- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

How long, O God, shall men be ridden down,

And trampled under by the last and least of men?

The nineteenth-century poet Alfred Tennyson could not watch video clips on YouTube of Poland’s uprising being crushed, but his response perfectly captures the sense of impotent rage one felt as Burma’s peacefully protesting monks and nuns were beaten up and teargassed by the country’s security forces. It has been 20 years since Burma’s first great movement for democracy in 1988, and 18 since Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy won a clear popular mandate in free elections. Yet under its Orwellian military regime, this beautiful land has sunk even further into poverty and oppression. How long, O God, how long?

As I write in early November, Burmese monks have once again returned to the streets, for the first time since September’s bloody government crackdown. We do not know whether the protests will persist or again be crushed. But two things are clear. Although the minister for religious affairs, General Myint Maung, rails against “external and internal destructionists” and the sinister role of “global powers who practice hegemonism,” the protests of the past few months have been entirely homegrown. After sharpprice rises in August, the cup of bitterness overflowed. No one in Washington, London, or anywhere else outside Burma turned a tap. And this homegrown popular protest has—so far—been as peaceful as can be.

A joint statement from the All Burma Monks Alliance and the 88 Generation Students group, issued at the height of the September protests, began with a remarkable sentence: “The entire people led by monks are staging a peaceful protest to be freed from the general crises of politics, economics and society by reciting the Metta Sutra.” The Metta Sutra reflects on the Buddhist virtue of metta, or unconditional love and kindness. (“This is what should be done/By one who is skilled in goodness,/And who knows the paths of peace.”) One demonstration banner read: “Love and kindness must win over all.”

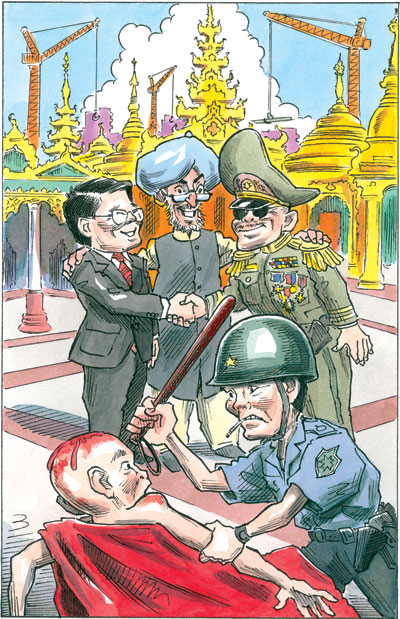

China says it wants “stability” in Burma, and seems to be concluding that stability requires change. But reform sparked by street protests is not the kind that aging communist rulers are keen on.

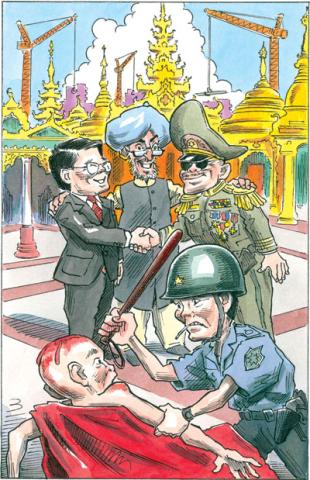

Who was not moved by those video clips, Internet-streamed from digital cameras and mobile phones, showing the rhythmically striding monks and nuns, in their maroon, pale pink, and saffron robes? And by that one grainy snapshot of Aung San Suu Kyi praying at her gate in the pouring rain as the monks strode past chanting, “Long life and health to Aung San Suu Kyi, may she have freedom soon!” It was to this that the supposedly Buddhist generals, who often parade their piety in the Pravda-like pages of the New Light of Myanmar, responded with gunfire, baton blows, and tear gas. In effect, they were beating up the Buddha.

Tennysonian hand-wringing won’t help the people of Burma. So what is to be done? For a start, as many of the world’s leaders as possible should condemn the violent repression.

