- Economics

- US Labor Market

- History

- Contemporary

- US

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- The Presidency

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

Recorded on July 12, 2017

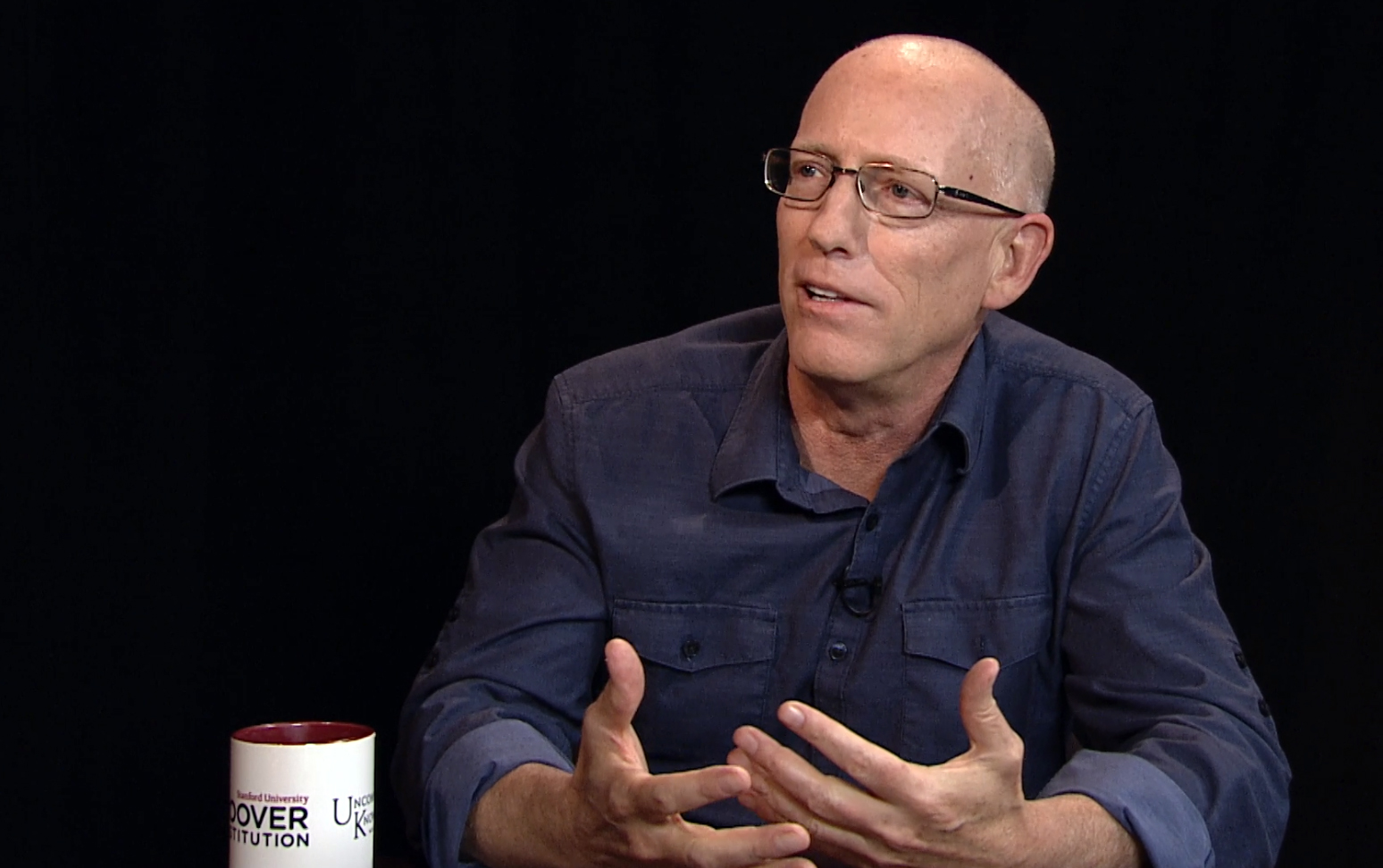

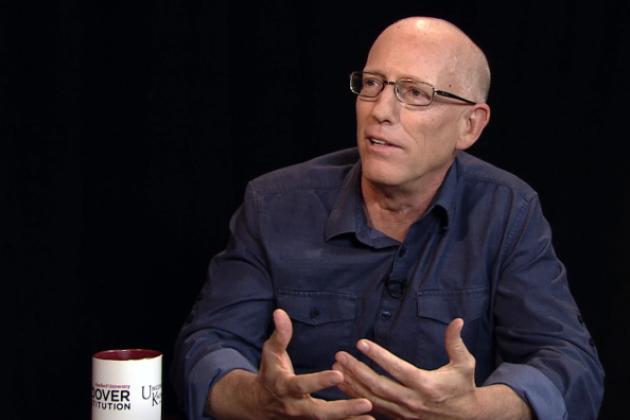

The Dilbert cartoonist and political philosopher Scott Adams sits down with Peter Robinson to discuss his book How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big. He discusses with Peter his theory of “talent stacking,” the idea that rather than being an expert in one particular skill (i.e., Tiger Woods and golf), one can become successful by stacking a variety of complementary nonexpert skills. Adams demonstrates how talent stacking has been beneficial in his life because he has stacked cartoonist skills with his MBA and experience in corporate environments to create a wildly successful comic strip that resulted in spin-off books, a television series, a video game, and merchandise. His business skills gave him the tools to create a business satire cartoonist and the skill set to manage the business that evolved from that strip.

