In January, I spent a week in Hong Kong as a guest of the regional government. I met with civil servants, business people, and members of think tanks and the Legislative Council, and saw enough PowerPoint slides to last me a lifetime. I heard so many opinions on Beijing’s “one country, two systems” strategy that I lost track of them. I saw protests for and against every major government policy. But there was no sign of anxiety that China and the United States might be on a collision course.

Should there have been?

There are many reasons to say no. China’s “peaceful development” (as the government now calls it, after deciding that “peaceful rising” sounded too threatening) since the 1980s has mostly dovetailed with American strategic interests. On the whole, China is an enthusiastic free trader, American markets welcome cheap Chinese goods and capital, and China is a responsible partner in regional security issues.

But there are also reasons to say yes. By 2008, China’s softly-softly approach had been so successful that some neighbors felt—particularly after the financial crisis—that instead of staying on the Chinese bandwagon, they needed to form a counterbalance against it. With cooperation now working less well, China took a harder line.

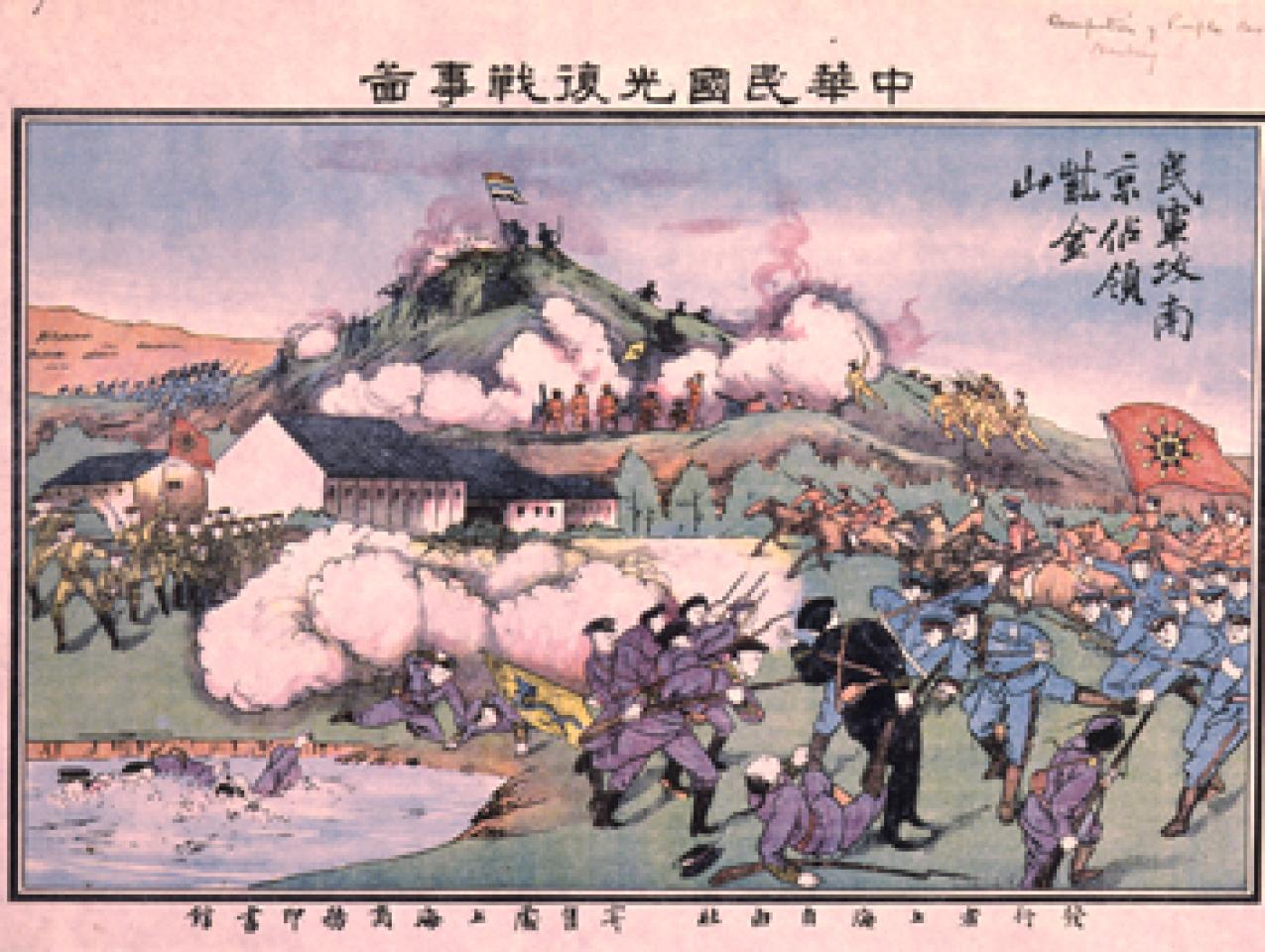

Against this background, strategists were tempted to draw what Edward Luttwak has criticized as “the inevitable analogy” between China and late 19th-century Germany. Back then, Britain was a globocop, guaranteeing free trade and financing industrial revolutions that would make other countries rich enough to buy British goods. But Britain succeeded too well; by 1900 Germany had become rich enough to be a rival, talking of forming a European Customs Union and shutting Britain out of it. Britain’s economic success brought on strategic disaster.

The inevitable analogy implies that China is rerunning this scenario. By “Finlandizing” the West Pacific and South China Sea, it suggests, China is leaving the region’s governments unable to ignore Beijing’s lead—even if that includes shutting the U.S. out of the world’s most important markets.

That would threaten vital U.S. interests, but is it really what China is doing? Rather than comparing China with Germany a century ago, the other rising economic giant of the late 19th century—America itself—might be a better analogy. Today, the American globocop enjoys a huge military lead over China, just as the British globocop enjoyed a huge lead over the United States around 1900—but not over Germany. The U.S. around 1900 had enough battleships to keep British fleets out of American waters, just as China today probably has enough submarines, mines, and missiles to keep American ships out of its littoral; but 19th-century America, like 21st-century China, was in no position to project power in long-range campaigns of conquest. Germany, of course, was all too able to do this.

