- Education

- K-12

There used to be a lot of school kids crowding the Surratt House Museum in Clinton, Maryland, a few miles south of Washington. Their teachers would haul them in by the busload—more than a thousand a year. The museum is housed in the homestead of one of the conspirators who was hanged for the murder of Abraham Lincoln. It’s small, but it offers an unexpectedly comprehensive review of the Civil War, with a special emphasis on the assassination, and for years grade-school teachers in southern Maryland have used a field trip there as a convenient way to keep their students awake long enough to introduce them to an important episode in their nation’s history.

In the past couple of years, though, attendance has dried up—cut by more than half, according to Laurie Verge, the museum’s director. Laurie is a former history teacher herself. From talks with old colleagues, she’s pretty sure how to account for the undesired quiet that has fallen over her museum most weekdays: “The schools just don’t have as much room for history or social studies in their curriculums any more,” she says. “Ever since No Child Left Behind.”

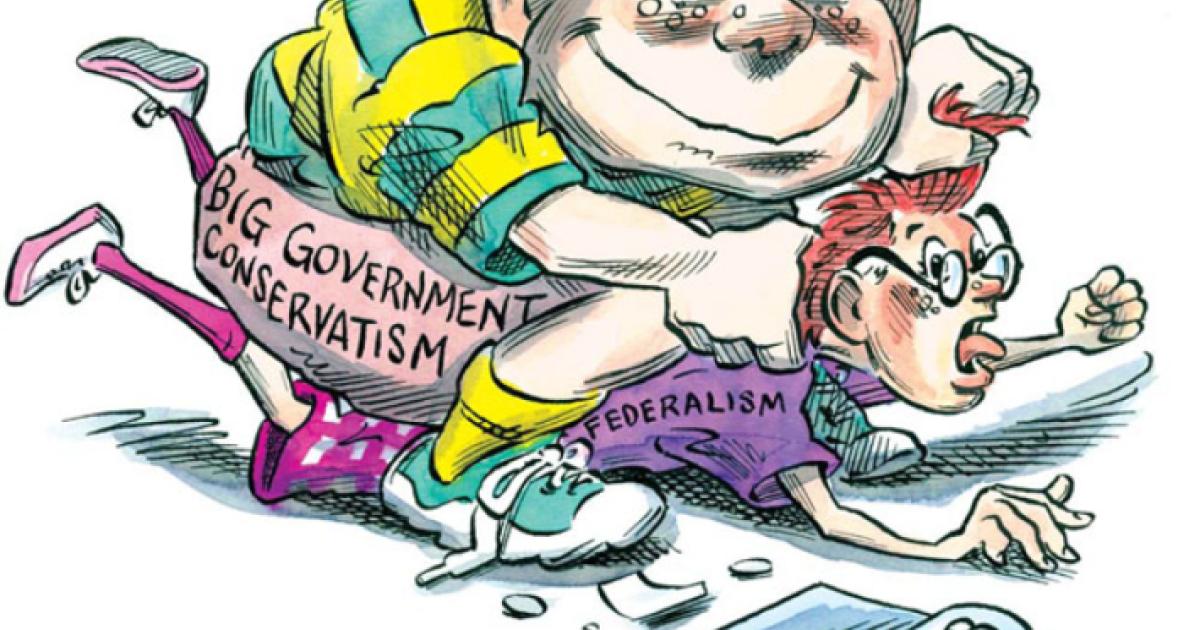

That would be the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, or NCLB as it has come to be known, the totem of national education reform and bipartisan bonhomie that for six years has stood as the signal domestic achievement of the Bush administration—and the exemplar of the Big Government Conservatism with which George W. Bush’s reformers hoped to remake the way Republicans govern. Among many other things, the bill authorized the federal Department of Education to subject every student in every public school in the country to an elaborate regime of testing in reading and math. How well the students do on those tests determines how much money their schools and school districts receive from the federal government, and determines also, in remarkable detail, how the federal government will allow that money to be spent.

