To verify the adage “What a difference a year makes,” look no further than the recently concluded bill-signing season in Sacramento, a one-month stretch from mid-September to mid-October during which California’s governor approves or vetoes pending legislation (matters on which the governor doesn’t act automatically become law).

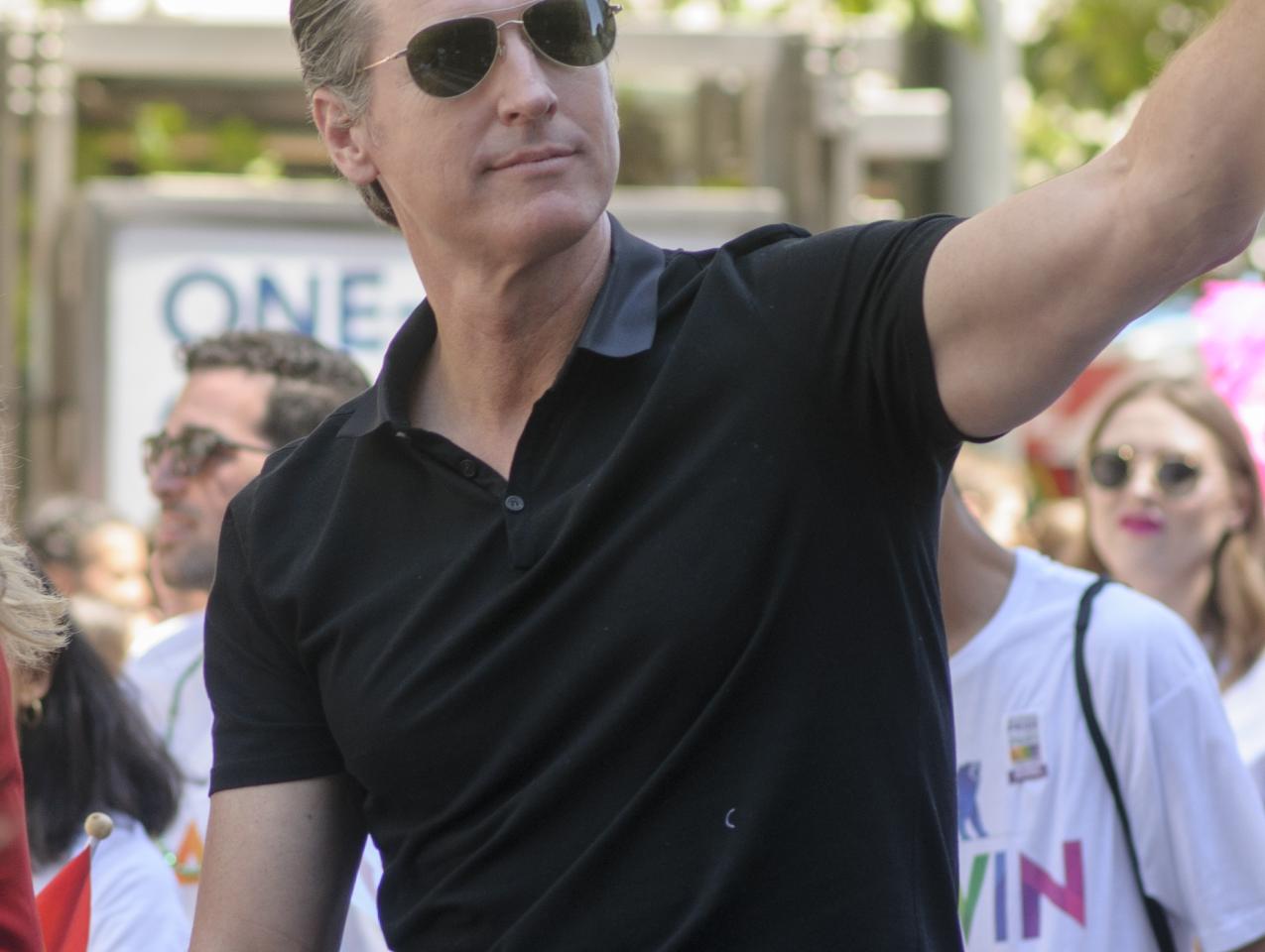

What we learned: Gavin Newsom, in his first year as California’s 40th governor, has a flair for the dramatic—specifically, head-turning, headline-grabbing news nuggets.

A new law paving the way for California collegiate athletes to cash in on their images made a national splash, as did a separate measure making California the nation’s first state to push back schools’ starting times as of the 2022–23 academic year (in an interesting political twist, Newsom’s decision riled the all-powerful California Teachers Union, a rare choice for a California Democrat).

We also learned that Newsom lives by the credo “WWJD”—the “J” in this case being not Jesus but Jerry . . . as in Jerry Brown, his gubernatorial predecessor. Only, rather than following Jerry’s lead, Newsom seemingly delights in doing the opposite.

