- Budget & Spending

- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- World

- Contemporary

- Economic

- Campaigns & Elections

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- The Presidency

- History

A young physician refers to the president of the United States as “the crackpot in Washington who is ruining the country.” A businessman decries his “socialistic tendencies”; another denounces him as a “despot.” A banker claims the president is wrecking the banking system. The Republican Party proclaims National Debt Week and reminds Americans that deficit spending is passing a mountain of debt onto future generations. It is, one prominent Republican maintains, “the crime of the century.”

The target of these overheated condemnations is not President Barack Obama. Rather, these were routine comments about President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935–38 during the heart of the New Deal, culled randomly by this writer from a single collection at the Hoover Archives, a historical treasure trove at Stanford University. Later in the decade the tone and content of the criticisms would change as war clouds gathered in Europe and Asia, but in the mid-’30s the New Deal’s critics focused on its economic policies and the intervention of the federal government into worlds where it had never gone before in peacetime.

My foray into the archives casts doubt on two assertions that have been made so often that they seem to be treated as fact.

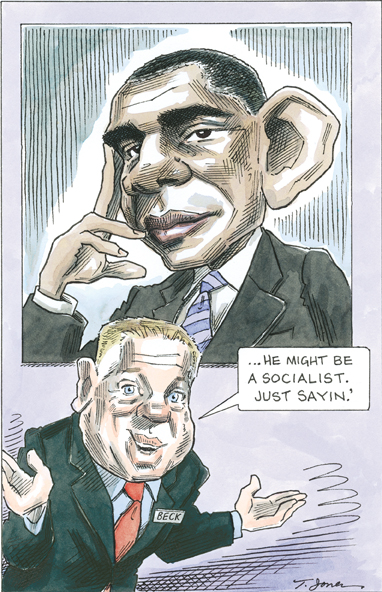

The first is that Obama faces slurs and slanders of unprecedented magnitude. This is attributed sometimes to racism but more often to the coarsening of the public dialogue arising from the decline of newspapers and the rise of talk radio, 24/7 cable news, and an Internet that puts legions of amateur bloggers on an equal footing with professional journalists and historians.

The second assertion is that conservatives or Republicans are out of ideas and time, a contention made provocatively by Sam Tanenhaus in his new book, The Death of Conservatism. “Today’s conservatives resemble the exhumed figures of Pompeii, trapped in postures of frozen flight, clenched in the rigor mortis of a defunct ideology,” Tanenhaus writes.

According to Stanford historian David M. Kennedy, today’s Republicans instead closely resemble their counterparts of seven decades ago who fought a rearguard action against government spending and what they saw as unwarranted intrusion by the federal government into business activity. This was the line taken even by relatively progressive Republicans, such as Alf Landon of Kansas, the Republican nominee who lost decisively when FDR won a second term in 1936. Landon had prominently opposed Social Security, enacted the year before.

“Most of the serious criticisms we’re seeing today of Obama—the size of the stimulus package, the soaring national debt, even the dimensions of the health care bill—are by-products of the Republican critique of the New Deal,” Kennedy told me. Kennedy, who won the Pulitzer Prize for history in 2000 for his masterful book Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945, believes there is an inherent tension between support for programs such as Social Security and concern about burdening our children’s children with a crushing public debt. Kennedy sympathizes with the FDR-Obama side of the argument, but he considers the opposition legitimate and is not ready to write an obituary of either the Republican Party or the conservative movement.

INCIVILITY: AN AMERICAN POLITICAL TRADITION

By and large, Republicans as a party—and conservatives as the driving force within it after Barry Goldwater won the GOP presidential nomination in 1964—did fairly well in the latter half of the twentieth century. It’s true that the Democrat FDR (who, as he put it, redefined himself from “Doctor New Deal” to “Doctor Win-the-War”) won third and fourth terms in 1940 and 1944 as the United States and its allies defeated Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan; his successor, Harry Truman, won in 1948. But since then, Republicans have won eight of fourteen presidential elections.

The campaign centrism of the only two-term postwar Democratic president—Bill Clinton—was itself a recognition by the candidate and his strategists that conservatives were a powerful force in America. They still are. Although only 28 percent of voters identified themselves as Republican in a Pew survey (38 percent said they were Democrats and 34 percent independents), some 40 percent of Americans classify themselves as conservative and 35 percent as moderate (with only 21 percent as liberal), according to a summertime Gallup Poll. That conservative number hasn’t changed much since Ronald Reagan was in the White House in the 1980s.

What also hasn’t changed much, unfortunately, is our tradition of verbally savaging even the best of our presidents. This began in the early years of the Republic. The Aurora, then a well-known publication in Philadelphia, on March 4, 1797, summed up George Washington’s eight years in office by asserting that he had carried “his designs against liberty so far as to have put in jeopardy its very existence.” (Italics in original.)

Abraham Lincoln was described by C. Chauncey Burr of New York in 1864 as “the gorilla tyrant who has usurped the presidential chair.” To be sure, such language was inflamed by a fratricidal Civil War that claimed the lives of more than 600,000 Americans, and rhetorical excess was to be expected.

