- World

- Contemporary

- History

In twentieth-century Russian literature, Boris Pasternak stands out as a great metaphysical poet, as evidenced by his verse collection My Sister, Life, written during the revolutionary years. A central theme of his poetry, as well as of his magnum opus, the novel Doctor Zhivago, is man’s destiny in revolutionary times. Pasternak felt a strong affinity with European cultural and philosophical tradition, and his contribution to European literature is considered to be equal to that of Rainer Maria Rilke or T. S. Eliot.

Facing the trials of his cruel and tumultuous epoch, Pasternak retained the moral values and artistic conceptions that characterized the pre-revolutionary era, which he inherited from his parents and their artistic milieu. Pasternak the thinker, the witness of an epoch, stands as high as Pasternak the poet. Whether condemned to silence or allowed to publish translations or sporadic selections of poetry, his very existence served as proof of the tenacity of art. Despite the stifling situation in the country and the demands imposed on artists by the Soviet government in the darkest periods of Stalinist rule, the poet considered it his duty to confront and combat the regime’s efforts to (as he put it) “trample the artist in man.” His rebellious stance toward the Soviet regime led to a direct confrontation with the state when he sent his novel to be published in the West.

Pasternak was the first writer in the Soviet Union to receive the Nobel Prize. Thanks to his courage, Russian culture was able to overcome the legacy of Stalinist ideology and give rise to the new, nonconformist, and dissident trends in literature best exemplified by the works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sinyavsky. One of the strongest manifestations of Gorbachev’s decisive break with communist ideology was the publication in the Soviet Union of Doctor Zhivago, which had been banned in Pasternak’s native country for 30 years.

Boris Pasternak’s parents moved from Odessa to Moscow in 1889, not long before Boris was born. His father, Leonid Osipovich Pasternak, taught at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture and was a well-recognized painter. The poet’s mother, Rozalia Kaufman Pasternak, had displayed from earliest childhood exceptional musical ability, giving her first concert as a pianist when she was eight years old. Marriage and the birth of her first child put an end to her professional career, however.

Their son Boris, emulating his father, set out studying art but switched from drawing to music in 1903. His accomplishments are evident in three works for piano, two Preludes and the Sonata in B Minor, which have been recorded and performed several times since the early 1970s.

When Boris showed his musical works to Alexander Scriabin in 1909, his idol’s response exceeded all expectations: “Scriabin heard me out, approved, encouraged me, and gave me his blessing,” wrote Boris later. At Scriabin’s suggestion Boris, a freshman at the law school of Moscow University, decided to transfer to the history and philology department, where he became an ardent follower of the neo-Kantians of the Marburg School, even to the point of studying at Marburg University in Germany for a semester in 1912.

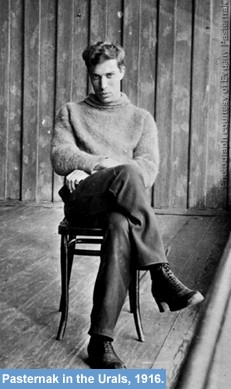

Pasternak plunged into writing poetry, making his literary debut in the collection Lirika (Lyrics), published in May 1913, shortly before graduating from university. The following winter saw publication of his first book, Bliznets v tuchakh (A Twin in the Clouds).

Pasternak wholeheartedly greeted the February revolution of 1917 that overthrew the tsarist government. It was not individual parties or political slogans that attracted him but the general spirit of freedom and unanimity, which he saw as uniting not only inimical groups and classes of society but even the trees and the land—nature itself. Much less enthusiastic was his reaction to the Bolsheviks’ accession to power in October 1917. He was appalled by the violence that it brought about.

In the winter of 1918–19, Pasternak started compiling a book of poems that became a major work of twentieth-century Russian poetry, Sestra moia—zhizn’ (My Sister, Life). Although many of Pasternak’s new poems could not find their way into print, the period from 1917 to 1921 saw handwritten copies of his poems circulated widely. Valery Bryusov claimed that no poet since Pushkin had achieved such popularity on the basis of manuscript copies as Pasternak did in those years. With the introduction of the New Economic Policy in March 1921, private publishing houses resumed their activities. Sestra moia—zhizn’ was printed in April 1922 in Moscow and a few months later reissued in Berlin.

