RIGA, LATVIA—Undeniably, the project of building liberal democracy in Central and Eastern Europe since the end of the Cold War has been a resounding success. But the purpose of this international gathering in Latvia’s capital this February, which drew a high-powered congressional delegation led by Senator John McCain, was not to celebrate success but to draw attention to one conspicuous failure: Europe’s last dictator, Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus.

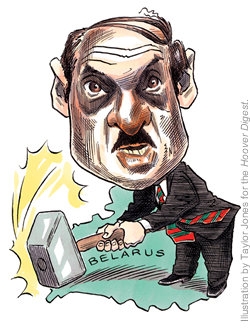

Belarus, a former Soviet republic of 10 million people bordering NATO members Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia, has since independence largely remained the domain of its former communist leaders. Lukashenko became president 10 years ago and moved swiftly to consolidate his hold on the country, closing newspapers, jailing opposition figures, granting broad powers to his intelligence service (the BKGB), and arranging for his 2001 re-election by means neither free nor fair. His ambition went so far as to imagine himself the supreme leader of a reunified Russia-Belarus, a prospect that, fortunately, now looks remote—for reasons having nothing to do with any newfound moderation on Lukashenko’s part. Meanwhile, he has driven Belarus’s economy straight down, a fact especially noteworthy by contrast with the success of Belarus’s Baltic neighbors, which began the post-Soviet period with no great special advantages over Belarus.

Lukashenko’s methods are brutal. Last year, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe authorized an investigation into the disappearance of several prominent Belarus opposition figures. The rapporteur’s report, released in late January, pointed straight to the top: “In view of the seriousness of the facts established so far and the grave suspicions arising from these facts against senior government officials, and even President Lukashenko himself, I consider it necessary to send a strong signal to the Belarussian regime.”

Parliamentary elections in Belarus are scheduled for October. Once again, there is no reason to expect Lukashenko to organize anything but a sham. This time, however, it looks like he may face a challenge he hasn’t had to contend with before: a united opposition. The quarreling among opposition factions made it easier for Lukashenko to contend that they were responsible for their own defeat, notwithstanding his cheating. At the Riga conference, titled “The Future of Democracy beyond the Baltics,” leading opposition figures came forth to tell their stories and to pledge their willingness to work together.

The most urgent task has been to draw up a single list of opposition candidates for the parliamentary elections. More broadly, the opposition must develop a reform agenda that will appeal to voters who have been relentlessly propagandized by the Lukashenko government and fear the loss of the meager pensions and wages they currently receive.

There is little doubt but that Lukashenko will do whatever he must in order for his followers to “win” the parliamentary elections. The key point is that with a united opposition, he will have to be much more blatant in doing so, which in turn will expose him to local and international pressure. On the latter score, the nations of northern Europe, especially, have committed themselves to working together to keep the pressure on Lukashenko. The European Union, cognizant of the danger that will be on its own border once the European Union expands to Poland and the Baltics in May, is also likely to increase its attention to Belarus. Another consideration, and no small one, is that the United States and Europe are in fundamental accord on Belarus, which positions them to present a united front against Lukashenko.

With hard work and good luck, the pressure will be too much for Lukashenko to grant himself a third term in the presidential election scheduled for 2006. And that in turn will put to rest any notion that he is developing a useful model for others to follow in maintaining their hold on power through repressive measures.

The Riga conference featured an especially moving speech by Irina Krasovskaya, whose husband, a prominent businessman who helped fund the democratic opposition, disappeared along with another opposition leader in September 1999. Presumed dead, their cases were among the ones examined by the Parliamentary Assembly rapporteur. Krasovskaya is considered by one prominent member of the delegation as a potential Corazon Aquino, the widow-by-assassination around whom Filipinos united to pressure Ferdinand Marcos out of office in 1986. As Krasovskaya noted, the path to the end of Lukashenko’s tyranny and success for democracy in Belarus calls for “the United States and Europe behind us and a united opposition in front of us.” That’s a challenge but a manageable one. It’s certainly one worth rising to for the sake of Belarus and to banish dictatorship in Europe once and for all.