- Economics

- Contemporary

- International Affairs

- History

Moscow evokes a variety of images in the West: the onion-domed churches of the medieval Kremlin; stolid Soviet leaders reviewing military parades in Red Square; the glitzy wealth of the post-Soviet elite; the macho self-presentation of Vladimir Putin. But images change much more slowly than realities. The incredibly deep, efficient, and loud subway system is still there. The Stalinist wedding-cake skyscrapers still dominate the skyline. There are still too many restaurants and nightclubs that far too few people can afford and horrendous traffic that is daunting for even the most experienced drivers. But Moscow has changed. It has become—almost—a normal European capital.

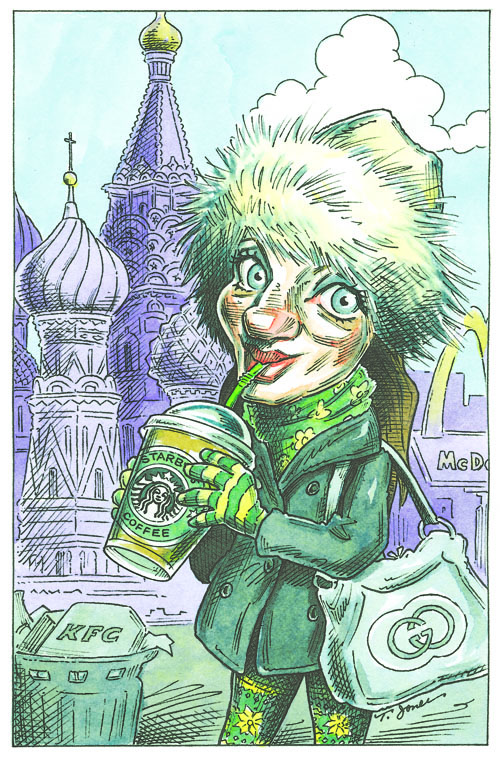

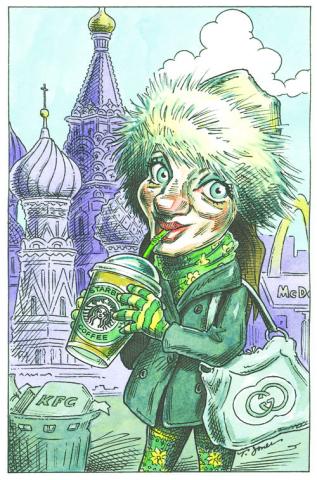

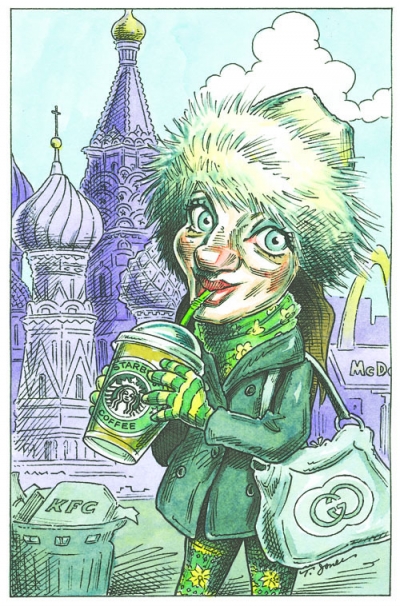

I have been a regular visitor to the city for over forty years. I asked myself why, during a research trip last summer, I felt—for the first time, really—pretty much at home. I think the basic reason is that the Russian capital has become much more Europeanized. A plethora of interesting and reasonably priced restaurants and coffeehouses have popped up all around the downtown, and even in some of the more remote districts. There are plenty of fast food places—too many, in fact. In my immediate neighborhood there was a “cute” Georgian restaurant; an interesting courtyard cafe with a ceiling of open umbrellas (it showed art films, too); a delicious Uzbek restaurant; and a Thai place. Not only was the food good and genuinely “ethnic,” but the prices were reasonable, at least by the standards of most European metropoles, something relatively new to Moscow in the post-Soviet period.

My old-fashioned Soviet apartment did not have wi-fi, so I headed out after work to the coffeehouses, a different one almost every evening, and all with wireless Internet connections. Starbucks was everywhere, of course, as in any other European capital, but I was impressed by the variety of other shops selling coffee, tea, and pastries. Other urban amenities abound: a quick train ride from the subway system to the international airport; public bathrooms (though not enough of them); better street signage; Internet cafes; and computer services in the post offices.

