Politics is as old as war, and political calculation has been a part of military strategy since time out of mind. Alexander and Caesar made temporary alliances, spared the lives of combatants, granted benefits to subjugated peoples, and divided enemies not from any humanitarian impulses but from canny political assessment. Turning an adversary into an ally makes for shrewd military politics. Numbers matter in conflict, so increasing the size of an army or fleet by winning over a neutral or a belligerent to one’s side could spell the difference between victory and defeat.

In its contemporary version, the United States has embraced an elaborate and financially costly strategy known as Winning Hearts and Minds (WHAM) among the populations of Iraq and Afghanistan. The vast expense of these two contemporary WHAM campaigns casts doubt on the strategy’s use in other violent theaters.

The utter destruction of uncongenial neighbors has represented the more routine practice in the history of warfare. “Better a dead adversary than a possibly treacherous foe” often summed up the warrior’s thinking. Ancient and modern generals put to the sword not only enemy troops but whole populations. Warfare retained its highly lethal character for civilians for centuries. As recently as World War II (1939–45), military action included massive bombings of civilians and combatants alike. In fact, governments singled out cities for broad aerial bombing and nuclear destruction.

But after 1945, a political form of warfare, in which civilian sympathy mattered greatly, came to the fore. It was not new, but rather another ancient style of fighting seemingly made new by instant “experts” and television commentators. (In all the great recorded wars of ancient times, great captains such as Darius, Alexander, and Hannibal waged pacification campaigns as part of their conquests.) Instead of two conventional armies with similar weapons squaring off on a battlefield, the combatants are unevenly matched. Known by a variety of terms—irregular warfare, insurgencies, partisan warfare, people’s war, guerrilla warfare—this form of conflict features few conventional battles. One side, the insurgents, resorts to asymmetric approaches (sneak attacks, hit-and-run tactics, sabotage, assassinations of civil authorities) to defeat its better-equipped adversary. On the other side, the counterinsurgent armies struggle to govern, sustain civic services, and impose peace and stability. The insurgents carry out pinprick assaults to disrupt the government’s writ and install their own brand of political order.

Insurgents notched an impressive string of victories on unconventional battlegrounds at the expense of traditional armies. Mao Zedong’s “people’s war” in China established the paradigm during the 1930s. The next decade saw America’s Office of Strategic Services aid French Resistance fighters in irregular warfare against their German occupiers. After World War II, the principles of prolonged insurgent warfare were picked up by Cuba’s Fidel Castro, Algeria’s Houari Boumédienne, and Mozambique’s Eduardo Mondlane, who ousted established regimes or colonial governments. The 1939–45 world war weakened colonial powers, which also had to face the rising tide of anticolonialism sweeping the globe, often in the form of insurgency.

The target of both sides in this type of war is the people, who are caught in the middle of what normally is a form of civil war. The populace is the source of intelligence, recruits, funds, or food. Gaining the complicity of the population—if not the outright loyalty—against the other side is the objective of the struggle between insurgent and counterinsurgent. In this quest, the people’s security, rather than material benefits, matters most. Individuals and groups decide to extend or deny assistance based on their likelihood of survival.

Today insurgency and irregular warfare preoccupies the United States chiefly in Afghanistan but also in the Philippines, Yemen, Pakistan, Iraq, and the Horn of Africa. Russia is fighting an insurgency in the Caucasus; India wages an anti-insurgent campaign in its central region; and Thailand resists insurgents in its southern tier. The circumstances vary from place to place, but one constant of modern-day insurgencies is their focus on the people at the center of the conflict. Thus the political dimension forms a vital part of this way of war.

What is so different today in the American way of counterinsurgency, however, is America’s lavish expenditures on the targeted population. Much of this effort is too costly and too ineffective. In the past, protection, safety, and survival alone were sufficient inducements to an embattled community. Today, winning hearts and minds has evolved in American hands from basic security to far-reaching, infrastructure-building enterprises.

IRAQ: SHAKING OFF PERVASIVE VIOLENCE

For years after the intervention into Iraq in March 2003, the United States military executed its most successful WHAM campaign ever during the course of a full-blown insurgency. The Army and Marines won over enough Sunni tribes in central and western Iraq to defeat the Al-Qaeda-backed insurgency against the American-led coalition. The complete story of the astounding turnaround in the ground war is still emerging.