Adams also discusses how he uses his Dilbert blog to discuss his political philosophies and observations about the Trump administration. He wrote blogposts about the 2016 election and predicted that Donald Trump would win based on President Trump’s talent stack as a media mogul and businessman who had spent significant time in the public eye so was immune to scandals and thick-skinned enough to handle what the media and other politicians would throw at him. Adams argues that President Trump is one of the best branders, influencers, and persuaders he has ever seen, in that the president uses persuasive techniques in debates and on social media as a way to get people to do what he wants. Adams contends that President Trump’s persuasive techniques will help solve the problem of North Korea because he has already set up China to get involved by intimating that it tried and failed. Adams believes this will cause China to get involved to save face.

Scott Adams and Peter Robinson finish by chatting about Adams’s views on the story arc of life. Adams says that he believes he started intentionally selfish so that by the end of his life he can give away all of his wealth, knowledge, and wisdom, a process he says he has already begun. They also briefly discuss his new book, Win Bigly, about the persuasive strategies of Donald Trump.

Scott Adams is releasing his new book, Win Bigly, in October 2017.

Transcript

Peter Robinson: The Dilbert Principle: leadership is nature’s way of removing morons from the productive flow. With us today, the man behind the Dilbert Principle, for that matter, the man behind Dilbert itself, cartoonist, author, and it turns out, political philosopher, Scott Adams. Uncommon Knowledge now. Welcome to Uncommon Knowledge. I'm Peter Robinson. Raised in a small town in upstate New York, Scott Adams graduated from Hartwick College in 1979. He worked for a number of years for the Crocker National Bank in San Francisco, earned an MBA at the University of California at Berkeley, and then went to work for another number of years at Pacific Bell, a period during which he began getting up early each morning to draw cartoon strips. By the middle of the 1990s, Mr. Adams had at last become a full-time cartoonist, and the name of that cartoon strip is Dilbert. Today Dilbert appears in thousands of newspapers in more than 50 countries and in more than a dozen languages. Mr. Adams is the author of the bestselling book, The Dilbert Principle, of many collections of his cartoons, and most recently of, How To Fail At Almost Everything And Still Win Big, subtitle, Kind of The Story of My Life. Recently, Mr. Adams has also attracted attention for his blog, where he has been offering advice to his fellow Americans on how to think about President Trump, and advice to President Trump on how to think about America. Scott Adams, welcome.

Scott Adams: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Peter Robinson: Let's get this out of the way right away, you and Donald Trump. President Trump's approval ratings are the lowest on record, and among academics and journalists and for sure professional people here in Northern California he is almost universally derided. Here's you on your blog, quote, "Trump doesn't have one talent that is best in the world, but he does have one of the best talent stacks I have ever seen." Close quote. Okay, so what's a talent stack? Then tell us about Donald Trump.

Scott Adams: Well, first of all, let me clarify that when I talk about Trump, I'm talking about him through a persuasion filter. In other words, I have a background as a hypnotist, I'm a trained hypnotist and I've been studying ...

Peter Robinson: My eyelids are going heavy even now.

Scott Adams: I have studied persuasion in all of its forms as part of what I do as a writer and cartoonist. I noticed in candidate Trump at first, a type of persuasive skill that you just don't see. He brought the full package of persuasion. If you're not a student of it you would miss it entirely. In other words, if you didn't know anything about the techniques he was using, you would say, "What's this crazy random chaotic clown who keeps doing things? Hey, he won again. He won the primary. Well, that was luck. But he'll never win the ... Uh oh, what just happened?" I predicated all of this, I think, a year and a half before election day. I predicted that he would win by a lot. Now, you could argue whether the electoral college victory was a lot and you could argue about the popular vote. The fact is, he played a game that had a set of rules, and he won by a lot on the game he was playing, which was the electoral college.

Peter Robinson: Yes.

Scott Adams: He didn't win the game he wasn't playing. I kind of assumed that didn't matter, and it didn't. When I talk about his talent stack, that's a little bit of some thinking from my book that you just mentioned. The idea is ...

Peter Robinson: Let's sell a few copies. It's a wonderful book.

Scott Adams: Thank you. There are two basic ways to really make a difference in this world and succeed. Here, success is not just financial, but just success in life. One way is to be insanely good at one thing, let's say Tiger Woods, you know, he's good at one thing. But you really have to be about one of the best in the world, depending on the thing you're doing, to really make a dent. All right? The other way you can do it is the way that I've done it, which is, I've compiled a set of complementary skills, and I'm not really the best in the world at anything, right? If you were to go into any crowded room you could find a better artist than me. It would be easy, because I just don't have much artistic skill.

