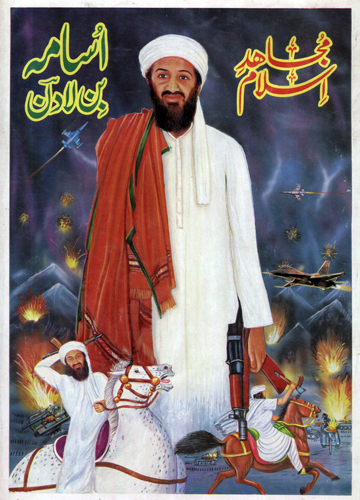

What do jihadists want? Simple: power. The power to impose their own extreme version of Shari’a law. But that is not what most Muslims want. For the most part they want the same things as non-Muslims: jobs, education, families, a higher standard of living, peace, and security. Therein lies both the power and the weakness of jihadist extremists: they are strong because they are motivated by religious certitude, but at the same time they are weak because their program is too austere to be popular when actually implemented even in traditional Muslim societies. If properly exploited by a skilled adversary, this weakness can turn out to be fatal.

Both the appeal and the limitations of jihadism have been evident in one of the longest-running guerrilla struggles of the past two centuries—the movement by the people of Chechnya, Dagestan, and other parts of the Northern Caucasus to free themselves from Russian imperial rule. The struggle started in the 18th century and continues into the 21st century. But it was in the 19th century that it produced its most notable personality—a forerunner of Osama bin Laden and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi known simply as Shamil.

Born in 1796, Shamil became imam of the gazavat (holy war) against the Russians in 1834 after his predecessor as imam was assassinated by tribal rivals. A skilled horseman, sword fighter, and gymnast, Shamil cut an impressive figure, standing six feet three inches and appearing taller still because of his heavy lambskin cap, the papakh. His flowing beard was dyed orange with henna, and his face was, in Tolstoy’s telling, “as immovable as though hewn out of stone.” His force of personality was such that one of his followers said that “flames darted from his eyes and flowers fell from his lips.”

To keep a desperate resistance going against overwhelming odds required the ability not only to inspire hope but also to instill fear. Shamil was a master of both. He traveled everywhere with his own personal executioner, chopping off heads and hands for violating the dictates of Allah and his humble servant, the Commander of the Faithful in the Caucasus. Although he was influenced primarily by the Sufist tradition, Shamil’s “fanatical puritan movement,” notes one history book, “was in many ways comparable to the contemporary Wahhabi movement in Arabia.” He did not hesitate to slaughter entire aouls (villages) that did not heed his demands.

When a group of Chechens, hard-pressed by the Russians, sought permission to surrender, they were so afraid of his wrath that they conveyed their request through Shamil’s mother, thinking this would make him more amenable. Upon hearing what she had to say, Shamil announced that he would seek divine guidance to formulate an answer. He spent the next three days and nights in a mosque, fasting and praying. He emerged with bloodshot eyes to announce, “It is the will of Allah that whoever first transmitted to me the shameful intentions of the Chechen people should receive one hundred severe blows, and that person is my own mother!” To the astonished gasps of the crowd, his followers, known as the murids (“he who seeks” in Arabic), seized the old lady and began beating her with a plaited strap. She fainted after the fifth blow. Shamil announced that he would take upon himself the rest of the punishment, and ordered his men to beat him with heavy whips, vowing to kill anyone who hesitated. He absorbed the ninety-five blows “without betraying the least sign of suffering.” Or so legend had it.

This street theater helped animate Shamil’s murids to maintain a fierce resistance. He mobilized over ten thousand men to conquer much of Chechnya and Dagestan and inflicted thousands of casualties on Russian pursuers. But over time, his ruthlessness cost Shamil popular support—as it did for more recent Chechen rebels. Tribal chieftains who did not want to cede authority to this religious firebrand turned for support to the Russians. So did many ordinary villagers who balked at his demands for annual tax payments amounting to 12 percent of their harvest.

Russia’s initial response to the Chechen uprising in the 19th century—as in the 21st century—was characterized by brute repression. One early Russian viceroy, General Alexei Yermolov, said: “I desire that the terror of my name should guard our frontiers more potently than chains or fortresses…. One execution saves hundreds of thousands of Russians from destruction, and thousands of Mussulmans from treason.” But the scorched-earth approach Yermolov practiced drove more recruits into the murids’ camp. The Russians only began to have success against Shamil when they launched efforts to woo the population away from the Islamists.