But there was no similar basis for the relentless calumny against FDR that went on throughout the twelve years of his presidency. In his valuable book The Coming of the New Deal, historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. quotes a Republican congressman delivering a Lincoln’s Day address in 1934 in which he compared FDR unfavorably to Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini. Also typical was one of several attacks written by Merle Thorpe, a frequent anti-FDR commentator of the time, in the Nation’s Business: “We have given legislative status, either in whole or in part, to eight of the ten points of the Communist Manifesto of 1848 and . . . done a better job of implementation than Russia.”

The most unrestrained of today’s anti-Obama extremists may have an edge on their predecessors in sheer goofiness. The notion that Obama was born in Kenya or is a secret Muslim has embedded itself in conspiracy theories accepted by untold thousands of Americans. But in terms of viciousness, I think the FDR haters were the worst, perhaps because I have never forgotten a nasty rhyme from my boyhood during the 1940 re-election campaign that was at once anti-Semitic, targeting the president, and (as we would have said then) anti-Negro—the part of the slur directed at Eleanor Roosevelt.

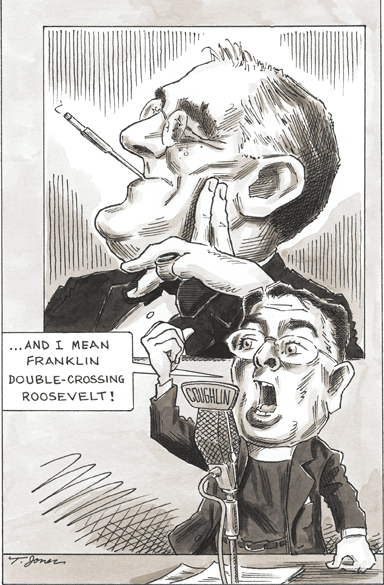

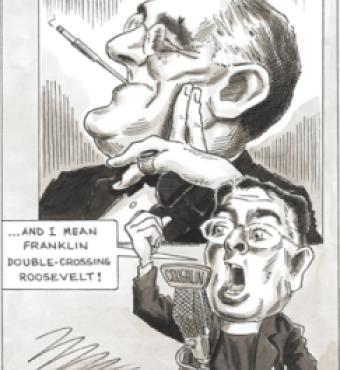

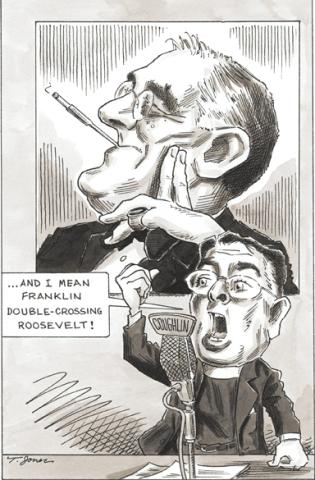

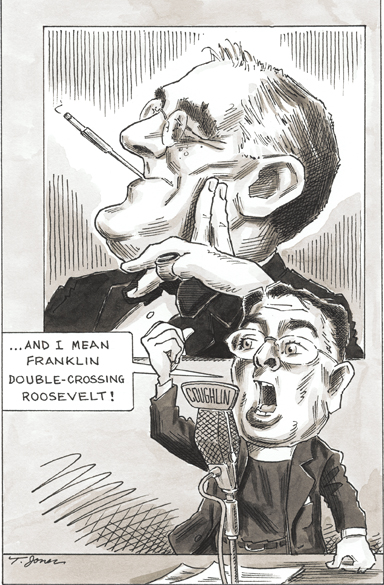

A Detroit radio priest, Charles Coughlin, seemed to be locked in a perverse competition with Gerald L. K. Smith, his Protestant equivalent in hatemongering, to see whose attacks on FDR could be more vile. Marquis Childs, a liberal columnist, in a September 14, 1938, piece in the New Republic (also culled from the Hoover Archives) linked “Roosevelt phobia” to anti-Semitic and antilabor sentiment. A familiar refrain, wrote Childs, was that “the president has brought a lot of radical Jews to Washington and they’re running the government.”

OPPONENTS OF ALL VARIETIES

The archives reminded me that what Richard Hofstadter called “the paranoid style of American politics” has always existed side by side with legitimate opposition—and that neither has changed as much as we might think. Hofstadter himself held that the heart of the New Deal was a shift in temperament rather than a change in governing philosophy. In other words, Roosevelt changed many things, more often than not for the better, but, with the exception of public-power developments, almost always within the framework of American capitalism.

Obama also operates within that framework. He is no more a radical or a socialist, let alone a despot, than was FDR. Nor has he challenged private ownership of anything. Based on his performance to date, Obama also shares with FDR a dubious achievement—“conspicuous failure to produce economic recovery,” to quote David Kennedy’s book on the New Deal. Kennedy sees Roosevelt’s achievements as nuanced and limited by reliance on the word security: Social Security, to be sure, but “security for capitalists and consumers, for workers and employers, for corporations and farms and homeowners and bankers and builders as well.”

Look closely at the Obama advocacies for stimulus, health care, and education reform, and one sees the same animating impulse as the New Deal: security and a better life for all Americans. Whether Obama will succeed is an open question, but I suspect that his opposition sees what he is about more clearly than Obama’s more impatient supporters. That’s why the opponents sound so much like the critics of the New Deal, which fell short of its bolder promises but nonetheless changed the lives of Americans for the better.