On January 24, 2013, Leon E. Panetta, then Secretary of Defense, and Army General Martin E. Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of State, signed a memorandum rescinding the 1994 ban on women serving below the battalion level and eliminating the remaining sex-based restrictions throughout the services. Panetta’s rationale was lofty: “If members of our military can meet the qualifications for a job…then they should have the right to serve, regardless of creed or color or gender or sexual orientation.” His rationale was also practical: “Female service members have faced the reality of combat, proven their willingness to fight and, yes, to die to defend their fellow Americans.” Prior to this announcement, the Joint Chiefs of Staff unanimously endorsed allowing women to serve on the front lines. The decision is intended to be operational by 2016.

In the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars, approximately 300,000 women have served in or near combat zones, more than 150 have died as a result of combat or noncombat factors, and nearly 1,000 have been wounded. Furthermore, approximately 14 percent of the 1.4 million active-duty U.S. military personnel are women.

Neither these statistics nor these lofty goals for a gender-neutral military are sufficient reasons for rescinding the 1994 ban on women in combat. Historical trends and America’s founding ideas suggest a more powerful case.

Women have been an integral part of every war in U.S. history. Women worked alongside their husbands, sons, and brothers in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, typically serving in support capacities, although some disguised themselves as men in order to fight. Others served as spies or couriers. In the Spanish-American War of 1898, 1,500 women served.1

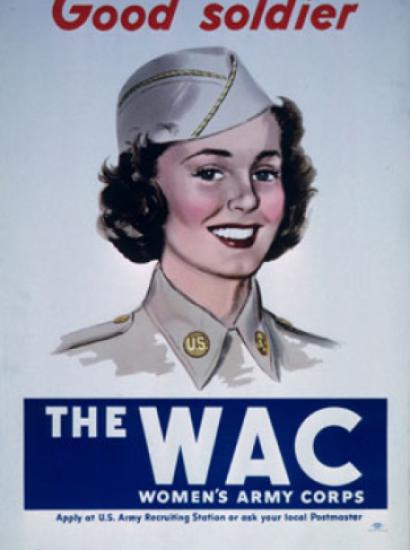

Women formally became part of the U.S. military in 1901 with the creation of the Army Nurses Corps, and more than 10,000 US women joined World War I, serving primarily as nurses. In World War II, 400,000 women served in nursing, administrative, and other capacities. Recognizing the importance of women’s roles in the deadliest war in history and their subsequent military service, Congress legislated in 1948 that women would become part of the permanent military. Thousands of women served in the wars in Korea and Vietnam. Women have died in all of these wars.

Major changes to the status of women in the military occurred in the 1970s. Among numerous distinctions, a woman finally attained the two-star rank, women were accepted into the service academies, and a woman was selected to be a military chaplain.2

The 1988 “risk rule” prohibited women from serving in noncombat roles that would put them in the line of fire or expose them to situations that could lead to their capture. Secretary of Defense Les Aspin revoked the rule in 1994, but he also oversaw a policy mandating that “service members are eligible to be assigned to all positions for which they are qualified, except that women shall be excluded from assignment to units below the brigade level whose primary mission is to engage in direct combat on the ground.”3

The risk rule was rendered invalid due to battlefield realities. In the Gulf War of 1990-91, everyone in or near combat zones was inherently at risk. Fine lines of demarcation that were extremely difficult to draw are now often impossible to discern in the counterinsurgency and asymmetrical wars waged post-9/11. Men and women who join the U.S. military to serve in the theater of war in the twenty-first century must know that they will face complex challenges on an amorphous and unpredictable battlefield that bears little resemblance to combat zones of the past. The newest Pentagon decision on women in the military reflects this reality. What constitutes the battleground in a counterinsurgency war like the one in Afghanistan? Aren’t medical staff members and intelligence officers as much at risk as soldiers? Women have been on patrols with ground troops in Afghanistan. They have also been indispensable in meeting with Afghan women as the International Security Assistance Force implements confidence-building measures among civilians.

In its final report of March 15, 2011, the Military Leadership Diversity Commission recommended allowing women to serve in combat roles on these grounds: “Given the nature of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, women are currently engaged in direct combat, even when it is not part of their formally assigned role.”

The service of women on the front lines is as important for the American Creed as it is for battlefield realities. The American Creed, encompassing the concepts of equality of all, liberty, individual rights, property rights, and democracy, forms the basis upon which U.S. political institutions and the Constitution are built and, indeed, has provided justification for U.S. entry into some of the world’s bloodiest wars. In order to survive as a democratic nation, the United States must ensure that its political institutions come into alignment with the ideas put forth by the Founding Fathers. Allowing women to serve in the armed forces at every level is simply one more means of cementing these ideas into institutions that are inherently brittle.

1. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, America’s Women Veterans: Military Service History and VA Benefit Utilization Statistics (Washington, DC: National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, Department of Veterans Affairs, November 2011).

2. John H. Cushman Jr., “History of Women in Combat Still Being Written, Slowly,” New York Times, February 9, 2012.

3.http://big.assets.huffingtonpost.com/irectGroundCombatDefinitionAndAssignmentRule.pdf