- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

The Iran nuclear deal makes an Israeli strike less likely in the near term, and more likely in the medium term unless U.S. policy changes to restore the credibility of our own military options and suppresses the non-nuclear threats Iran is fomenting.

From the very beginning of the Obama Administration, there was a clear strategy for dealing with Iran: restrain the Iranian nuclear weapons program by multilateral agreement. President Obama’s policy consisted of further tightening multilateral sanctions on Iran, and subordinating all other issues to the objective of attaining a nuclear deal.

The Iran deal to some extent does restrain Iran’s nuclear weapons programs by establishing international monitoring of known Iranian nuclear facilities. But among the many reasons for skepticism about the agreement is that we are unlikely to know the extent of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure. Another important reason for skepticism is that Iran reaps the benefits of sanctions relief at the beginning of the process, which removes incentives to remain in compliance. The “snap back” sanctions provisions require consensus among the signatories, which means little short of a nuclear weapons test—or use—would be sufficient.1

Moreover, initial enforcement strongly suggests leniency: since the agreement entered into force, the U.S. and other parties to the agreement have permitted Iran leeway in compliance. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reported Iranian low-enriched uranium in excess of treaty allowances, and more radiation containment chambers than listed in Iran’s declaration; the governments of the U.S., UK, France, Germany, China, and Russia allowed the treaty to enter into force anyway.2 More recently, Iran was found to be making centrifuge parts restricted by the deal. The IAEA nonetheless concludes that Iran has engaged in no significant violations of the agreement.

The agreement probably includes a sufficient mix of inspection and incentive to prevent any overt and militarily significant Iranian non-compliance in the near-term, given the economic privation that drove Iran to the negotiating table. But it absolutely has not inhibited Iran behaving provocatively: it has accelerated its ballistic missile programs, harassed U.S. naval vessels in the Straits of Hormuz, and engaged in dangerously reckless rhetoric, threatening to shoot down U.S. vessels operating in international airspace. Iran has increased, not decreased, its provocations since the signing of the nuclear agreement.3

The narrow focus on Iran’s nuclear weapons programs ignores the many other threats Iran is posing: (1) terrorism—including attempting to assassinate the Saudi ambassador in Washington; (2) destabilizing neighboring states by aggravating sectarian tensions in Iraq and Bahrain, and arming insurgent groups like Hezbollah and Hamas; (3) disruption in the Straits of Hormuz by laying mines and harassing naval vessels operating in concordance with international maritime practice; and (4) ballistic missile attacks on neighboring countries.4

The principal mistake of the Obama Administration’s Iran deal was dealing only with the threat posed by a nuclear-armed Iran. We have not sufficiently addressed the non-nuclear security concerns of Israel, the UAE, and other Gulf Cooperation Council countries. In fact, the drumbeat of Obama Administration policy choices in the Middle East have alarmed our friends: withdrawing from Iraq in 2010 when the insurgency had been beaten back and Iraqis voting for multi-sectarian political slates, disparaging the value of military force against Iran’s nuclear facilities and more generally to influence political choice by adversaries, declining to trust our allies with details of the Iran negotiations while they progressed, failing to enforce the red line in Syria, accepting Russia’s intervention to bolster the Assad regime in Syria, and now becoming complicit in atrocities by Syria and Russia through our latest agreement.

It is the breadth of policy failure that has pushed our partners in the region into considering acting without American support. Saudi Arabia and Israel have never been closer in their security cooperation; neither have they been further from us (despite arms sales). If the United States cannot be relied upon to enforce the Iran agreement and attenuate the threats Iran poses, Israel may be forced to act in the medium term. The relationships being fostered among our allies in the Middle East will facilitate any Israeli military action—whether against Iran’s nuclear facilities, or other targets selected to signal that whatever the U.S. won’t do, Israel is not likewise constrained. Only a more assertive U.S. policy changing attitudes in the Middle East about our willingness to stop Iran’s expanding influence will suffice.

1Hoover’s George P. Shultz and Henry Kissinger produced the most compelling indictment of the agreement in “The Iran Deal and Its Consequences,” The Wall Street Journal (April 7, 2015).

2Jonathan Landay, “U.S., others agreed ‘secret’ exemptions for Iran after nuclear deal: think tank,” Reuters (September 9, 2016).

3George Jahn, “UN nuclear report notes Iran is making sensitive parts,” The Washington Post (September 9, 2016).

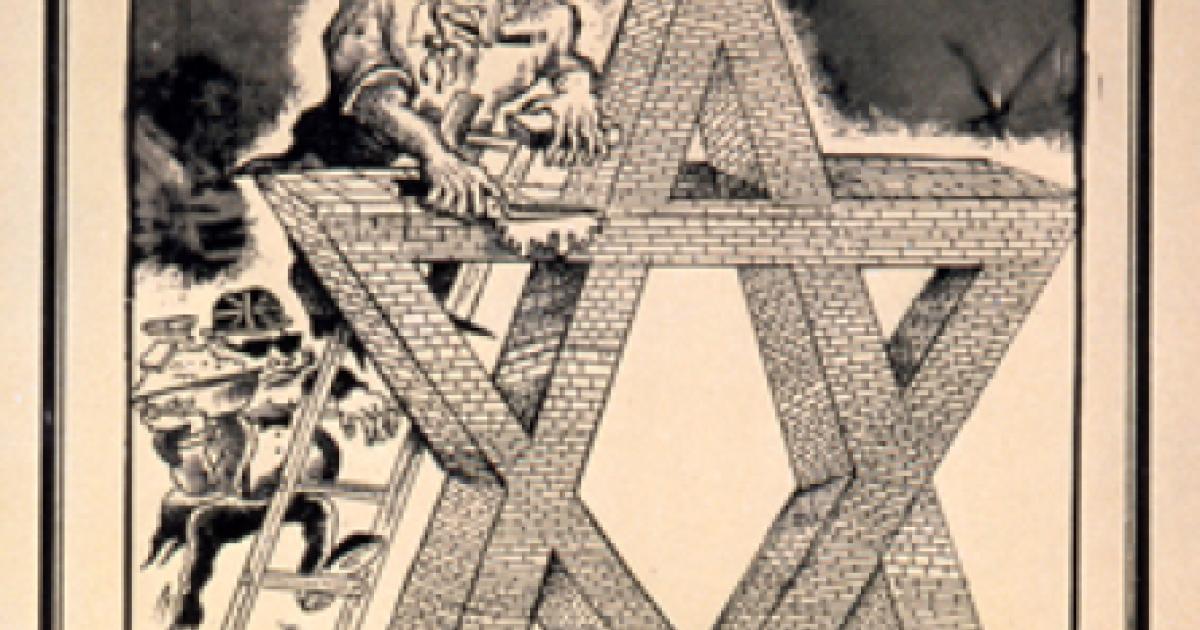

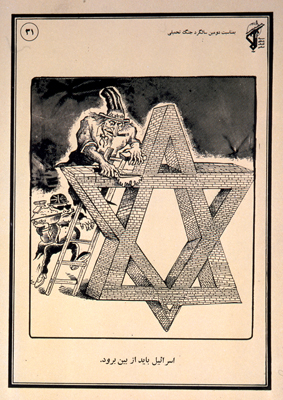

4Recall the recent missile test with “Israel must be wiped out” painted on the missile: Julian Robinson, “‘Israel must be wiped out’: Iran launches two missiles with threat written on them in Hebrew as country ignores criticism of its ballistic weapon tests,” Daily Mail (March 9, 2016).