Peter Robinson: For the sake of argument, I'll let you be self-denigrating, but go ahead.

Scott Adams: Well, I think anybody who studies cartoons would look at the page and say, "Well, there's the worst artist on the page." There's no false humility involved in any of that.

Peter Robinson: All right.

Scott Adams: I've never taken a writing course, but I know how to make short pithy sentences, so I'm good at that. I have a lot of business experience, because for 16 years I worked in the corporate world, so I had something to draw upon, which is the fodder for the strip. You could go down the line of what it takes to be a cartoonist, business skills for example. You know, I had my MBA from Cal. Those things all just work together really well, but I'm not great at any of them. I'm not Warren Buffett, my business skills, but I have enough to do this thing. They just work together well.

Peter Robinson: See this lovely image of, you stack this talent on this talent, on this talent, on this talent, and you end up with something that's pretty impressive.

Scott Adams: Right. Then the trick is that they have be complementary skills. So being able to be a speaker, being comfortable in this kind of format, works really well with being a writer. You know, if you have only the writing skills, where are you going to promote your book? They just work well together. Now, back to Donald Trump. If you look at the things he can do better than most people, he can definitely give a speech better than most people. But the experts will say, "Look at the" ...

Peter Robinson: He's no John Kennedy. He's no Ronald Reagan.

Scott Adams: Yeah, "He's no John Kennedy. Where's his soaring rhetoric.", and all that. Well, he doesn't have that, but the crowd loves him. He's funny, right? It's hard to be funny, and funny really helps your popularity, helps your persuasion. Again, he's not a standup comedian funny, but if you put him in a room, he would be one of the top 20% of funny people in a room, right?

Peter Robinson: Right.

Scott Adams: He's smart. Not the smartest person in the world. He's not the physicist who's going to solve the next great problem in physics, but he's clearly smarter than most people. Unambiguously, he's smarter than most people. He knows enough about government and how it works from the other side, because he dealt with it a lot, that he was no expert in government, but he knew more than somebody who wasn't involved in any way, right?

Peter Robinson: Right.

Scott Adams: He knew about being a boss. He knew about leadership. He knew about entering a field that he'd never entered before, because he'd done it a number of times. Which, by the way, is a usually a tell for what I call a master persuader, someone who knows persuasion and also has built a talent stack that can take them in a lot of different directions.

Peter Robinson: He goes from Queens to Manhattan. He goes from building to casinos. He goes from casinos to branding various items, and then he goes to becoming a television personality. Those are really quite distinct career patterns.

Scott Adams: Then president of the United States, and before that, candidate, a whole different job. The job of candidate is pretty different.

Peter Robinson: This guy's done a lot.

Scott Adams: Not only did he do those things, but he almost entered at the top. He was so strong going in, that he had just the whole package. Now, the other thing he has, which is a big deal, is that he brought the whole Donald Trump persona. Right? That allowed him, for example, to be largely immune from scandals that would pop up, because you knew that at some point during the election, somebody would say, "What about that thing you did with this or that woman?" You knew that was going to happen, right? And sure enough, the tapes that we all heard showed that. He was somewhat immune from that, because he'd started from the beginning, he'd said, "I'm no angel."

Peter Robinson: And his divorce from Ivana was on the front page of the New York Post day after day for weeks, back in the, whenever it was, early '90s. Nobody thought of him as a choir boy.

Scott Adams: Smart enough never to make a big deal about, I'm your family role model. Never sold himself that way, so he was never vulnerable to those attacks in the way that regular people would be. The other thing he has, and I think this comes with learning persuasion, is that he has the thickest skin. You know, he's accused of being exactly the opposite, because he always attacks back, and I can talk about that specifically, but imagine the amount of abuse that he clearly knew was going to come his way just by running, and then by winning it, it gets that much worse. He signed up for that. You know, you don't do that unless you've got a thick skin. Look at the stuff he's brushed off so far. It's really impressive.

Peter Robinson: Okay. Now, there you are during the presidential campaign, and you start blogging. I have to say, it gets my attention. Why would a guy who's a cartoonist have such fresh insight? Okay, so I'm looking at it. You're putting a distance between yourself, often quite a wry distance between yourself and Donald Trump. You said his policies weren't necessarily your policies. You were quite cagey about it all the time.

Scott Adams: Let me interrupt you there.

Peter Robinson: Go ahead, because I want to know where you stand, and you may not let me ask that. But go ahead.

