Economics 101 teaches that only efficient businesses survive and prosper in competitive markets. Customer living standards rise, prices fall. Monopolies, in contrast, earn extraordinary profits, provide poor customer service, charge inflated prices, and lower living standards. Economists of all stripes favor competition and warn against monopoly.

These facts set the stage for understanding the recent stories about Walmart’s legal problems in Mexico. News outlets such as the New York Times told readers of a “vast Mexico bribery case hushed up by Walmart after top-level struggle,” suggesting that the giant retailer had violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Walmart de Mexico apparently had hired two outside lawyers seven years ago to “facilitate” store permits. “Legal and bureaucratic obstacles melted away after payments were made to minor officials who could thwart Walmart’s growth,” reported the Times. Walmart executives failed to take appropriate action after an internal investigation, the report said.

No believer in free enterprise should excuse or make light of legal violations by Walmart or any other company, and Walmart should move forcefully to put this business behind it. But anti-Walmart fervor led the Times to ignore some inconvenient facts. It failed to pursue the possibility—if not probability—that local officials could not pass up a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to extort money from the big corporation. Nor did it give any credit for the chain’s success in Mexico to something as simple as “everyday low prices,” not when a more nefarious angle was available.

The Times’ biggest sin was in neglecting the big picture—one in which Walmart, far from distorting Mexico’s economy, has been chipping away at the monopolies that have long exploited Mexican consumers.

THE SWEET LIFE OF THE MONOPOLIST

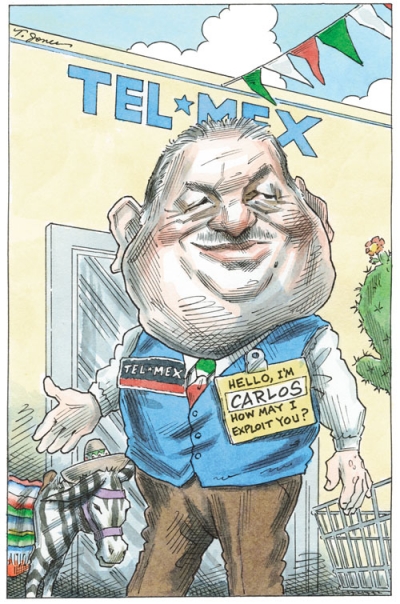

A few blocks away from Times headquarters in New York, Carlos Slim, the Times’ second-largest shareholder behind the Sulzbergers, oversees his sprawling telecommunications empires from atop Rockefeller Center. Slim is a welcome guest at the most exclusive Manhattan cocktail parties, fetes where Walmart’s hillbilly executives from Bentonville, Arkansas, would simply not fit in.

Slim, the world’s richest man and owner of Telmex, Mexico’s telephone monopoly, has retarded Mexico’s economic development and reduced its standard of living even as Walmart de Mexico raised those standards, particularly among the poor. Quotations from Mexican websites hint at the many ways consumers run afoul of non-competitive markets in telecommunications and elsewhere:

“(Mexico’s) monopolized telephone system charges outrageous prices, causing people to avoid using the phone.” (Mexican retirement website)

“With the money I save at Walmart, I take my family to the movies.” (Interview with a Mexican plumber)

“Until recently, relatively few people had a private home telephone line, due to the high cost of installation.” (Vallarta Online)

“Spam goes for 26.00 at Walmart, 28.50 at Soriana, and 37.50 at SuperLake. U.S. brand peanut butter is consistently cheaper at Walmart and Soriana than at SuperLake.” (Guadalajara Online)

Slim was the high bidder for Mexico’s dilapidated national telephone company when it was privatized in 1990. He was wealthy at the time, but not in the top one hundred. It was Telmex that made him the world’s richest man, quite a feat for someone from a desperately poor country.

A shopper enters a Walmart store in Mexico City. Walmart de Mexico is the largest private employer in the country, with over two hundred thousand employees in more than two thousand retail outlets.

Slim’s story is business as usual in a crony-capitalist country. Using his close ties to the dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), Slim arranged to pay for Telmex out of company profits. He gained a seven-year antitrust exemption that freed him to operate Telmex as a monopoly—a deal in his interests but contrary to the interests of the people. Slim’s monopoly gave Mexico one of the worst connection rates in the world, and its customers continue to pay among the highest rates for telephone service. Telmex’s profit of 40-plus percent caused Slim’s personal wealth to soar. Not until last year did Mexico’s antitrust watchdog begin breathing down his neck.

A 2012 report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) into telecom reform reveals the damage Slim’s Telmex has wreaked on the Mexican economy:

Slim’s $13.4 billion overcharge cost the average Mexican household some $600 per year, or over 6 percent of household income. Slim, it seems, became the world’s richest man at the expense of an entire country.

THE COST OF CRONY CAPITALISM

Walmart de Mexico is quite a different kettle of fish.

We do not have special studies of the “Walmart effect” on Mexico’s retail market, but it must have been as great as or greater than in the United States. Walmart directly saved American households more than $200 a year in lower prices—a gross underestimate in that it leaves out Walmart’s contribution to increasing competition. Walmart also raised productivity throughout the economy. McKinsey, in its exhaustive study of U.S. productivity, concludes that:

Walmart de Mexico is the largest private employer in Mexico, with over two hundred thousand employees in its more than two thousand retail outlets. It earns a competitive profit and has made Mexico richer. Walmart’s rivals—Comercial Mexicana, Soriana, and Gigante—have overhauled their purchasing and pricing strategies, revamped their stores, introduced new products, and spent heavily on computer systems and distribution centers. They are giving Walmart a run for its money.

As an observer of Russia in the 1990s, I was an eyewitness to the transition from street-mafia corruption to crony capitalism. Up until the mid-1990s, crew-cut young thugs dressed in jogging outfits shook down store-owners. Without their “protection,” the shops could not stay in business. In the second half of the 1990s, I saw health, tax, and fire inspectors displacing the street thugs, but now the shakedown was by state officials. Under Vladimir Putin, the mafia game moved to the highest levels. Putin’s KGB state now hands out monopolies to favored billionaire oligarchs and state officials.

Walmart de Mexico was a captive of the state inspector, without whose permission it would not be possible to do business. The level of competition and normal profit rates in the Mexican market tell us that Walmart did not freeze out competitors. All it wanted was a chance to compete.

We will never know what deals Carlos Slim made to gain his Telmex monopoly, but we know this was crony capitalism in its most destructive form. The damage to the Mexican standard of living has been heavy. Perhaps news outlets like the Times could ferret out the kind of corruption and inefficiencies that plague state-sanctioned monopolies—and government-private partnerships—rather than taking cheap swipes at Walmart.