Sound counterinsurgency principles began to be used well before the now-famous “surge” of 28,500 additional combat troops into Anbar province starting in February 2007. Operation Iraqi Freedom traversed from a lopsided victory of high-speed, armor-led, blitzkrieg warfare, which pulverized Saddam Hussein’s regular Republican Guard divisions in three weeks, to a grinding, bloody insurgency. From then on, the American-led coalition faced a metastasizing resistance movement, except in the Kurdish regions. The U.S. military thereupon transformed itself from a superkinetic conventional-war machine to a counterinsurgency force. Individual Army and Marine officers, without top-down direction, independently mounted WHAM operations two years before the publication of the U.S. Army and Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual in December 2006.

The overtures to divide enemies, split friends from foes, and court sympathizers were implemented piecemeal, gradually, and through trial and error. Brigade and battalion commanders sat down to sip tea and talk with Iraqis. Average Iraqis grew desperate at the savage, daily violence in their midst; they turned to American troops to protect them. To help the U.S. forces, they passed along tips about arms caches and the whereabouts of the insurgents. Americans alone offered an escape hatch from the pandemic of violence engulfing their neighborhoods.

At its core, the WHAM strategy entailed protection and security for local people, not material inducements. Tellingly, the key factors for WHAM centered on staunch protection and martial cooperation against a common enemy rather than extravagant U.S. largess.

Brenda Dwiggins, a chaplain’s assistant assigned to the 1st Marine Logistics Group who serves on a special Iraqi Women’s Engagement (IWE) team, greets a boy in Anbar province. Such teams were set up to provide security and medical care for Iraqi women, who are discouraged from interacting with men in public.

Standing up neighborhood-watch-type defenses or interacting with existing militias flourished when indigenous forces believed they had a better-than-even chance of prevailing against murderous insurgents. In some sense, then, WHAM resembled leasing or renting hearts and minds, not winning once and forever the populace’s loyalties. Pulling out on an embattled people, under these circumstances, almost ensures that they will look to others for their safety. In Iraq, for instance, after U.S. combat forces completed withdrawing at the end of August 2010, some former Sunni allies drifted back into the Al-Qaeda camp. Groups of Sunnis have made this move for safety, money, or both. Amid violent and chaotic conditions, ordinary people will adapt and accommodate to survive.

But America and allied nations achieved many positive results in Iraq. They contributed to making Iraq the twelfth-fastest growing economy in 2010. Moreover, its economy is expected to grow at a 7 percent clip for the next several years and Iraq should have a budget surplus this year. Unemployment, at 15 percent, is high, but down from the astronomical heights of three years earlier. (Some American communities have a higher rate.) Electrical production, a key indicator during the hot summer months, was up by 40 percent from prewar levels but is still inadequate because of increased demand for air conditioning. The International Monetary Fund concluded that “Iraq has made substantial progress since 2003.”

The coalition forces brought about a degree of stability in Iraq by 2008 through their increased presence, sound counterinsurgency strategy, effective WHAM tactics, and collaboration with Sunni tribes hard pressed by Al-Qaeda’s callous disregard for human life. The nation-building infrastructure played a much less important role. In fact, many of the construction programs went uncompleted. Half-built schools, abandoned medical clinics, and partially finished office complexes for civic services litter the countryside—a testament to failure rather than achievement. The huge financial outlays, half-completed buildings, and charges of corruption raise doubts that endeavors on the Iraq model could succeed elsewhere.

AFGHANISTAN: SEEKING LEGITIMACY

As in the Iraq War, the United States placed a premium on protecting Afghans, starting with the first days of the American-led intervention in fall 2001. Special Operations Forces (SOF) and other operatives concentrated on teaming up with the Northern Alliance movement, which had fought the Taliban regime in Kabul from its base inside the Panjshir Valley in the country’s northeast since 1996. Supported by U.S. Air Force and Navy warplanes, the SOF-Northern Alliance forces swept the Taliban rulers from power. By early 2002, the Taliban had been routed, and Osama bin Laden and his inner circle of followers fled across the border into Pakistan.