In August 1922 Pasternak and his wife, Evgenia Vladimirovna, left for Germany. In the winter of 1922–23 two of Pasternak’s books were published in Berlin: a new edition of My Sister, Life and a new, fourth book of poetry, Temy i variatsii (Themes and Variations). In March 1923 the poet returned to Moscow, for his stay in Berlin had led him to the conclusion that conditions in Soviet Russia were more propitious for art. During Pasternak’s absence, however, Soviet literature had changed for the worse. Political servility had increasingly become the norm in the cultural realm. Typical of these new tendencies was Vladimir Mayakovsky’s group Lef, which advanced the theory that new, revolutionary art should renounce traditional aesthetic values and serve the needs of socialist production and construction. The traditional forms of art—lyrics, novels, symphonies, and paintings—were not needed in the new social conditions.

The years 1928–30 marked profound upheavals in the very foundation of Pasternak’s thinking. Crushed by the certainty that moral values were disappearing from Soviet life, particularly values he had found in the revolution—personal independence, magnanimity, honesty, humanity, and the flexible (as Trotsky had called it) atmosphere around art—and driven by forebodings of the imminent end of all real literature, Pasternak hastened to finish all the works previously conceived or begun.

In one of these works, Safe Conduct (Okhrannaia gramota), begun in 1927, Pasternak contrasted the first years of the revolution, when even under harsh conditions art had not been degraded, and the current situation, in which art seemed defenseless before the attacks on its independence. Safe Conduct was condemned for the customary sins of the time (“idealism,” “bourgeois restorationism,” and so forth), receiving not one sympathetic response in the Soviet press. In March 1933 it was banned by the censors and was not republished in the Soviet Union for 50 years.

Then began a period that both Pasternak and his biographers have called the “interval of silence.” From 1932 until 1940 he wrote only a handful of lyrics. The poet attributed his silent period to the worsening political climate. Two years earlier, in 1930, Pasternak had begun a stormy romance with Zinaida Nikolaevna Neigauz, who eventually left her husband, the pianist Genrikh Neigauz, and married Pasternak after he divorced Evgenia.

During a visit to Georgia in November 1933, Pasternak—in response to government reproaches of his work—translated several poems on civic themes, including two odes to Stalin by his Georgian friends Nikolai Mitsishvili and Paolo Iashvili. Pasternak saw Stalin as the cementing force in the country and hoped that the period of terror was drawing to a close and that the Soviet Union was witnessing the triumph of the principles of social justice and reason.

In February 1934 Nikolai Bukharin, the former leader of the “rightist” opposition, was appointed editor in chief of Izvestia, the second most important newspaper in the USSR. Bukharin felt that the most crucial task of the hour was to effect a transformation in art, education, and science; like Gorky he believed that culture was the sole bastion against the fascist onslaught. Bukharin completely changed the profile of Izvestia, attracting the best literary talents of the time. The brightest star in this galaxy was Boris Pasternak, whose translations created a kind of antiphony together with the editor in chief’s own statements. No other paper or journal gave so much attention to Pasternak as did Izvestia under Bukharin.

Within the context of this liberal “offensive,” Pasternak was seen as the “premier” Soviet poet by the literary establishment close to Gorky and Bukharin. He was given an honored (and hitherto unimaginable) place in official surveys of Soviet literature and received much attention at the First Congress of Soviet Writers, where Bukharin declared that true Soviet poetry was embodied in the work of three poets: Pasternak, Selvinsky, and Tikhonov. Pasternak never felt as close to the Soviet regime as he did during 1934. In December he wrote to his father in Germany, “I have become a part of my times and the state, and its interests have become my own.”

The assassination of Kirov on December 1, 1934, and Gorky’s death in June 1936 produced a palpable change in the political atmosphere. During the “Ezhov terror” many in the Soviet Union lost friends or relatives, including Pasternak, whose close friends in Georgia, Paolo Iashvili and Titsian Tabidze, fell victims to the great purge. In this “time of absolutely unbearable shame and grief, I was ashamed that we kept on moving about, talking and smiling,” Pasternak confessed later.