Late 19th-century America seems to be a better analogy with China than late 19th-century Germany, and U.S. strategy should aim to nudge China toward recognizing this. Xi Jinping needs to take Teddy Roosevelt as his guide, not Kaiser Wilhelm, speaking softly while carrying a big stick rather than noisily demanding a place in the sun. The big lesson of 1914, in fact, may be that globocops must send clear signals. After 1890, Germany consistently misjudged British intentions, and marched to war in 1914 still half-expecting that Britain would not honor its treaty obligations to Belgium.

If anything, American signals today are even more mixed than Edwardian Britain’s. I saw this in person in mid-2011, when I was invited to a meeting in Canberra to discuss the difficult choice Australia faced between its main strategic partner (America) and its main economic partner (China). The conversations were tense; every option seemed worse than the last, and all seemed to hinge on what America might do. But just a few months later, Barack Obama announced the pivot toward Asia. “Let there be no doubt,” he told the Australian Parliament. “In the Asia-Pacific of the 21st century, the United States of America is all in … We will keep our commitments.” West Pacific governments stiffened their spines; despite Chinese protestations, a flurry of collective security agreements followed.

But then it stopped, with Australia again leading the way. A new Defence White Paper in May 2013 dropped the tough talk and cut military spending back. A strategic pivot is only as valuable as the intentions behind it, and America’s partners in the West Pacific just don’t know if the United States will be there for them. “A distant water can’t put out a nearby fire,” says a proverb that Vietnamese officials like to quote to Americans. China’s deputy chief of staff, however, has put the matter more bluntly: “U.S. power is on the decline, and leading the Asia-Pacific is beyond its grasp.”

The people I met in Hong Kong were probably right not to worry about conflict in the West Pacific—yet. But in the absence of a more credible American commitment to defend its allies and open markets, that will change.