The turnaround began when Prince Alexander Bariatinsky took over as viceroy of the Caucasus in 1856, following the accession of his childhood friend as Tsar Alexander II. In contrast to his reactionary predecessor, Nicholas I, the new tsar was a modernizer and a liberal. He encouraged Bariatinsky to try a more conciliatory approach. Whereas Shamil traveled with his executioner, Bariatinsky traveled with his treasurer, doling out bribes to tribal leaders. Those elders also received more autonomy within the imperial system and protection from the fanatical murids. “I restored the power of the khans as a force inimical to theocratic principle,” Bariatinsky explained. (Gen. David Petraeus did much the same thing in Iraq where he recruited Sunni sheikhs to oppose al-Qaeda in Iraq.) In addition, Bariatinsky encouraged Muslim clerics to denounce Shamil as an apostate and to preach a doctrine of nonviolence.

To address local grievances, he issued orders to allow women and children to escape from besieged aouls instead of simply killing everyone as in the past. He even sponsored greater educational opportunities for women. “I believe it is important,” Bariatinsky wrote, “to win the greatest possible devotion of the territory to the government, and to administer each nationality with affection and complete respect for its cherished customs and traditions.”

Like all great counterinsurgents, even the most liberal, Bariatinsky did not limit himself to such “hearts and minds” appeals. He undertook large-scale clear-cutting of forests to flush out the rebels, and he built bridges to reach their mountain aeries. He also issued his soldiers rifled weapons, which were considerably more effective than the flintlocks employed in the past. Rather than undertake futile punitive expeditions, he launched a systematic reduction of all rebel strongholds in Dagestan.

The final push began in 1858 with three armies converging on the rebels’ fortresses. Shamil’s aeries fell one after another until finally he was left with just 400 followers in the aoul of Gunib facing an army of 40,000. Seeing the hopelessness of the situation, Shamil surrendered on August 25, 1859. He pledged allegiance to the tsar and urged his followers to lay down their arms, and in turn he was well treated. Shamil lived out his days in Russia with the benefit of a pension and country house provided by the tsar. He finally died in 1871 while making the Hajj to Mecca in Ottoman-controlled Arabia.

This enlightened approach to counterinsurgency—which blended carrots and sticks—stands in stark contrast to the more brutal approach employed by Stalin in the 1940s to put down another Chechen uprising. The Soviet dictator deported half a million Chechens and Ingushes (another ethnic group in the North Caucasus) to Central Asia, killing tens of thousands along the way. The Chechens were only allowed to return following Stalin’s death.

Much has changed since Stalin’s day, but the Russian army’s approach to pacification in Chechnya in recent years bears more resemblance to his tactics (and Yermolov’s) than Bariatinsky’s. After Chechnya’s declaration of independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russians invaded Chechnya in 1994 and pulled out in 1996, stymied by Chechen guerrillas who, like their nineteenth-century predecessors, resisted to the death. But the Russian army returned in 1999 to subdue the breakaway province using scorched-earth tactics. The capital, Grozny, was leveled. An estimated 100,000 Chechens were killed out of a prewar population of just a million; perhaps 20,000 Russian soldiers also perished.

At first a purely nationalist uprising, the Chechen resistance assumed more of a jihadist character as the conflict went along. But, just as in the days of the original Shamil, no amount of faith could enable Shamil Basayev (a fanatical Islamist leader who was killed in 2006) to prevail. In fact the extremism of the new Shamil and his confederates backfired, just as it did for their nineteenth-century forerunner. The Chechen rebels sacrificed any goodwill around the world with heinous acts of terrorism such as the taking of hostages in a Moscow theater in 2002 (at least 170 people died when Russian commandos stormed the building) and at a middle school in North Ossetia in 2004 (380 people died, at least half of them children).

Chechnya now has a measure of stability, but it still chafes under the heavy-handed and corrupt rule of a Russian puppet regime—and resistance, in the form of acts of terrorism in the Northern Caucasus and southern Russia, continues. Nothing can excuse the attacks of Chechen terrorists, but nor is there any excuse, either morally or strategically, for the human-rights abuses committed by the Russians and their proxy forces. There will be no lasting peace in the Caucasus until Vladimir Putin stops practicing Yermolov-like brutality and instead adopts a more measured, Bariatinsky-style approach to pacification.

The U.S., too, should heed the lessons of nineteenth-century Chechnya in its battles against jihadists around the globe: While hard-core terrorists need to be captured or killed, the long-term key to victory lies not in meting out death and destruction but in making common cause with Muslim moderates against the extremists who seek to dominate their societies.