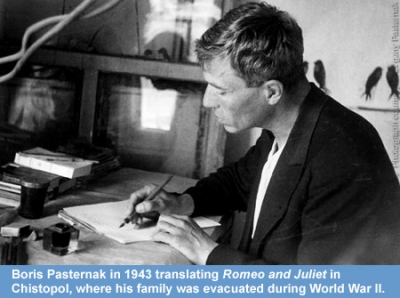

The poet’s reflections and moods at this time appeared in his translation of Hamlet, which was undertaken at the suggestion of Vsevolod Meierkhold, a great artist of the theater, who had long dreamed of producing Hamlet. But on January 8, 1938, Meierkhold’s theater was closed down, and in June 1939 he was arrested as an enemy of the people. Writing about this event to his cousin in Leningrad, Pasternak said, “It is indescribable, and all of it touched me closely.” The director’s arrest forced Pasternak to hurry rather than break off the project, which he finished at the end of 1939, when it had become dangerous even to mention Meierkhold’s name. His translation of Hamlet remains an exceptional phenomenon in Soviet literature.

Pasternak’s collection of poems Na rannikh poezdakh (On Early Trains) came out in the summer of 1943. Evidently the initiative to publish this book—his first new verse collection in 10 years—came from the literary authorities whose task was to demonstrate that Pasternak had been rehabilitated as a lyrical poet.

In 1945, in London, Lindsay Drummond published a book of translations of Pasternak’s prose. This detailed analysis of the poet’s works and place in the history of Russian literature offered in the introductory article by Stefan Schimansky to this volume broke new ground by concluding that Pasternak had a special intellectual kinship with Pushkin.

In October 1946 Pasternak met a 32-year-old staff member of the journal Novyi mir (New World), Olga Ivinskaia. Soon rumors of their romance were circulating throughout Moscow literary circles. The poet’s late love lyrics, many pages in his novel Doctor Zhivago, and many lines from his translations of Petöfi and Goethe’s Faust mirror the vicissitudes of their relationship.

The Cold War, beginning in 1946, led to the Soviet Union’s isolation from the West; in September of that year, Pasternak’s name began to be mentioned in the press in increasingly sinister contexts. He was accused of “ideological neutrality and a lack of political awareness.” Simultaneous attacks were made on critics and journals that had been too indulgent toward Pasternak’s poetry. A few months later, his translations of Shakespeare were criticized for their ideological deficiencies.

In the spring of 1947 the campaign against Pasternak intensified. Believing that the matter might end with his arrest, Pasternak recalled his cousin Alexander Freidenberg, who had disappeared in 1937: “Of course I am prepared for anything. Why should it have happened to Sasha and everyone and not to me?”

By the fall of 1947 rumors had reached Moscow that Pasternak had been nominated by a group of English intellectuals for the Nobel Prize. Before World War II, no Soviet author had been considered for such an honor, although in the early 1920s, when Gorky lived outside Russia, he had been a candidate. In 1946, Swedish left-wing writers had proposed Mikhail Sholokhov, Stalin’s favorite, for the Nobel Prize. When Boris Pasternak’s name began to be put forward, a complicated situation arose.

The Soviet officials did not want to make Pasternak a martyr in the West or spoil the chances of their official favorite, Sholokhov. Striking a person close to Pasternak seemed to them an effective way to paralyze his literary creativity and erase him from the memory of his readers. Thus in the late autumn of 1949 the secret police arrested Olga Ivinskaia. State Security Minister Viktor Abakumov declared that Pasternak was an English spy and that Ivinskaia was planning to flee abroad with him. She was charged with anti-Soviet political activities and sentenced to five years in the camps. As for Pasternak, he believed that Ivinskaia’s fortitude during the investigation saved him from arrest.

If the authorities had hoped Ivinskaia’s arrest would silence Pasternak, they were mistaken. Plagued by the fate of Olga in prison, and uncertain about how these events would reflect on his own situation and the life of his family, Pasternak returned to his work on Doctor Zhivago with redoubled energy. The words of one of its heroes, Evgraf—“And remember: you must never, under any circumstances, despair. To hope and to act, these are our duties in misfortune. To do nothing and to despair is to neglect our duty”—reflect the author’s moods during those gloomy days.