Also, people were mostly (one wouldn’t want to go overboard) friendly, nice, and helpful in public places. For anyone who had been to Russia during the Soviet period, the previous sentence might seem laughable. In Soviet times, Russians were generous and hospitable in their homes, but absolutely stone-faced on the streets, where Hobbes’s state of nature ruled. That has changed gradually since the end of the Soviet period. But this was the first time people actively helped me: dealing with punching the tickets on the trolleybus; finding my way when I was looking at a map; sorting unfamiliar coins; getting off at the right train stop while coming home from a visit to a friend’s dacha. In the cafeteria of the archives, where I ate lunch every day, the women who worked behind the counter were positively charming, friendly, helpful, even a bit flirtatious. Again, anyone who remembers such institutional cafeterias (stolovaia) from the Soviet period will also remember the intimidating, harsh, and unwelcoming women who worked there, not to mention the unpalatable food. These changing attitudes may have something to do with the volunteerism associated with the flood relief efforts in the Krasnodar region last August. The local government failed its citizens on a number of counts; at the same time, waves of volunteer help, funds, and gifts flowed into the area swiftly and efficiently.

FEWER BODYGUARDS AND HOMICIDAL DRIVERS

I am convinced that street life in Russia has also become markedly more civilized, especially over the past decade. No more does one see armed guards around luxury stores or chauffeurs standing by limousines waiting for their bosses with hands on weapons. After the fall of communism, when Muscovites first started buying cars and driving everywhere, the automobile culture was brutal. You could be run down by drivers who regularly parked their proud new possessions on the sidewalks. Living in Moscow in 2000, I had several near misses crossing the street, where pedestrians had absolutely no rights. There also was a lot of drinking, spitting, and unruly behavior on the streets, day or night. It’s not that Russians have stopped drinking—alcoholism is still a big problem—but street culture has changed markedly for the better, no doubt bolstered by stricter and more enforceable rules for public behavior. Smoking has decreased, and will soon be banned in restaurants, cafes, and other public places. Drivers are driving better and more politely. There are regular pedestrian crossings, which work; drivers will stop to let you cross, even when the crosswalk is not marked. Most astonishing of all, Russian drivers will sometimes motion for you to cross when you make eye contact.

A large and growing workforce of Central Asian immigrants does the work that most Muscovites shun, including keeping the streets and sidewalks clean, dealing with the city’s garbage and (now) recycling bins, and handling a lot of the lower-end service positions. Moscow’s mayor, Sergei Sobyanin, has estimated that about two million illegal immigrants are living in the capital, out of a total population of maybe fifteen million. Others suggest these estimates are exaggerated. The reported unemployment rate for Russians is low, 4.9 percent, the lowest, according to the Financial Times, in a decade. Foreigners are increasingly able to find unskilled construction jobs and other blue-collar work. Many Central Asians, in particular, work in restaurants and cafes; others sell vegetables and fruit in the market stands and low-cost household goods on street corners. There are complaints and worries about the immigrant population, just as in comparable European capitals. Periodically, there are confrontations with right-wing Russian thugs and violence against the “guest workers.” But, on the whole, the newly arrived Central Asians—some know Russian, many do not—have integrated fairly well into the economic life of the city.

Other aspects of contemporary Moscow make it seem like a regular European capital. There is a lot of good music—opera, symphony, ballet—that remains, despite the higher prices, within the means of enough people to fill the concert halls. The museums remain of high quality and easy accessibility. There are fancy shopping centers and low-priced department stores. Numerous dachas for the wealthy are being built or renovated outside the city (some of them resembling small palaces); nearly half the city’s residents have access to some form of dacha during the heat and humidity of summer. Younger people appear relaxed and cool. Young couples are out on the street with their children, something rarely seen even a decade ago. Moscow’s birthrate, in fact, has gone up, defying expectations. Apocalyptic predictions of a decade ago about the rapidly declining Russian birthrate and the high death rate, in particular for men, now seem wildly pessimistic. The rising birthrate indicates Russians’ growing confidence in the world around them and their ability to support a family. At work, too, Russians seem more at ease with themselves and their circumstances. All my friends were more at one with the lives they were living—if not at all with the political system dominating the country—than at any time since the fall of communism.