Reformers are busy people, tireless people whose displeasure with the world as it is inspires them to improve the lives of their fellow human beings no matter what, and they get cranky when you bring up the law of unintended consequences. They dislike the implication that the benefits they confer on one field might lead to shrinking benefits in another. Yet the decline in attendance at Laurie Verge’s wonderful little museum is, indeed, an unintended consequence of NCLB—just one of many and a small one at that. Though no one thought of it in the long, sweaty hours while the bill was being written, or mentioned it in the self-congratulatory giddiness surrounding its final passage, NCLB’s exclusive emphasis on reading and math has led a high percentage of schools (around 40 percent, according to one recent survey) to cut back on the teaching of history, civics, and government to the country’s schoolchildren.

The irony is hard to avoid: Republicans, who used to lament the rising tide of “historical illiteracy,” have now reformed the nation’s schools in such a way that can only swell the tide. But there are lots of ironies in Big Government Conservatism. Michael Tanner, of the libertarian Cato Institute, devotes one chapter to NCLB in his new manifesto against BGC. In Leviathan on the Right: How Big-Government Conservativism Brought down the Republican Revolution, his critique of both the education reform and the philosophy it grew from is unrelenting, absolute, and refreshingly dyspeptic. With the authors of the other books I will cite here, liberal and conservative alike, he shares the near-universal diagnosis of the country’s education troubles:

No one can deny the need to reform our education system. Our society is becoming increasingly divided between those with the skills and education needed to function in the increasingly competitive global economy and those without such skills and education. At the same time that education is becoming increasingly crucial, government schools are doing an increasingly poor job of educating children.

(“Government schools,” by the way, is libertarian for “public schools.”) Evidence for the failure of the schools, as Tanner says, is long-standing and everywhere. It’s found in a generation’s worth of falling test scores and in the poor performance of U.S. schoolchildren in international rankings (21st in math, 16th in science). Among federal officeholders, including some Republicans, feeble education has been a public concern for a long time. The decline in schools, from the conservative point of view, has had many causes: poorly trained teachers, undemanding curriculums suffused with political correctness and multiculturalism, the abandonment of drill and memorization and other traditional tools of learning, and a general refusal on the part of a new generation of administrators to impose, and live up to, high standards of achievement. And one way to reverse these trends, it was thought, was to hold schools accountable for the education of their students: test the kids, publish the scores, and let parents, armed with the results, decide whether the teachers and administrators were doing the job they were hired to do.

It’s certainly a sound idea—which is not, of course, the same thing as saying it—s an idea that should be imposed nationwide by the employees of the Department of Education. The distinction is usually lost on the practitioners of BGC. Their premise, as Tanner puts it, is this: “If something is a good idea, it needs to be a federal program.” In the past, of course, this eagerness to nationalize good intentions has been more commonly associated with Democrats than Republicans. But that was before the onset of BGC.

The seeds were sown in the 1990s, when the most powerful and successful officeholders in the Republican Party were governors. With the executive branch in Washington in the hands of Democrats, Republicans were ardent believers in the principles of federalism and subsidiarity. Subsidiarity— the idea, if not the word—had long been considered essential to the American scheme of dispersed power: there are spheres of action appropriate to state governments, and to local governments, that are not appropriate to the federal government. Some things are controlled by only one level of government, in other words, so that no one level of government controls everything. Subsidiarity acts as a stay. It requires, on the part of the governing class, a restraint and humility unique to self-government—a willingness not to exert power over others, no matter how tempting the thought might be or how admirable the cause.

“As I would not be a slave,” said the founder of modern American conservatism, Abraham Lincoln, “so I would not be a master.”

But in the 1990s, federalism and subsidiarity had political benefits, too, as the governors discovered. States, Republicans said (borrowing a phrase from the socialist Louis Brandeis), were “the laboratories of democracy,” hothouses of the hinterland. It was there that new ideas in welfare policy, education, taxation, and environmental regulation could be put into practice and their results tested and measured, while keeping the (Democratic) busybodies of Washington at bay. Even better, or so it seemed, the passion for state and local activism allowed Republicans to overcome their reputation for being antagonistic to government. It wasn’t just Democrats who embraced, as the phrase went, “proactive solutions to today’s problems.”