Scott Adams: No, I'm going to volunteer that. Socially, I call myself an ultra-liberal, meaning that I'm more liberal than liberals. You couldn't get further from the Republican stand than I am. I'll give you an example. A normal liberal would say, "Drugs should be more legalized." I say that if you're over 50, your doctor should be giving them to you. Really, growing old sucks, and if you're 80, you should get LSD, you should get mushrooms, whatever it takes to make you happy. Wherever the liberal position is, I'm quite often even further to the left of that. I'll give you another example. Conservatives might want to ban abortions, liberals might want to say, "We would like that option," I go further to the left and say, "Men, stay out of it. Whatever the women figure out for how this reproductive right should be, how about we listen to them who clearly know everything we know about, meaning men, about the science and the details and the politics, but they have the extra appreciation, and more importantly, the extra responsibility." They take the responsibility of reproduction that men can’t take. In general, when people take on more responsibility, society often says, "We'll give you a little extra rights, a little consideration because you're doing something that's so important." I say in abortion, men should listen, and whatever women collectively agree with, I'm okay with that, wherever that goes. You can't get more left than that. Back to your point, and on stuff like international relations, what do we do with trade deals and stuff like that, my view is always the same: I don't know. The stuff is way too complicated for an average voter to figure out what to do with the TPP and, we don't know.

Peter Robinson: How ... You did ... I found this quotation, because I thought to myself, "I've got him." Let's see if I have got you. "Trump's value proposition is ... this is you on your blog. Quote, "Trump's value proposition is that he will 'Make America Great.' That concept sounds appealing to me. The nation needs good brand management." Whatever else is going on, issue, by issue, by issue, you look at this guy and say, "You know, he's my guy."

Scott Adams: Well, I'm not saying I'd say, "My guy." I say that he has a set of skills, which are extraordinary, and the thing I was most interested in was that the country could see it clearly without the filter put on it by the opposition because they're both painting each other terribly. In Hillary Clinton's situation, people know what a standard politician is. They could see through the attacks on the other side. We knew what we were getting, but with Trump, people didn't know what they were getting. At least half the country thought he was crazy Hitler. I had actually predicted, I guess before he was inaugurated, that you would see the following story arc develop because it just was obvious if you're trained in persuasion, it was going to go this way. It would start with, "Oh my God, we've accidentally elected Hitler, like how did this happen? How did half the country or so not know that we've elected a monster?" I figured, okay, after a few months of not doing Hitler stuff, it's just going to dissipate, and it has. By summer, I said the Hitler thing will dissipate, and it did, but it would be replaced with "But, he's incompetent. He's incompetent. He's incompetent". Sure enough, that was the big word of the summer up until now. I didn't see the Russia thing coming because that, that's hard to predict, but I've predicted that after the "He's incompetent" phase will come the, "Well, he did get a lot done, but we don't all like that. He did things we don't like, but he was awfully effective and he did do the things he said he was going to do. We just don't like those things." You're going to see that by year end, and in fact you're already seeing the turn.

Peter Robinson: Yes.

Scott Adams: It's visible now. You can see the turn happening.

Peter Robinson: Right. I want to return to Donald Trump and current politics in a moment. "How to Fail at Almost Anything and Still Win Big: Kind of the Story of my Life" is a book that combines a fascinating life story with insights from a fascinating mind, and also lovely, light touch with a prose that is so readable. A couple of moments from the book, and I just want to give a flavor of Scott Adams and the way his mind works. We have a very young Scott Adams dressed in a cheap three-piece suit, seated on an airplane to California next to a business man, and learning, I'm quoting from the book, "Goals are for losers". How do we get to that scene and how did you learn that lesson in that moment?

Scott Adams: Let me finish that story of the airplane, and then I'll extend that to systems versus goals. The person I chanced upon meeting, struck up a conversation with me, and part of the reason was because I was wearing a suit on an airplane and I was 21, I guess ...

Peter Robinson: You thought people dressed to go on airplanes.

Scott Adams: I'd never been on an airplane. I'd never been on one and I didn't know many people who had been. That's how small my town was and how small my experience was. I also didn't know how to pack yet, so I thought, "Well I'll just wear it. It won't get wrinkled". This gentleman I'm sitting next to started a conversation. He told me about his system for life, that the moment he would get a job, ideally a promotion, he would immediately start looking for his next job. His concept of what his career looked like was not a goal as in "I will get this job", it was a system where he never had the job he was going to keep. His system was that you're always looking for the next job and it's a better job. I extended that in the book. It's sort of my philosophy in life, is I look for a system instead of a goal. Now, would you like to hear the advantages?

Peter Robinson: I would. Well, first of all I want to make sure that ... I think I got it, because I read the book, but I want to tease it out a little bit. A goal is the pot of gold at the end of a rainbow. A system is something you do every day, it is a method, it is a means of approach. Have I got that? That's the basic distinction?

Scott Adams: Yeah, so far right.

Peter Robinson: Okay. Go ahead.

Scott Adams: For example, getting a specific job or promotion would be a goal, but going to college would be a system because you're doing it the whole time you're there, you're working on it, but you don't know exactly where it's going to go.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Scott Adams: You know your odds just got a lot better in a whole bunch of different ways. Any good system has that quality. You're doing it regularly and it increases your odds. I extend that to fitness and diet and jobs as well. The talent stack is a system. If you say to yourself, "Well, I've got these skills", and maybe you've got some natural ability, you know there's something about you that it would be hard for people to equal, you're just born that way. You got the gift of gab, you're handsome, you're whatever you want. You say, "Well, what goes well with that?" Then you build a system of learning those things and adding to those things. That would be one system. There are different systems for exercise and diet, et cetera.