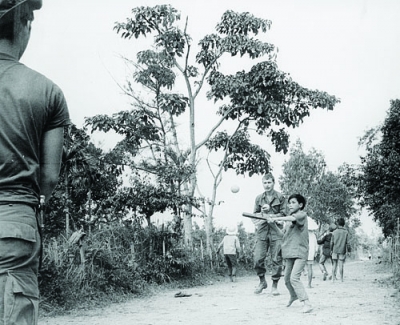

American soldiers play baseball with the children of Ap Uu Thoung hamlet in 1970. The troops were part of pacification operations in their district. Not until the Vietnam War did the United States military start to think seriously about the elements of low-intensity conflict.

The U.S.-spearheaded intervention broadened into a NATO mission that implemented many nation-building endeavors. The NATO presence was less an army of occupation than an armed charity operation to lay the economic and political foundations for a severely underdeveloped country. This reconstruction program embraced projects in social welfare, public works, democracy, and social engineering. Among the most important was the establishment of Afghan National Security Forces, to include an army and police forces.

The period between the 2001 invasion and the inauguration of a new American president in 2009 begs for clear and dispassionate analysis. The Taliban staged a rebirth and remounted attacks that accelerated from mid-2005. Many blame its resurgence on Washington’s diverted attention to Iraq after its 2003 intervention there, but a more penetrating examination is needed to account fully for the NATO setback. For our purposes, suffice to say that when the new U.S. administration took office in early 2009, the Taliban had reasserted its deadly influence in the south and east. A new approach was needed, and the Pentagon and White House decided on a shakeup in leadership.

Population protection lay at the heart of the change in counterinsurgency strategy set forth by General Stanley McChrystal, who assumed command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and U.S. Forces-Afghanistan in June 2009. General McChrystal came to the Afghan position after extensive experience waging a highly effective, lethal campaign against Al-Qaeda and other militants in Iraq. The new top commander acknowledged many times the importance of enemy casualties. Even so, he noted another metric in the shadow conflict with the Taliban. He declared: “The measure of effectiveness will not be enemy killed. It will be the number of Afghans shielded from the violence.” Population protection thus became his touchstone for progress against the insurgents.

WHAM meant going beyond the mere passive acceptance by the population of the ISAF presence. It entailed the Afghans’ cooperation with U.S. and NATO forces at first. Most telling, it meant their transferring of loyalty and legitimacy to the Kabul government. When the locals volunteered intelligence tips as to the whereabouts of Taliban fighters or arms caches, they demonstrated a commitment to the coalition mission and their own government. The rising numbers of Taliban killed and captured testified to the stream of tipoffs to SOF, which relied on informants as well as electronic intercepts. This information was not just a raw metric but an indicator of headway among the locals.

WHAM also envisions local people joining in their own defense. Calling people to their colors always ranks near the top in the WHAM scheme of things. One reason is that counterinsurgency campaigns are troop-intensive undertakings, requiring as a rule of thumb perhaps twenty to twenty-five counterinsurgents for every thousand residents. Indigenous recruits have been used in most modern-day counterinsurgencies. The British recruited Malays in their Malayan emergency, the United States depended on South Vietnamese forces, and both the French and the Portuguese relied on local manpower in their counterrevolutionary wars in Algeria and Mozambique, respectively. Not all the counterinsurgent forces in Afghanistan need to be U.S. troops; ISAF forces and Afghan units also count. Enlisting men at arms not only enlarges the counterinsurgent forces but also decreases the insurgent recruitment pool.

General Stanley McChrystal, then-commander of NATO and U.S. forces in Afghanistan, works during a flight. Despite his emphasis on inflicting enemy casualties, McChrystal stressed that “the measure of effectiveness will not be enemy killed. It will be the number of Afghans shielded from the violence.”

Most vitally, the tribesmen or villagers’ enlistment in government forces can foster loyalty toward the established government. If such ties endure (without a defection or desertion), then the “leasing” of hearts and minds can become more enduring. Even if not, it is wise to recall that battlefield politics, like ordinary politics, rely on temporary alliances: a “leasing” of confidence may be all that is needed and attainable in the run-up to victory.