One of those can-do Republican governors of the 1990s was George W. Bush. When he gained the White House, no one should have been surprised that he transferred his taste for “conservative activism” to the biggest laboratory of them all, the federal government.

“I care about results,” he said often during the 2000 campaign. “I’m passionate about getting things done.” His passion for federalism, however, was less ardent, and it terminated with his governorship. For Big Government Conservatives, as Tanner shows, subsidiarity is an indulgence that people serious about governing can’t afford.

“At a fundamental level,” he writes, “Big-government conservatives are much more concerned with ends than means. Something as process-oriented as federalism can’t be allowed to get in the way of doing things that big-government conservatives believe need to be done.” This was true even in the treatment of public schools, where the tradition of local control is as old as the institutions themselves. In putting together NCLB, all the BGCs of the Bush administration had to ask themselves was: will this work? Given the national calamity of failing schools, self-restraint seemed almost irresponsible.

In this Bismarckian approach to “getting things done,” modern liberalism and BGC are essentially indistinguishable. “Big-government conservatives,” writes Tanner, with his usual acerbity, “share a common arrogance with contemporary liberalism.” Nowhere is the impertinence better displayed than in NCLB—so much so that Tanner, a rightward-leaning libertarian, wonders whether the act can even be considered “conservative” in any identifiable sense at all.

Scott Franklin Abernathy, a political scientist at the University of Minnesota, wonders the same thing and arrives at the same conclusion, from the opposite direction. On the evidence of his new book, No Child Left Behind and the Public Schools, Abernathy is no Republican. But he is a great booster of NCLB, which he sees more clearly than many Republicans do. The overriding goal of NCLB, as he notes, is to close the “achievement gap” between students who perform well in school and those who perform poorly. (Confusingly—in a mistake common among education reformers—Abernathy calls the former “advantaged” students and the latter “disadvantaged” students, though of course many students from wealthy families do horribly in school while many poor students excel.)

“If properly implemented and sufficiently funded,” writes Abernathy, “NCLB holds the promise of being one of the great liberal reforms in the history of U.S. education.” Earlier reforms, such as mandated busing or the Americans with Disabilities Act, were “about equality of opportunity; NCLB aims to provide equality of outcomes. This is a very radical and ambitious goal.”

In their indispensable primer on NCLB, No Child Left Behind, Frederick Hess and Hoover research fellow Michael Petrilli make the same point, quoting the education adviser to John Kerry: “At its heart, this is the sort of law liberals once dreamed about. . . . The law requires a form of affirmative action: States must show that minority and poor students are achieving proficiency like everyone else, or else provide remedies targeted to the schools those students attend.”

The goal of forcing equality in performance would have been beyond the wildest dreams of the most starry-eyed reformers back in 1965, when the federal bureaucracy made its first great lunge at local schools. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act was a cornerstone of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and the forerunner of NCLB. The motive behind the 1965 act was, as reformers’ motives always are, beyond criticism: a desire to improve schools in poor neighborhoods.

“Our society will not rest until every young mind is set free to scan the farther reaches of thought and imagination,” said LBJ, and American schools have been declining ever since. The same extravagance and grandiosity would reappear in Bush’s education speeches 40 years later. The difference is that Bush tried to write his into law.

To close the achievement gap, NCLB requires that every teacher in America be “highly qualified” and that every student be “proficient” in reading and math by the 2013–14 school year—a 100 percent success rate that no government program has ever reached. Johnson’s bill mostly left good schools alone, showering poor schools with money in hopes they might become good schools. NCLB ropes all schools together, entangling successful schools in the same bureaucratic regime designed for schools where most students aren’t succeeding.

The statistics generated by the law are impenetrable to all but the bureaucrats themselves. NCLB, for example, makes a fetish of racial classification; it is, indeed, the most explicitly racialist piece of legislation since the fall of Jim Crow. (The principle of color blindness is another nicety that Big Government Conservatives have no patience for.) Students in every school are zippered-up into eight different categories, five having to do with race and ethnicity, three with income and the ability to speak English. If students in any one of these categories fail to perform to the Department of Education’s demands, the entire school faces sanctions. Over time the sanctions grow increasingly severe. After a few years, the Education Department nationalizes the school, dictating budgets, personnel policies, and hiring decisions.