Peter Robinson: Okay. I just thought, this entered my head, coach Belichick, coach of the Patriots, execute the plays and the score will take care of itself. That's exactly the same point you're making, isn't it?

Scott Adams: Well, to the extent ... The trouble is that football is such a constrained, man-made thing. Nothing really translates from it.

Peter Robinson: Right. It's all ... Okay. Here's another moment. You're working for years at a bank, and then you're working for years at a telephone company. Then all of a sudden you're one of the most famous cartoonists in America. How did that happen? The lesson here, again I'm quoting from the book is, "Luck can be managed, sort of." How did you manage those years? What was it, 14 years I think in corporate America?

Scott Adams: Yeah, 16.

Peter Robinson: 16.

Scott Adams: Well, when I say luck can be managed I mean this: if you wanted to be hit by lightning, let's just say that's something you wanted, most people would say, "Well, it's very unusual to be hit by lightning. It's just luck. There's nothing you could do about it." I would say there very much is something you can do about it. You can go outdoors. That would increase your odds. You can go outdoors when it's raining in a place that has thunderstorms. That would increase your odds. If that's not enough, sell all your possessions, move to the top of a mountain that has frequent thunderstorms, build a network of connected lightning rods and camp out with your hand on one, you're going to get hit by some freaking lightening. Right? When you say, "I don't know what to do. I'm not lucky. Luck can't find you", you can go find luck. The first thing I did when I got out of college in my small upstate New York life, is I said, "Where is all the luck?" I was thinking opportunity, but really they're so correlated. I said, "I got to get out of here." I said, California. I ended up in ...

Peter Robinson: Which leads to the three-piece suit in the airplane.

Scott Adams: Yeah. I actually traded my car to my sister for a one way ticket to California.

Peter Robinson: Really? Okay. Again, this is going to lead me from the book to current politics. I don't want to reveal just how at the moment. I'm quoting from How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big. Quote, "I ignored my father's advice to work for the Postal Service. I got into college without much help from my guidance counselor, and I stayed in school against my doctor's advice ...". You had mono and the doctor said you should drop out. You stayed in school. "... This was about the time that my opinion of experts, and authority figures in general, began a steady descent that continues to this day." I think I see another reason you like Donald Trump. You're subversive. You don't like being told what to do or looking up to anybody.

Scott Adams: You know, and part of it is life experience. The older you get, the more examples you see of "Hey, remember that food pyramid that we're all taught as a kid? Turns out there was no science to that. Hey, what about those vitamins you take, your one a day vitamin? That's been tested, right? Not really. There's no reason you take it once a day. All those vitamins and minerals should be delivered in different doses in different ways. By the way, we haven't even studied most of them. How about those eight glasses of water you were supposed to drink or something? Turns out, no science to that. What about the don't go swimming ...

Peter Robinson: After you eat.

Scott Adams: ... After you eat. Turns out, no science to that." The older you are, the more of these you've seen, the less your respect for the experts can be maintained.

Peter Robinson: Okay. Now this takes us right to the issues of the day. On your blog you have what are to me at least completely novel ways of looking at a number of issues about which I, because of the nature of my work at a think tank, thought I had read and heard everything. Here's one of them: climate change. "It seems to me that a majority of experts could be wrong whenever you have a pattern that looks like this. There is a severe social or economic penalty for having the 'wrong' opinion in the field. I agree with the consensus of climate scientists because saying otherwise in public would be social and career suicide for me, even as a cartoonist. Imagine how much worse the pressure would be if science was my career." Nothing about the science, you're just looking at the human psychology of the thing. Right?

Scott Adams: Well, that's at least half of it, the human psychology of it.

Peter Robinson: Okay.

Scott Adams: A lot of people who have not studied persuasion, for example, have never seen mass delusions explained to them in ways that just make your head explode. For example, a lot of people watching this have never heard of the McMartin School Case, where a whole bunch of kids allegedly said that they'd all been molested by their ...

Peter Robinson: Back in the 80s as I recall.

Scott Adams: I think so.

Peter Robinson: Yeah, late 80s, early 90s. Okay.

Scott Adams: You had all these people who had similar stories of molestation and satanic rituals and stuff. Apparently, and it turns out that all of it was false, because it's easy to manipulate kids into telling stories because you act like you want them to, and then they just do. There are lots of histories of mass delusions. In my world, it is common, and the examples I gave you, the food pyramid, et cetera, it's common for all the experts to be on one side and still be wrong. To the average person, that seems unusual. It's not unusual if you've expanded your scope and if you just look for these things and you see it everywhere. Somebody just sent me an article of 43 peer reviewed articles that were just removed from some publication, because it turns out somebody was gaming the peer review system. Here's the other part about climate science. Whenever you see a big, complicated projection model with lots of variables, and by the way there's not just one of them, there are dozens of them, and the ones that didn't work they throw away. There are lots of judgment about "we're going to adjust these numbers. We have good reasons. We're telling everybody you can peer review it, but we're making some human decisions". In that situation there's a level of complexity of these models that makes the likelihood that they're right start to approach zero as the complexity increases.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Scott Adams: Now, part of my perspective on that is that I used to do that. Not with ...

