- K-12

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- Education

The achievement gap between advantaged and disadvantaged children is a consistent concern for those involved in education. Although many attribute the gap to inequalities in resources and poor learning environments at home and at school, data from the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) indicate that low achievement scores are more often related to high rates of school mobility. One explanation for this relationship, according to E. D. Hirsch and others, is the curricular inconsistency in the American educational system.

A common measure of mobility is the percentage of students who have transferred in or out of a school in the past year. Mobility rates range between 45 and 80 percent for inner-city schools and between 25 and 40 percent for suburban schools. Children from low-income families or children who attend inner-city schools are more likely than others to have changed schools frequently, where “changed schools frequently” is defined as third graders who have changed schools three or more times since the first grade. According to the 1994 GAO study,

• About 17 percent of all third graders—more than a half million—have changed schools frequently.

• More than 24 percent of third graders have attended two schools since the first grade.

• Of third graders from low-income families (incomes below $10,000), 30 percent have changed schools frequently, compared with approximately 10 percent from families with incomes of $25,000–$49,000 and 8 percent of children in families with incomes of $50,000 or more (see figure 1).

• About 25 percent of third graders in inner-city schools have changed schools frequently, compared with about 15 percent of third graders in rural or suburban schools.

|

Of the many factors that contribute to high rates of mobility in inner-city areas, three stand out: family income, population density, and home ownership. The home environments of children from low-income families are not as stable as those of families with higher incomes. In lower-income families, the rates of illegitimacy, divorce, and single-parent households are higher and there is a greater dependence on the extended family to provide care and housing for children. This means that low-income children are shuttled from house to house more often than those from high-income families.

With lower population densities, suburban school districts often cover larger geographic areas than do inner-city districts. Whereas a move within the inner city almost assuredly requires a change of school, a move of equal distance in a suburban district is much less likely to require a school transfer.

Home ownership affects school mobility because renters are more common in urban areas and tend to move much more frequently than do home owners. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1999, 35 percent of renters had moved within the last year, compared with only 8 percent of home owners.

Other comparisons of frequent school change include the following:

• About 40 percent of migrant children change schools frequently.

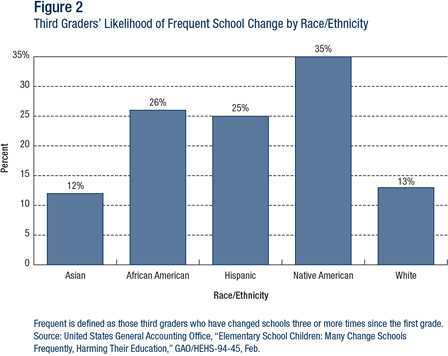

• White and Asian American third-grade students change schools at a rate of approximately 12 percent; Hispanic students, 25 percent; African American students, 26 percent; and Native Americans, 35 percent (see figure 2).

• Among children with limited English proficiency, about 34 percent change schools frequently.

|

These differences may reflect income differentials as evidenced by the 1990 Current Population Survey data, which found that race or ethnic differences in mobility largely disappeared after accounting for home ownership and renter status.

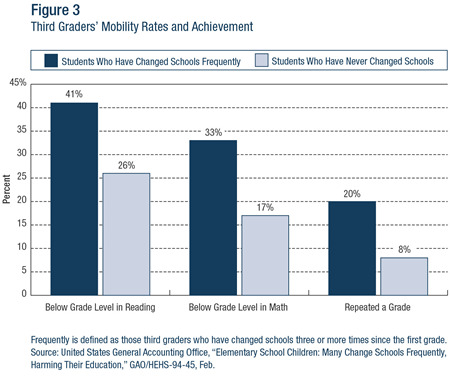

Do high mobility rates matter? In grouping children who have frequently changed schools into four income categories, the GAO study found that, within each category, children who have changed schools most frequently are more likely to be below grade level in reading and math than those who have never changed schools. Of the nation’s third graders, 41 percent of those who have changed schools frequently are low achievers (below grade level) in reading, compared with 26 percent of third graders who have never changed schools. Results are similar for math—with 33 percent of children who have changed schools frequently below grade level compared with 17 percent of those who have never changed schools (see figure 3). In addition,

• Overall, third graders who have changed schools frequently are two and a half times as likely to repeat a grade as third graders who have never changed schools (20 versus 8 percent).

• For all income groups, children who have changed schools frequently are more likely to repeat a grade than children who have never changed schools.

• Children who changed schools four or more times by the eighth grade were at least four times more likely to drop out than those who remained in the same school; this is true even after taking into account the socioeconomic status of a child’s family.

|

Why do student mobility rates have such a strong effect on performance? Some theorize that the lack of coherency in curricula across the United States, within states, and often between schools in the same district is a major cause. After much research, Herbert Walberg concluded, “common learning goals, curriculum, and assessment within states (or within an entire nation) . . . also alleviate the grave learning disabilities faced by children, especially poorly achieving children who move from one district to another with different curricula, assessment, and goals.”

School choice could contribute to a partial solution by breaking the link between a child’s home address and school address, thus allowing students to remain at the same school despite moving. Hirsch and other experts argue, however, that what is needed is a strong and coordinated core curriculum to provide a solid, consistent foundation in the basics. Although a national curriculum would be dangerous because of its potential for jeopardizing local control, a well-defined basic core curriculum would be beneficial. Without a coordinated sequence, too much time is spent repeating certain fundamentals of a student’s education and completely ignoring others. Although choice, local control, and autonomy are important, clear standards and a coordinated sequence could provide a foundation for closing the achievement gap.