- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Economics

In contrast to President Bush’s dark comparison between Iraq and the bloody aftermath of the Vietnam War, there is another, comforting version of the Vietnam analogy that’s gained currency among policymakers and pundits. It goes something like this: after that last helicopter took off from the U.S. embassy in Saigon 32 years ago, the nasty strategic consequences then predicted did not in fact materialize. The “dominoes” did not fall, the Russians and Chinese did not take over, and America remained No. 1 in Southeast Asia and in the world.

But, alas, cutting and running from Iraq will not have the same serendipitous aftermath, because Iraq is not at all like Vietnam.

Unlike Iraq, Vietnam was a peripheral arena of the Cold War. Strategic resources like oil were not at stake, and neither were bases (yes, Moscow did obtain access to Da Nang and Cam Ranh Bay for a while). In the global hierarchy of power, Vietnam was a pawn, not a pillar, and the decisive battle lines at the time were drawn in Europe, not in Southeast Asia.

The Middle East, by contrast, was always the “elephant path of history,” as Israel’s fabled defense minister, Moshe Dayan, put it. Legions of conquerors have marched up and down the Levant, and from Alexander’s Macedonia all the way to India. Other prominent visitors were Julius Caesar, Napoleon, and the German Wehrmacht.

This is not just ancient history. Today, the greater Middle East is a cauldron even Macbeth’s witches would be terrified to touch. The world’s worst political and religious pathologies are combined with oil and gas, terrorism, and nuclear ambitions.

In short, unlike yesterday’s Vietnam, the greater Middle East (including Turkey) is the central strategic arena of the twenty-first century, as Europe was in the twentieth. This is where three continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa—are joined. So let’s take a moment to think about what would happen once that last Black Hawk took off from Baghdad International.

THE DAY AFTER TOMORROW

Iran advances to No. 1, completing its nuclear arms program undeterred and unhindered. America’s cowed Sunni allies—Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the oil-rich “gulfies”—are drawn into the Khomeinist orbit.

You might ask, wouldn’t they converge in a mighty anti-Tehran alliance instead? Think again. The local players have never managed to establish a regional balance of power; it was always outsiders—first Britain, then the United States—that chastened the malfeasants and blocked anti-Western intruders like Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia.

With the United States gone from Iraq, emboldened jihadist forces shift to Afghanistan and turn it again into a bastion of Terror International. Syria reclaims Lebanon, which it has always labeled as a part of “Great Syria.” Hezbollah and Hamas, both funded and equipped by Tehran, resume their war against Israel. Russia, extruded from the Middle East by adroit Kissingerian diplomacy in the 1970s, rebuilds its anti-Western alliances. In Iraq, the war escalates, unleashing even more torrents of refugees and provoking outside intervention, if not partition.

Now let’s look beyond the region. The Europeans will be the first to revise their romantic notions of multipolarity, or world governance by committee. For worse than an overbearing, in-your-face America is a weakened and demoralized one. Shall Vladimir Putin’s Russia acquire a controlling stake? This ruthlessly revisionist power wants revenge for its post-Gorbachev humiliation, not responsibility.

China with its fabulous riches? The Middle Kingdom is still happily counting its currency surpluses as it pretties up its act for the 2008 Olympics, but watch its next play if the United States quits the high-stakes game in Iraq. The message from Beijing might well read, “Move over, America: the Western Pacific, as you call it, is our lake.”

Europe? It is wealthy, populous, and well ordered. But strategic players those 27 member-states of the European Union are not. They cannot pacify the Middle East, stop the Iranian bomb, or keep Putin from wielding gas pipelines as tools of “persuasion.” When the Europeans did wade into the fray, as in the Balkan wars of the 1990s, they let the U.S. Air Force go first.

THE UPSIDE

The United States may have spent piles of chips foolishly, but it is still the richest player at the global gaming table. In the Bush years, the United States may have squandered tons of political capital, but then the rest of the world is not exactly making up for the shortfall.

Nor has the United States become a “dispensable nation,” a most remarkable truth in these trying times. Its enemies from Al-Qaeda to Iran—and its rivals from Russia to China—can disrupt and defy, but they cannot build and lead.

For all the damage to Washington’s reputation, nothing of great import can be achieved without, let alone against, the United States. Can Moscow and Beijing bring peace to Palestine? Or mend a global financial system battered by the subprime crisis? Where are the central banks of Russia and China?

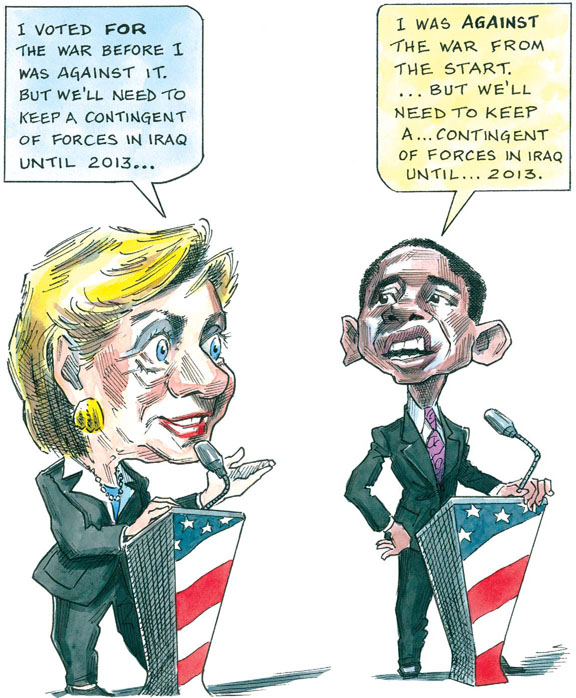

The Bush presidency will soon be on the way out, but America will not. This truth has recently begun to sink in among the major Democratic contenders. Listen to Hillary Clinton, who would leave “residual forces” to fight terrorism. Or to Barack Obama, who would stay in Iraq with an asyet- unspecified force. Even the most leftish of them all, John Edwards, would keep troops around to stop genocide in Iraq or to prevent violence from spilling over into the neighborhood. And no wonder, for it might be one of them who will have to deal with the bitter aftermath if the United States slinks out of Iraq.

These realists have it right. Withdrawal cannot serve America’s interests on the day after tomorrow. Friends and foes alike will ask: if this superpower doesn’t care about the world’s central and most dangerous stage— what will it care about? America’s allies will look for insurance elsewhere. And the others will muse, if the police won’t stay in this most critical of neighborhoods, why not break a few windows, or just take over? The United States as “Gulliver Unbound” may have stumbled during its “unipolar” moment. But as a giant with feet of clay, it would do worse—and so would the rest of the world.