WHAM, as currently waged in Afghanistan, resembles a political election within a mature democracy. The contending parties make promises to the “electorate” to gain and hold their votes. NATO and its Afghan allies promise and implement a future filled with modern roads, schools, hospitals, and even clean politics. This philosophical game plan covers societal aspects well beyond the strictly military field. It means connecting average Afghans to their government first through honest and fair elections, and then through effective and honest rulers.

Assembling credible and efficient institutions has not been without difficulties in a politically and economically backward land. All societies labor under the burden of official graft, but in Afghanistan the problem reaches pervasively from the village to the presidential palace. The scale of illicit activities is evidenced by reports of between $1 and $2.5 billion in cash being spirited out of Afghanistan to the United Arab Emirates in 2009. The latter figure represents about a quarter of the Afghan gross domestic product. The United States and its allies have set up Afghan anticorruption task forces to investigate graft, train investigators, and dispatch advisers to reduce high-level governmental malfeasance. The issue loomed so large that General David Petraeus tasked one of his rising stars—Brigadier General H. R. McMaster, who is also a Hoover research fellow—to lead anticorruption efforts, pointing to how far U.S. counterinsurgency efforts can venture from basic WHAM endeavors that focus on protecting locals. It would have been far better had the sitting government undertaken anticorruption steps, rather than the United States.

ULTIMATELY, A HUGE BOTTOM LINE

The cost of WHAM reconstruction proves it is a very expensive way to wage counterinsurgency. The cost of the Afghanistan war reached $107 billion for the 2010 fiscal year. The overall costs of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars accounted for 1.9 percent of our nation’s GDP. This figure falls well below the burdens of the Korean and Vietnam wars, which came in at 3 percent and 2 percent, respectively, but the difference lies in the duration of these conflicts. The fighting in Afghanistan has passed its tenth year, surpassing even the protracted Vietnam conflict. To many Americans, the U.S. anti-insurgency conflict in Afghanistan is remote, derided by critics, and surrealistically detached from future terrorist threats. The money set aside for Afghan infrastructure could be invested in American infrastructure, with its deteriorating highways, roads, bridges, viaducts, and transportation systems.

And, above all else, the massive and accumulating federal debt overshadows national priorities and elections. Interest payments are projected to consume increasing amounts of government spending.

This portends fiscal austerity. Military expenditures are likely to be squeezed because they are considered discretionary spending. Other large parts of the federal budget, such as Social Security and Medicare, constitute mandatory entitlements. These and other social-welfare programs account for nearly 60 percent of the budget. The Pentagon is already alert to the deficit projections and has called for deep cuts in future defense budgets.

The stratospheric spending of the anti-insurgent struggles in Iraq and Afghanistan is likely to reopen the debate on the proper strategy to combat insurgent-based terrorism. As Al-Qaeda or its imitators show themselves in Yemen, Somalia, and North Africa, Washington will need to think carefully about costs and effectiveness as it decides how to move against these militant havens, ungoverned spaces, and failing states. The extent and type of WHAM policy are likely to stand front and center in such deliberations. The approach cannot be ignored, but the degree of protection of civilian populations may differ. People-centric campaigns are likely to assume more modest and cheaper approaches to win (or lease) the loyalty of rural villagers and urban dwellers by deploying a slender U.S. presence against insurgents. The special-operations role in the Horn of Africa, Colombia, Yemen, and the Philippines offers examples of limited civic-action assistance and training. This type of micro-scale, relatively inexpensive WHAM may never return the United States to the days when a handful of Green Berets with shoulder bags of medicines worked among the Montagnards in Vietnam, but the basic concepts are apt to endure. As Roger Trinquier, one of the French high priests of counterinsurgency, wrote: “The sine qua non of victory in modern warfare is the unconditional support of a population.” Perhaps “unconditional support” is more a hope than a realistic attainment, but the counterinsurgents’ focus must always be, as General McChrystal put it, to gain popular “trust and confidence,” which must then be directed to the host nation.

In fact, the slogan “winning hearts and minds” should undergo a subtle change: winning hearts and minds for the host nation. It must be the core mission of U.S. forces to transfer not only cleared, held, and built-up areas of land, but also the loyalty of that land’s inhabitants to their own governmental institutions.