In 2017, Brown vetoed the aforementioned school-start bill (“These are the types of decisions best handled in the community,” he wrote in his veto message). Brown also vetoed a proposed ban on private prisons; on that one, Newsom’s gone the other way.

Last year, Brown nixed a bill requiring California’s public universities to stock abortion medication. Newsom pulled a one-eighty: come 2023, California’s UC and CSU campuses will be required to offer students medical abortions—specifically, a nonsurgical termination that entails taking two prescription pills during the first 10 weeks of a pregnancy so as to induce a miscarriage.

Something else Newsom demonstrated: a fondness for matters seemingly picayune yet dripping in political correctness.

With a stroke of the governor’s pen, California bid farewell to tiny shampoo bottles, barred most circus animals from performing in the Golden State (presumably, that doesn’t apply to state lawmakers), allowed motorists to take home and dine on roadkill (the so-called “kill it and grill it” bill) and put a kibosh on the sale and production of animal fur products (one wonders how this affects First Partner Jennifer Siebel Newsom’s fashion choices).

In sum, Newsom sported roughly the same veto percentage in his first year as did Brown in his last. However, the first year of the Newsom regime, to paraphrase the old USC football run-play, was “student body left”—Newsom signing 15 new gun-restriction laws, a new law allowing marijuana businesses to claim state tax deductions (one of eight cannabis-related measures he OK’d), plus a bill allowing undocumented residents to serve on California state government boards.

In politics, there are exceptions to rules. That also applies to Gavin Newsom’s bill-signing choices.

On at least occasion, the new governor didn’t deviate from his predecessors—Newsom becoming the third consecutive California governor to veto a bill that sought to change the process for qualifying initiatives for the state ballot.

AB 1451, as put before the governor, would have made it a misdemeanor to pay signature-gatherers based on the number of signatures they collect on an initiative, referendum, or recall petition, and required at least 10% of signatures on a state initiative petition to be collected by unpaid circulators.

Newsom’s veto rationale: “While I appreciate the intent of this legislation to incentivize grassroots support for the initiative process, I believe this measure could make the qualification of many initiatives cost-prohibitive, thereby having the opposite effect.”

Newsom added, “I am a strong supporter of California’s system of direct democracy and am reluctant to sign any bill that erects barriers to citizen participation in the electoral process.”

(Lest you think California’s governor is a democratic altruist, he also signed a law enabling Golden State voters to register on Election Day—the previous deadline was 15 days before an election—as well as expanding so-called conditional voter registration that allows new voters to cast a ballot that’s counted after eligibility is determined during the month-long vote-counting period after an election. Both should help Democrats pad their advantage in statewide elections).

Now, the reason why the AB 1451 veto caught my eye.

On the one hand, it’s no surprise that Newsom would defend the sanctity of the initiative process. Two ballot measures that he championed in the November 2016 election—Proposition 63 (background checks for ammunition purchases and a ban on large-capacity ammunition magazines) and Proposition 64 (legalizing recreational marijuana)—provided a soft-launch for Newsom’s 2018 gubernatorial run.

On the other hand, Newsom’s veto is curious in that he passed on an opportunity to put another nail in the California Republicans’ coffin. To borrow a line from a W. C. Fields film: never give a sucker an even break.

At present, the California GOP is on the short end of 60-20 and 29-11 “superminorities” in the State Assembly and State Senate, respectively. Meanwhile, no California Republican holds a statewide constitutional office—nor came close to winning one in 2018.

Unable to block legislation and lacking bully pulpits in Sacramento, how can Republicans push back against “student body left”?

The initiative process, of course.

California saw a preview of what the future may hold last fall, when

conservative activists attempted to pass Proposition 6, a repeal of increases on the state gasoline tax and motor vehicle fees (those increases, which took effect in November 2017, imposed taxes of 12 cents per gallon on gas and 20 cents per gallon on diesel fuel. It also levied a new $25 to $175 license fee on vehicles.

While Prop 6 failed—with Brown and his allies arguing that voting for the measure would halt repairs to California’s ailing infrastructure—watch for repeats of this in future November elections: the right trying, by initiatives and referenda, to undo what the left powers through in Sacramento.

And also keep an eye on how Democratic lawmakers try to manipulate the initiative. One such example: California state attorney general Xavier Becerra giving a friendly title and summary to a revised ballot measure that would alter Proposition 13. (The old initiative summary that Becerra agreed to last year said the measure “requires certain commercial and industrial real property to be taxed based on fair-market value. Dedicates portion of any increased revenue to education and local service.” The new title reads that it “increases funding for public schools, community colleges, and local government services by changing tax assessment of commercial and industrial property.”)

The good news for Newsom: characterizing initiatives more to the left’s liking makes for an easier sale to his left-of-center base.

And if the governor enjoyed engaging in initiatives politics in 2016, before he landed his present job, he may get a lot more chances to do the same in the elections ahead.