An old debate has flared up again about the relative merits of a tough policy of isolating the military regime with sanctions, as opposed to a policy of “constructive engagement.” We probably could have done more in recent years to engage with civil society in Burma and to show the generals and colonels the advantages of coming out of isolation. In the longer term, they do need to understand that negotiating with Aung San Suu Kyi and other opposition leaders, and opening up to the outside world, would bring immense benefits to their country. They also need to know that it would not result in them ending up hanging from lampposts or sitting in prison. As Aung San Suu Kyi told me when we talked in Rangoon some years ago (when it was still possible to meet with her), they might even be reassured that they could keep at least some of what she nicely called their “ill-gotten gains.” A change of junta supremo from the aged and obdurate general Than Shwe would be a good occasion for restarting that conversation. But such a policy of encouraging peaceful transition by constructive engagement is not something for the short term. First, we need to stop the junta from killing any more peaceful protesters.

President Bush has announced tighter sanctions to prevent the generals and their families from traveling to or holding assets in the United States— a sanction the European Union has had in place for years. An experienced observer who knows the mentality of the Burmese military—call it superstitious or devout, according to taste—suggests that a far more effective sanction would be for someone to persuade them that beating up monks will result in very bad karma for themselves, their families, and their country. That is not, however, a message that one can imagine a Western leader such as Gordon Brown conveying. It requires not a son of the manse but a priest of the pagoda.

The supposedly Buddhist generals, who often parade their piety in the Pravda-like pages of the New Light of Myanmar, have responded with gunfire, baton blows, and tear gas. In effect, they are beating up the Buddha.

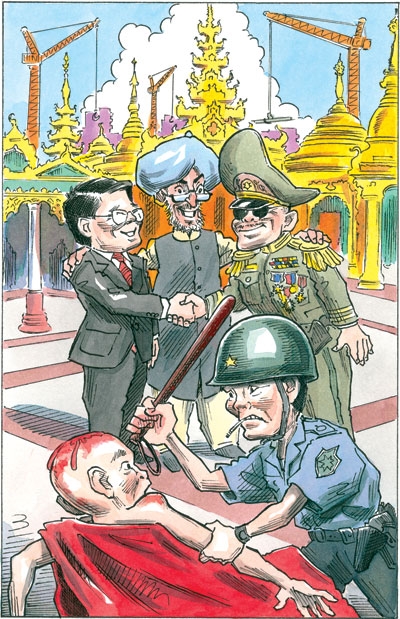

Altogether, there is frustratingly little that Western powers can achieve on their own. But even the European Union and the United States acting together in perfect harmony will make little difference unless Burma’s Asian neighbors start speaking up. Everyone now looks to China, the biggest neighbor with the biggest involvement in Burma. China says it wants “stability” in Burma. Certainly it does not want a bloodbath threatening its business interests there and spoiling the run-up to the Beijing Olympics. Of late, there have been small signs that China is concluding that stability in Burma requires change. But change kick-started by street protests is not the kind that aging communist rulers are keen on.

Too little attention is being paid to Burma’s other big Asian neighbor, India. Although it is the world’s largest democracy, India has so far been pusillanimous in its relations with Burma’s dictators. It seems more concerned about competing for influence (and energy contracts) with China than it is about the nature of the regime. As a result, Burma’s rulers have been able to play India off against China and vice versa. One thing the United States and the European Union could do is suggest, emphatically, to our Indian friends that this is shortsighted. Ideally, India and China would also get together to see if they have common as well as competing interests in the unhappy land sandwiched between them. Two giants should not be played off so easily by a pygmy.

None of this seems likely to stop the generals from clamping down again, but there is still a chance their repression won’t succeed. History is always open. And even if this round of protests is suppressed, the world will have been dramatically and movingly alerted to Burma’s plight; Burma’s Asian neighbors will have been shaken out of their sluggish passivity; and we can hope that Burma’s nonviolent opposition will itself learn something from the experience, something for next time. If so, the monks will not have marched in vain.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in the Guardian (U.K.) on September 27, 2007.