By Abernathy’s reckoning, an individual school or district can earn failing marks in 36 possible ways and thus find itself an object of special attention from Washington. What happens to those schools’ well-performing students, who will see resources diverted or dry up altogether, is apparently a matter of indifference—another unintended consequence.

The problem of leveling doesn’t trouble Abernathy too much. He dwells, instead, on the more conventional objections made by reformers who think NCLB does’’t go far enough in nationalizing local schools. In a nod to federalism that seems quaint in retrospect, NCLB allowed the states to define “proficiency” and “highly qualified.” Abernathy worries that the lack of a single standard makes cross-state comparisons, and even school-to-school comparisons, difficult and sometimes impossible. It also opens statistical loopholes that allow individual schools, school districts, and entire states to create the impression that they’re meeting NCLB goals when they’re not.

To satisfy these objections, federal policymakers would have to make NCLB even more intrusive than it is. And sure enough, some BGCs have begun calling for the Education Department to impose national standardized tests fitted to a national curriculum in reading and math. The step is already implicit in the logic of NCLB. In fact, this final sweeping away of the vestiges of local control would probably be inevitable, except that some supporters of NCLB have come to dislike the very idea of standardized tests—the primary means of establishing the “accountability” that Big Government Conservatives say lies at the heart of the law.

Standardized tests are one size fits all, say the critics: clumsy and crude tests that can never adequately measure student achievement. The worry, says Abernathy, is that teachers, hamstrung by NCLB, are smothering their marvelous creativity and resigning themselves to “teaching to the test.” This is another way of saying that standardized tests, at least in theory, require teachers in the classroom to forgo therapeutic exercises in self-expression and transmit concrete information that a child can absorb, entertain, manipulate, and repeat. In an earlier age, the word for this process was “teaching.” Now it is a threat to our educators’ self-image—indeed, their way of life.

Abernathy’s antitesting bias is widely shared, even, as he shows, among supporters of NCLB. As a philosophical proposition, the bias leads sooner or later to a kind of cul-de-sac of postmodern relativism: who’s to say, really, what a good education is? “So many factors,” Abernathy writes, “contribute to and confound what ultimately happens at the interface between a student’s mind and the schoo’’s products that policymakers should think very carefully about how to measure ‘educational quality.‘“

Note the ironic quotation marks around those last two words, as though the idea of educational quality was some sort of fuddy-duddyism, like “motorcar,” that no up-to-date person would use. “Can we ever really know if a child’s education is good?” he asks.

(Leave aside the issue of whether education can really be reformed by people who invent phrases like “the interface between a student’s mind and the school’s product.”) Abernathy’s question represents a potentially fatal objection to NCLB, coming as it does from a vigorous supporter of the law. It strikes directly at the case that BGCs have made for their education reform, which, after all, aims during the next seven years to ensure that the education that every student receives is good—provably and objectively good, without ironic quote marks.

But Abernathy does give us a sense of how the vast new powers that NCLB has handed to functionaries in Washington will be used, and will not be used, when the Republican functionaries are replaced by Democratic functionaries—when supervision of the Department of Education is given over, as it will be inevitably, to those who dislike the BGC emphasis on standardized tests and “accountability.”

Meet, for instance, Howard Good, an education activist, former president of his local school board, journalism professor with the State University of New York, and a frequent contributor to American School Board Journal, Education Week, and Teacher Magazine. I have no idea whether Good would ever make the trek to Washington to serve as a political appointee in President Obama’s Department of Education, but people who think just like him will; his Mis-Education in Schools: Beyond the Slogans and Double-Talk (his fifth book on education) exquisitely displays the turn of mind that we can soon expect to see in the upper reaches of the federal educational establishment.