Peter Robinson: With the bank?

Scott Adams: Yeah, so for the bank I would do financial projections based on all these variables and assumptions and everything. I knew that I could give you any answer you wanted. I would ask my boss, "How do you want this to come out?", and then I would just sit there with my spreadsheet and put in numbers until it came out. That's my perspective, but if you haven't been through that world, if you haven't lived in the corporate world and seen how many experts were wrong ... Let me give you the anecdote that just popped into my head. Years ago, I worked in a lab in a phone company where we were testing cell phones. Somebody was trying to test if they would be dangerous with the EMF, or whatever it is, holding it up to your ear. The top engineer studies it. He looks at everything and he concludes, "No, there's no reason to be worried about holding these things up to your head." I talked to him privately and said, "Do you believe that? Would you hold the phone up to your head at hours at a time?" He said, "No. No way." This was the expert whose report the entire company made their decision on. He said, "I wouldn't do it."

Peter Robinson: One more quotation from your blog. We're still on climate science because I think it illuminates a certain amount about your approach. "If you believe that experts are good at predicting future doom, you are probably cared to death about climate change. But any danger we humans see coming far in the future we always find a way to fix." Then you note predictions of food scarcity, we haven't run out of food. Predictions we'd run out of oil. We have more energy than we know what to do with. "I refer to this phenomenon as the Adams Law of Slow-Moving Disasters. When we see a disaster coming- as we do with climate science- we have an unbroken track record of avoiding doom. If you ask me how scared I am of climate changes ruining the planet, I have to say it is near the bottom of my worries." Now because I'm humane, I'm going to give you a chance to take that back right now. You live in northern California, Scott.

Scott Adams: Now, most of you have been following the news. You saw that the Paris Climate Agreement, United States backed down.

Peter Robinson: Trump takes us out of it. Right.

Scott Adams: Before that happened, I have to say, I thought that thing was probably pretty useful. I thought, "Well, it's probably a bunch of really useful guidelines that would get us to at least reduce whatever this danger is." By the way, I completely buy the idea that humans are heating up the earth. I'm buying that, and then the experts weigh in on how much difference it would've made if we'd stayed in. It turns out, not really much of anything. It just wouldn't make much difference. I didn't know that. I actually thought independent of the science, I thought that that agreement would make us do things that would change things. Turns out, not so much. What did all the experts tell us before we actually looked at that agreement with some detail? They all said it's important, it's vital to the earth, it's vital to the survival of the earth. All the experts were lined up on that, I mean as much as they were lined up for climate science. Today good luck finding somebody who can still defend that agreement. Not talking about the science.

Peter Robinson: This is three weeks or a month or something like that.

Scott Adams: Yeah. It's only been a month and we've completely redefined what we thought was reasonable.

Peter Robinson: Okay. Now we have established that you have a fascinating story.

Scott Adams: Wait.

Peter Robinson: Go ahead.

Scott Adams: Can I just inject one more?

Peter Robinson: You can do anything you want to.

Scott Adams: My contribution, I think, to the conversation of climate science is to break it into three categories and to treat them with three separate probabilities. All right? We're all sort of guessing what are the odds that this is right. The basic science part, the chemistry, the physics, if you add the CO2 in a closed system, will it head up under these conditions, probably a solid. I'm not a scientist, but I would definitely believe the experts. Then there's the making the models part. Scientists are doing it, other scientists are reviewing it, they're using sciency things and logic and reason. I'm sure they're doing their best, but the odds of that being accurate are much lower. Indeed, there have been lots of climate models in the past that were wrong. The third part that doesn't get talked about is what I like to contribute to the conversation, which is the economic model. The science doesn't tell you what to do, how hard to do it, or when to start. Science doesn't do that. The economic model says, "Okay, if you're going to do something it's going to cost a lot of money, so you either start now or you hope you can wait till later." For example, I added solar panels to my house when I built it. I'll tie this to climate change in a second. When I bought them they said, "If you get these solar panels it'll pay itself off. It'll lower expenses in next years." That was true. It looks like that actually is happening. Was it a good idea economically for me to get those solar panels? Seems like it, right? It paid off just like they said. No, it was a terrible economic idea. My background was economics as well. The cost of the installation dropped by probably 50% in a couple years. If I had simply done nothing and waited for the technology to improve, I would've had a far better economic outcome. Likewise, with climate science, there's a lot happening that could be improvements in green this or that. I talked to an expert on nuclear stuff and he says fusion is actually almost solved ...

Peter Robinson: Really?

Scott Adams: Yeah. Apparently we're closer to just the engineering part than the science part.

