

Those principles were embodied in the Virginia Declaration of Rights in 1776, which in turn influenced the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. The first article of the Virginia Declaration of Rights provides that “all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights,” which include “the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing happiness and safety.”

Economic liberty was expressly protected in the U.S. Constitution by such provisions as the due process clause, which protects life, liberty, and property; the contract clause, which forbids state interference with contracts; the privileges and immunities clause, which gives to anyone traveling to other states the same rights as citizens of those states; the commerce clause, which prohibits protectionist trade barriers among states; and the prohibition against the taking of property through eminent domain except for public uses. The right to pursue a trade or profession also was one of the “unenumerated rights” protected by the Ninth Amendment.

The promise of opportunity and its protection by the rule of law propelled American enterprise and made our nation a beacon of opportunity, luring to our shores countless newcomers hoping to earn a share of the American dream. One would think that such principles would protect a man like cabdriver Leroy Jones in pursuit of his livelihood. After all, the regulations he faced led to a government-created taxi oligopoly, closed to entry or competition from outsiders. It was procured and maintained by the existing companies, not for the protection of the public but for their own benefit. Those factors would place the regulations squarely within the crosshairs of the constitutional provisions designed to prevent special-interest groups from using government power to serve their interests through monopolies. And yet when he went to court to protect the freedom of enterprise that is every American’s birthright, Leroy Jones came away empty-handed—just like countless other entrepreneurs who have sought to invoke judicial protection for their economic liberty.

A PATTERN OF BLIND DEFERENCE

It is difficult to appreciate today’s evisceration of the right to economic liberty without considering relevant U.S. Supreme Court cases—three in particular. In the 1955 case of Williamson v. Lee Optical, the court sustained a statute prohibiting opticians from duplicating old or broken eyeglass lenses, or from fitting old lenses into new frames, without a prescription from a licensed optometrist. The challenged regulation stifled a legitimate business and raised costs to consumers—not to protect the public, but to insulate licensed optometrists from competition for lucrative services. Yet the court had no trouble sustaining it. In a decision by the self-styled champion of the common man, Justice William O. Douglas, the court ruled that even though the “law may exact a needless, wasteful requirement,” it is “for the legislature, not the courts, to balance the advantages and disadvantages of the new requirement.”

What is perhaps the quintessential modern economic liberty decision came twenty-one years later in City of New Orleans v. Dukes. There the court was presented with a law that destroyed for many the classic entry-level enterprise: hot-dog pushcarts. The plaintiff had operated her pushcart in the French Quarter for many years until the city decided to prohibit them—except for two vendors whose businesses were “grandfathered.” The court of appeals found the prohibition totally arbitrary and irrational, and struck it down. But the Supreme Court sustained the law, declaring that “this court consistently defers to legislative determinations as to the desirability of particular statutory discriminations.”

How complete this deference has become is illustrated in a more recent case, FCC v. Beach Communications, decided by a unanimous Supreme Court in 1993. There the court considered a federal statute that subjected to regulation satellite master antenna television (SMATV) operations that encompassed more than one property owned by different people, but exempted such operations when they were confined to buildings owned by the same owners. Because SMATV does not use public rights of way, the court of appeals could not discern any reason for Congress to draw the dividing line where it did—and to inflict very divergent consequences based on the distinction—so it struck the provision under the equal protection test. The Supreme Court overturned the court of appeals decision, setting forth the extreme deference to administrative discretion in a set of rules implementing the rational-basis standard:

- 1. “Equal protection is not a license for courts to judge the wisdom, fairness, or logic of legislative choices. In areas of social and economic policy, a statutory classification . . . must be upheld against equal-protection challenge if there is any reasonably conceivable set of facts that could provide a rational basis for the classification.”

- 2. “On rational-basis review, a classification . . . comes to us bearing a strong presumption of validity, and those attacking the rationality of the legislative classification have the burden ‘to negative every conceivable basis which might support it.’ ”

- 3. “Equal protection ‘does not demand for purposes of rational-basis review that a legislature or governing decision maker actually articulate at any time the purpose or rationale supporting its classification.’ ”

- 4. Because the government does not have to articulate its rationale, “it is entirely irrelevant for constitutional purposes whether the conceived reason for the challenged distinction actually motivated the legislature.”

- 5. Finally, “a legislative choice is not subject to courtroom fact finding and may be based on rational speculation unsupported by evidence or empirical data.”

Talk about an uphill battle! This is the nearly impossible burden litigators challenging economic regulations face when they go to court—and why the courts felt compelled to turn away the claims of Leroy Jones and Junie Allick.

The framers of our republican system of government never intended the courts to blindly defer to legislative decision-making, especially where the challenged laws were procured to advantage special interests and exact a large toll on precious individual liberties. But decisions such as those discussed here have obliterated the constitutional protections the framers carefully crafted to arrest the evils of faction and to protect individual rights. As the framers understood, only the courts can effectively police the boundaries of legitimate government action. But decisions like these make legislators the judges of their own power, and too rarely do they act with restraint.

Even worse, many regulations are imposed not by elected representatives, who are at least theoretically accountable to the people, but by regulatory agencies that are not democratically accountable at all. Most such agencies are either made up of members of the regulated industry or susceptible to special-interest influence. Their cumbersome rule-making procedures are opaque and often mystifying to ordinary people. Yet the courts accord them the same vast deference they give to elected representatives, no matter how irrational, self-serving, excessive, or oppressive their regulations may be.

Those who bear the burden of economic regulation rarely have the resources to compete effectively in the political marketplace or administrative arenas against powerful special-interest groups, and so their constitutional rights fall by the wayside. This fate has befallen economic liberty not because judges are consistently restrained in exercising their powers—after all, courts strike down laws every day. Rather, it is the result of judges relegating economic liberty to a subordinate, almost completely unprotected status.

That was not at all the fate our Constitution’s framers intended. Economic liberty was intended to be protected among the foremost of our civil rights, and an unfortunate decision of the U.S. Supreme Court heralded an era of judicial abdication that now has lasted nearly 140 years. But the path toward reclaiming protection for freedom of enterprise finally is before us.

Leroy Jones’s case is one step on that path. A federal judge examining the Denver taxicab oligopoly concluded that under the rational-basis test, he could do nothing to bring down the barriers that separated Jones and his colleagues from fulfilling their entrepreneurial aspirations. But fortunately, while the case was pending on appeal, the battle was won in the court of public opinion. In the light of media sunshine and an outpouring of public support, the economic barriers fell. Editorials and exposés pressured the state of Colorado to deregulate entry into the Denver taxicab market.

Jones and his colleagues, realizing that their fight had broad ramifications, renamed their company Freedom Cabs. Today, dozens of purple Freedom Cabs provide transportation to Colorado residents and visitors, along with the opportunity for co-op members to own their own businesses, while Jones and others take their place in the pantheon of Americans who refuse to cede their economic liberty.