A MORE PROMISING ECONOMY

Many of the changes come from the development of a real middle class of Muscovites who work in business, education, communications, and even government, who regularly travel abroad, more than ever in the Russian past, and have developed the social and cultural tastes of cosmopolitan European urban dwellers. The garishly dressed men and women of the early post-communist gold rush days have dwindled in comparison to the tastefully attired modern Muscovites, though there are still plenty of diamond-bedecked, mannequin-like blondes and Al Capone doubles hopping out of their chauffeur-driven cars into chic restaurants and nightclubs. The cars still seem bigger and more expensive than need be. There is a stunning attachment to shining new Mercedes-Benzes and BMWs, especially black SUVs. (BMW sales rose at least 30 percent in 2012.) But projected new taxes on bigger vehicles, the planned installation of parking meters, and devastating traffic, will, I suspect, change this automobile landscape as well.

The sense of financial well-being among middle-class Russians may well derive ultimately from petroleum, natural gas, and other resource commodities, but they nevertheless manage to have well-paying jobs in fairly normal institutions. Of course the government, broadly defined, is a huge employer in Moscow. Working in the bureaucracy pays well, and it offers contacts and networks for increasing one’s income in a variety of illegal and semilegal ways. There is still an awful lot of corruption, which everyone recognizes, at least publicly, is hurting business and investment. But it is also true that there is a remarkable growth of well-paying jobs in finance, industry, trade, government, and service industries. This cannot be said for many depressed regions outside the capital.

For the moment there seems to be relative stability in the Russian economy. One cannot say it is going gangbusters, but at roughly 3.5 percent to 4 percent GDP growth and with some problems with inflation, Russia’s economic situation can be seen as comparatively robust when compared with its European counterparts.

Now that Russia belongs to the World Trade Organization, Moscow will become even more like other European capitals. There will be more European food products and problems for Russia’s agricultural economy. Buying European cars will be easier and the Russian automobile industry will face new competition, though tariff barriers do not seem to have hindered Muscovites from buying from the West in any case. Most observers predict that joining the WTO will contribute to a modest growth in trade and commerce that will help attract investment and may even bolster the government’s reform efforts in commercial and financial law. In this sense, the middle class will benefit; its consumer habits—Muscovites rarely save—will continue to be stimulated by new services and products from abroad.

THE REAL ROADBLOCK: THE POLITICAL SYSTEM

The big problem for members of this expanding middle class is the political system. They displayed their expectations in the protests last winter that drew tens of thousands of mostly well-dressed and well-heeled Muscovites after the “re-election” of Vladimir Putin to the presidency. Just as their expectations for urban amenities and their tastes in food, clothes, music, and cars have been shaped by European norms and trends, so too do they expect a political system that allows them to speak, write, read, and vote like their European counterparts, in a democratic and parliamentary system. Instead they have Putin, a combination of would-be dictator and front man for a complex, interconnected network of political and economic oligarchs, whom some have now labeled a new Politburo. The Muscovite middle class, at least a good part of it, is embarrassed by the political system and upset with the murders of opposition journalists, which seem to have abated for the time being, and repeated examples of political repression, which have not.

Putin appears on television almost every night in somewhat different, highly crafted poses: hectoring politicians to do a better job of providing flood relief, enjoining athletes to do their best, mixing with common folk on the street, discussing issues of administrative responsibility with governors or bureaucrats. Unlike the Soviet dictators of the past, Putin is seen very close up. His every gesture, expression, and facial movement seems scripted. His speech is both down to earth and determined, and his control of facts, problems, and events appears real. He’s not the “czar/father” of the imperial period, nor is he Stalin. He is more accessible than either, and his disciplined and forceful mien seems to appeal to Russians, and he knows it. Every poll indicates a high approval rating for Putin, who always outpolls his present prime minister and former president, Dmitry Medvedev, and any potential opposition leader. The demonstrations against Putin and his dictatorial regime have been serious and important, but Muscovite middle-class liberals cannot compete with his appeal to the population as a whole. Not only that, there seems to be no legitimate alternative, either within the government clique or without.

Even the “Pussy Riot” affair indicated that Moscow has become almost a normal capital. The punk-rock feminist group itself could fit in easily in Berlin, Milan, Paris, or Liverpool. Its staged protest in a church, which led to three convictions (one later reduced), could have happened anywhere in Europe. What was unusual, and distinctly not normal for the continent, were the harsh conditions of the trial and detainment and the outrageous sentences to a penal colony, a punishment clearly influenced by the Soviet-style norms of the court, the Orthodox Church, and Putin and his government. Elsewhere in Europe, a night in jail and a fine might have been expected. Muscovites outraged by the sentence were those who feared that their increasingly good lives could be violated by a government insisting on dated judicial norms and behavior. It hurts them to realize that they still live under a form of dictatorship, whose attachment to the rule of law is tenuous and unpredictable.