Peter Robinson: Got it.

Scott Adams: These are enormous civilization changing developments. There also could be developments in the next say five years of scrubbers, ways to take things out of the atmosphere, maybe a better understanding of how it's all happening, which gives us a new clue. Waiting is often the smartest thing you could do. Take the year 2000 bug. Everybody said, "Hey, year 2,000 the world is going to fall apart." It looked like a year before that we didn't really have much of a plan or a mechanism to fix it. By the last few months, humans stepped up. Geniuses got involved. I mean, I wasn't watching it closely, but you know geniuses got involved.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Scott Adams: They probably built tools that allowed them to do a thing that they couldn't do quickly, quickly.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Scott Adams: Probably the same thing could happen in climate change. My point is, even if all the science stuff is exactly what the scientists say, and how would I know, I'm not a scientist, the economic part is just completely unfathomable. It's unpredictable by its nature. There has never been a good long-term economic model with lots of variables that worked out.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Scott Adams: It's something that just hasn't been done.

Peter Robinson: Right. Back to the contemporary political/cultural scene. Let me ask you to give some advice to people who could use it. Here's a category: Republicans and Conservatives who are having trouble with President Trump. Here's Bill Kristol. "The problem isn't Trump's Twitter. The problem is Trump's character". Here's George Will. "President Trump suffers from 'intellectual sloth and an untrained mind bereft of information and married to stratospheric self-confidence.'" People who are on his side to the extent that he lines up ideologically who just are beside themselves, what's your advice?

Scott Adams: Advice for them or for ...

Peter Robinson: Yes, no for them.

Scott Adams: Well, keep in mind that this is an arena in which people take sides, and once and they join their team there isn't much that can get them off the team. You can get them to talk less, I suppose, and success would do that. There's no substitute for winning. If President Trump does well, if things go well, the economy does well, ISIS stays beaten back as they are, if North Korea, we find some reasonable solution there, which would be hard, people are going to forget all that. They're just going to reinterpret their impression of what they saw in the past.

Peter Robinson: Okay. Democrats who are not only uniform in denouncing President Trump, but seem completely fixated on getting him out of office, removing him from office, and even seems to me, I could be wrong about this, but it seems to me that there's not much policy work being done, there's just nothing happening on the Democratic party except denunciations of President Trump. Your advice for the Nancy Pelosi's and the Maxine Waters' of the world?

Scott Adams: It seems to be true that whichever party is out of power is the ridiculous one, but there's a reason for that. I mean, there's a perfectly logical reason. When Obama was in power it seemed like the right was ridiculous. It's like, "What about your birth certificate? Are you a secret Muslim?" It looked crazy. It just looked crazy. The people out of power, the last thing they want to do is put forward a positive proposal, because first of all it's not going to happen because they're not in power. The other side isn't going to say, "Yeah, that was a good idea. We're just going to use your plan."

Peter Robinson: "Let's do that.", exactly, right.

Scott Adams: It would be a waste of time, but also it gives targets to the other side. If they want to just criticize what's happening with the administration they don't want to have their own target sitting there that they could fire back. I think that's just the state of politics is that the part out of power is going to look crazy, and confirmation bias and cognitive dissonance and all that stuff is going to be swirling around whichever side is out of power. It's just going to look crazy.

Peter Robinson: Okay. The press. Here's journalist Carl Bernstein of Watergate fame. "We are in the midst of a malignant presidency. It calls on our journalists to do a different kind of reporting." You get a lot of that. In the mainstream media this guy is so bad. This is such uncharted territory for Americans that we have to be advocacy journalism. We have to let Americans know what a catastrophe is. Your advice to the press?

Scott Adams: Keep in mind that the advocates are just advocates, and therefore there's nothing that they say that can be taken with any form of credibility. In other words, they don't even necessarily believe what they're saying. Some of them probably do. I think as soon as you say, "I'm on this team and I'm going to fight till the death", there's no sense of credibility with any of those folks.

Peter Robinson: Okay. Now, your advice for Donald J. Trump himself. He's got an impressive talent stack. You've convinced me of that, but he's also stuck at 40% in the polls. That's where they've peaked. Who knows where he is today, maybe 36%, something like that. Would you keep him from tweeting if you could?

Scott Adams: No way. Tweeting has won him the presidency. It connects him to the people. It makes the people who love him, love him more. He is entertaining. He has made all of us learn more about politics, the law, really just how the world works. We have learned so much, and a lot of it is his direct contact with the people unfiltered, the warts and all. I would take you back a couple years during the campaign when people said, "The one thing we know for sure about Trump is that with this low popularity, he can never win the presidency." I said, "No, you're missing the other way you win the presidency. You don't have to outrun the bear, you have to only outrun your camping buddy. If he can make Hillary Clinton look worse than he looks, doesn't matter how low his number is. He can be a ten if she's a five." What happened? He made her look worse, because he is the best brander, best influencer, best persuader I've ever seen. “Lyin’ Ted”, “Low Energy Jeb”, “Crooked Hillary”, these are not random insults. You saw the other side ...