Like Abernathy, Good defines education loosely. Education means pretty much whatever anybody wants it to mean—and who are you, or anybody else, to disagree? He writes:

My mom was my first teacher. The stuff she taught me—how to tie my shoes, cook an omelet, read for pleasure, speak my mind—has proved more useful and durable than most of what I learned in school. . . . Schools today wouldn’t dare adopt this as their educational agenda, even if it meant happier kids and a better world. Why? Student tests might suffer.

His reference to tests is meant to be witheringly ironic. About NCLB itself, Good is ambivalent—like the BGCs, he doesn’t object in principle to federal interference with local schools, as long as people like him are doing the interfering, and the more money spent, the better—but he’s outraged at all this talk of tests. Testing can only make the inequality worse, which, he says, is an offense against the egalitarian impulse that should animate the public schools. He approvingly quotes a professional educator: “Let’s put all our children in the same boat, then work together to raise the level of the river.”

“At the very least,” he writes, “let’s abandon the notion that children who learn on a different schedule are ‘Special’ or —Regular’—edspeak for ‘inferior.’ They aren’t; no child who’s loved by someone else ever is.”

This last sentence—so precious, so heartwarming, so thoroughly beside the point—gives a sense of Good’s command of logic. As you read his thoughts about schools’ teaching “what truly counts in life,” in contrast to those Neanderthals who insist on teaching facts and conveying information, you can easily imagine his manuscript as it arrived at his publisher’s office, with the little doodles of unicorns and rainbows up and down the margins in purple ink. What’s interesting is that so many of his objections to modern schooling are made by right-wingers, too. Good is correct that social studies curriculums are often timid and wandering. Many schools are overformalized and overregulated, requiring (for example) student athletes to sign “contracts” not to smoke or use drugs rather than just insisting they not smoke or use drugs. Administrators are often petty and overweening. The emphasis on elite sports teams is, as he says, an expensive distraction from a school’s primary purpose.

His fixes, however, are another matter. He thinks schools should more or less abandon efforts to discourage drug use. He worries that the dissatisfaction with mushy social studies might lead to a return of “teachers who emphasize rote memorization of facts and textbooks that contain dry outlines of procedures (how a bill becomes law and so forth).” Instead, he longs for teachers who teach “tolerance for ambiguity and an aversion to either/or solutions.” Perhaps, he says, schoolkids could learn about democracy by voting on which books to read during storytime as a way of “modeling” the responsibilities of citizenship. It sure beats learning how some boring old bill becomes some stupid law.

Every school district has a kibitzing parent like Howard Good; some school districts are overrun with Howard Goods. Such culture war disputes will be no more tolerable, or resolvable, when they are nationalized, as NCLB aims to do. Howard Good and his allies will be unstoppable when they at last regain power in Washington. Mandatory omelet making, maybe?

How to disentangle the Gordian knot tied by NCLB and its reformers? This, lucky for us, is the question that Myron Lieberman addresses in The Educational Morass: Overcoming the Stalemate in American Education. A former public school teacher and for many years an official with the American Federation of Teachers, Lieberman has written the bravest, most bracing book about education in years. He strips NCLB and the accumulated daydreams of education reform down to their bare premises and, with discomfiting logic, tips them over, one by one. His book will almost certainly be ignored.

Lieberman reminds us of truths that have been repeatedly demonstrated, statistically and otherwise, since 1965: there is no correlation between how much the government spends on schools and how much students learn; meanwhile, of course, the Bush administration boasts that it has increased federal education spending by more than 40 percent, and Democratic critics complain that NCLB hasn’t been “fully funded.”

As for the achievement gap, the principal target of NCLB: no research has ever established that the quality of individual schools is a cause of the gap in test scores among groups of students—especially compared with the other facts in a student’s life, such as the safety of her neighborhood, the income of his family, the presence of books in his home, the amount of television she’s allowed to watch, or whether he’s being raised by a mother and a father: facts, every one of them, beyond the manipulation of any education reformer.