Doctor Zhivago was written over 10 years, from the summer of 1946 to December 1955. When Stalin died, on March 5, 1953, changes in the life of the country became noticeable almost immediately, but Pasternak was skeptical about the readiness of the authorities to embark on far-reaching reforms. In the winter of 1955–56 he presented the typescript of the final text to the journals Znamia (in which the poetry from Doctor Zhivago had appeared earlier) and Novyi mir (with which Pasternak had signed a contract in 1947, later to be annulled). This was a trial move; from the very beginning Pasternak did not believe that his new work would prove acceptable to the Soviet press.

In May 1956, after hearing that he had just completed a novel devoted to the revolutionary epoch in Russia, a young Italian journalist, Sergio D’Angelo, rushed to see Pasternak and proposed to issue an Italian translation of the novel at the Feltrinelli publishing house. After some hesitation the author brought the manuscript from his study and gave it to the journalist, saying, with a laugh, “You are hereby invited to watch me face the firing squad.” (At this time no Soviet writer could be in direct contact with foreign publishers without the approval of Soviet officials.)

Throughout the next two years, Soviet officials used coercion, threats, and outright lies to prevent Pasternak and Feltrinelli from bringing out the novel in Italian and other translations. But these clumsy attempts to prevent its publication only promoted the swift growth of interest in Doctor Zhivago. Its first printing of 6,000 was sold out on the first day, November 22, 1957. The Italian translation was accompanied by a deluge of articles and notices in the European and American press, with much attention devoted to the banning of the novel in the Soviet Union and the Soviet attempts to stop its publication abroad. No work of Russian literature had received such publicity since the time of the revolution.

When Doctor Zhivago appeared in the West, the poet, who had been subjected to decades of silence in his native country, suddenly became a celebrity abroad. The Western audience sensed in him the organic, indissoluble tie with European culture. To the foreign correspondents who visited him, Pasternak’s solid background in philosophy, study in Marburg, refusal to consider Marxism the only acceptable worldview, lack of the usual clichés of official Soviet ideology, faithfulness to the principles of humanism and absence of class biases, and lively and free relationship to religion and the Bible seemed out of keeping with stereotypical portraits of the Soviet intellectual.

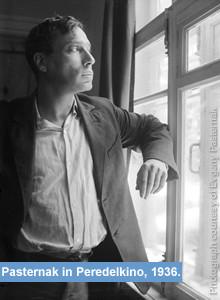

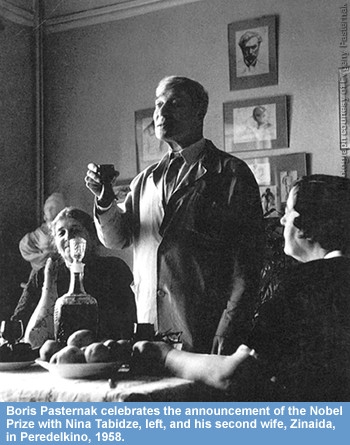

The Western press began touting Pasternak for the Nobel Prize in the spring of 1958. When the Swedish Academy awarded it to him later that year, it cited him “for his important achievement both in contemporary lyrical poetry and in the field of the great Russian epic tradition.” Soviet authorities proclaimed that awarding the prize to Pasternak, as well as the publication in the West of Doctor Zhivago, was an act of political provocation. The tense and threatening atmosphere surrounding the author and his relatives was created not only by attacks in the Soviet press but also by choreographed popular indignation—threats of mob violence, shouts of hooligans on the streets, and so forth. Western newspapers reported that Pasternak’s home in Peredelkino was surrounded by a police detail and that one needed a permit to visit him.

Under pressure from the Soviet authorities, Boris Pasternak was forced to decline the prestigious award. His Nobel Prize was accepted by his son, Evgeny, 30 years later.

Pasternak died of lung cancer on May 30, 1960. The authorities prohibited any announcement of his funeral and made attending it an act of disloyalty. Two thousand mourners arrived. The secretary of the Writers Union carefully noted the names of those writers who had dared to attend.

Andrei Sinyavsky, who wrote the introduction to the book of Pasternak’s poetry that was published in the Soviet Union in 1965, and Yuli Daniel carried the casket’s lid. Both writers were later arrested and imprisoned for publishing abroad.