Peter Robinson: “Low Energy Jeb” ended Jeb Bush's campaign.

Scott Adams: Which I predicted the day I heard it. I said that publicly it's the end of him when nobody was saying that. The reason is his linguistic kill shots, as I call them, are not random. He first of all picks something that fits their physicality. In other words there's a visual element to it.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Scott Adams: The visual is the most persuasive of all. It's the one sense that just overrides all your other stuff. As soon as I heard that I said to myself, "Before I heard that, my impression of Jeb Bush was 'this is a cool, calm, executive. This guy is going to be the perfect guy if there's war. He's not going to get too out of control'". The moment I heard low energy, I couldn't see him any other way. Then every time I saw him the contrast with Trump's high energy just made it all the more damning. By the way, contrast is an enormous thing is persuasion. It's not enough to say, "I'm high energy. I'm high energy." You got to say, "and I'm competing against Low Energy Jeb." That's just deadly. He was done on that day.

Peter Robinson: Scott, a couple of last questions. One question is why do you do what you do. You live in northern California where your views are intensely unpopular. Why do you blog the way you blog? I think I figured it out. You write Dilbert for ordinary Americans. You came from a small town in upstate New York, and yes you got out as fast as you could, you flew to California right away after graduating from college, but still in your mind I think you're a kid from upstate New York, and you don't like getting pushed around. You don't like deferring to experts or authority, and so I think that in some basic way you are as much of a champion of ordinary, overlooked Americans as is Donald Trump.

Scott Adams: I love your version of it. Let me put it in my words. I like to describe a perfect life this way: we're born selfish. A baby can't do anything, right? You have to do something for them. Kids still selfish, but they're learning to do a few things, maybe some errands, some chores. By the time you've got your own kids, you've changed a little bit. You're giving more than you're taking, but you're somewhere in the middle. By the time you're my age, if you've done everything right you have enough for yourself. You've done what you need to do. Finally, you can be mostly a giver. That was always the life arch that I've pursued. Start perfectly selfish and on your last day give it all away. Literally you die, your estate is going. By then, you should've given all of your wisdom, any kindness you had, anything you could contribute. I'm at that stage in my life where that means more to me than money, because I have money, and I have unusually good health for my age. This is how I can give back. When Trump came on the scene what I wrote long before he made a dent in the election, when people still thought he was a joke, I said, "Not only is he going to win at all, but he's going to put a hole in the universe. He's going to change everything about the way you think of your human condition and the way you understand your reality." I thought, "If I'm not explaining this as it happens", because there weren't too many people who could sort of see it from this perspective, "it could be chaos." There could be riots in the streets, which there almost were. When you start seeing this through the filter of persuasion, it makes you feel comfortable that he knows what he's doing, even when he departs from the fact checkers. He says, "fact checking works for you, but I can make it work without that." It's completely intentional.

Peter Robinson: Here's the last question. President Trump in Warsaw earlier this month. "The fundamental question of our time is whether the West has the will to survive. Do we have the confidence in our values to defend them? Do we have the desire and the courage to preserve our civilization in the face of those who would subvert and destroy it?" You and I grew up a couple of counties apart in upstate New York. We're within a couple of months of the same age. What I know about that is it means you can remember the 80s. You can remember the Reagan years. The economy revived. The country recovered its moral. People of our age can actually remember what that felt like. The West won the Cold War. Will the Trump years represent something like that, some kind of national renewal?

Scott Adams: As I predicted that he would win when nobody thought he would, I also predict that he has at least a very high potential to do things in his term the likes of which we haven't seen. For example, I don't think anybody else could solve North Korea. I think he can. Now, I'm going to stop short of saying he can do it, because it's so monstrously difficult, but I think he has the skillset. You saw the way he was dealing with China, because China has to be a part of this. He said, "Hey, China is great. This is your problem in your own backyard. See if you can take care of it. Well, you tried." Look at the level of persuasion that is. People thought, "Oh, that's just a cute tweet. He's just being folksy and stuff.", but the way that paints this picture, it makes China kind of need to step up to the plate. What he said is that you're sort of not the superpower you want to be.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Scott Adams: He basically has challenged them to be the country that they want to be. That's the key. That's how persuasion works. Don't tell somebody to be the way you want them to be. Say, "Look, if you want to be the way you want to be, here's how to get here.", that's very persuasive.

Peter Robinson: Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert, author of many books, including How to Fail at Almost Everything and still Win Big, thank you.

Scott Adams: Thank you.

Peter Robinson: While the camera is still rolling, you have a new book coming out in?

Scott Adams: October, end of October.

Peter Robinson: Entitled How to Win Bigly?

Scott Adams: No, it's just, Win Bigly.

Peter Robinson: Win Bigly. Alright.

Scott Adams: Keeping it simple.

Peter Robinson: We'll do a show on Win Bigly?

Scott Adams: I'd love to.

Peter Robinson: Excellent. For Uncommon Knowledge and the Hoover Institution, I'm Peter Robinson.