Lieberman asks reformers in Washington, sometimes politely, to consider the practical consequences of the reforms they hope to impose on schools. How, precisely, would each reform work? Every good Big Government Conservative, of course, wants schools to hire better teachers, for example—and bravely, unflinchingly, the BGC will acknowledge that this will require paying teachers more. At the same time, also of course, every BGC wants smaller class sizes, too.

Well, says Lieberman, let’s think this through. If we make classes smaller, we’ll have to hire more teachers. If we have to hire more teachers, we’ll have to expand the pool from which new teachers are hired. If we expand the pool, we’re likely to see a drop in the quality of applicants and hires, which will defeat our goal of hiring better teachers. And if we do enlarge the teacher workforce, we’ll make any hoped-for increase in teacher pay much less affordable and, hence, less likely—especially when the pay is matched with an increase in benefits, which routinely account for 20 percent of a teacher’s compensation. And better teachers are unlikely to materialize without an increase in pay.

Lieberman dares to run the numbers, and they are daunting. The Teaching Commission, yet another blue-ribbon panel led by business executives dedicated to improving public education, has proposed a salary increase for teachers nationwide of 10 percent—as much as 30 percent for teachers who are identified (in some unnamed fashion) as the most effective in the classroom. The cost, Lieberman reckons, would be $33.6 billion annually. The pay raise would have several other effects. It would increase pressure to enlarge class size—even though the reformers who demand higher teacher pay also demand smaller classes. Pressure would intensify for a 10 to 30 percent raise in the salaries of support personnel as well, doubling or tripling the expense of an increase in teacher pay.

And because the base pensions of most teachers are computed on the salaries of the final three years of their careers, a large but incremental boost in pay would lead to fewer retirements, thus slowing the infusion of new talent that the reformers say is so desperately needed. And so on and so on and so on.

To their credit, some BGCs understand some of the practical difficulties in an across-the-board increase in teacher pay. They advocate “merit pay” instead—rewarding teachers for how well they teach. Merit pay especially flutters the hearts of BGCs who don’t consider how their ideas might work when they collide with the real world. Leave aside the fact that, in many countries whose students outperform the United States, merit pay for teachers is not only discouraged but outlawed. Lieberman asks the practical questions about how merit pay would work here.

Who, for example, will choose which teachers receive merit pay increases? “The majority of principals,” he says, in a voice heavy with experience, “will not want the assignment.” Teachers who are passed over will challenge the assessments, to put it mildly, subjecting whoever made the decisions to a degree of scrutiny that few professionals, in whatever field, would welcome. Fair and accurate assessments of how well a teacher does his job would require considerable hours spent watching him in action, in the classroom—a distraction for principals and administrators, who oversee dozens and sometimes hundreds of teachers, that would be prohibitively expensive, both in time and in money.

None of this is to say that such reforms are worthless or even necessarily unworkable: Lieberman himself endorses higher pay scales and school vouchers, as well as other ideas he’s come up with himself. It’s merely an acknowledgment that the reforms are endlessly complicated and that the vast majority of their consequences are likely to be unintended. In the end, Lieberman says, how to close the “achievement gap” (merit pay, or charter schools, or smaller class size, or more testing, or any other reform encouraged by NCLB) remains an “unresolved quandary.”

This may be the most radical notion in all the current crop of education books. Imagine an education reformer admitting ignorance! The sentiment is utterly alien to the spirit of Big Government Conservatism, where faith in the power of reformers to alter institutions however they desire, with the ultimate goal of altering human behavior in pleasing ways, is almost limitless.

Not long ago I mentioned to Laurie Verge, at the Surratt House Museum in Maryland, that Congress had discovered that some schools had cut back on teaching history, as an unintended consequence of NCLB. So two senators, Lamar Alexander and Edward Kennedy, have proposed expanding the bill to require testing in American history, too—just as it now requires testing in reading and math, which of course led some schools to cut back on teaching history. True to the spirit of big government, whether embodied by liberals or conservatives, the senators will solve the problems created by NCLB’s intrusiveness by making NCLB more intrusive. And then, I told her, maybe the busloads of kids will come pouring back to the Surratt House. Laurie sounded skeptical. “You’d think they’d just let people down here decide for themselves,” she said.