- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- History

- Military

Congress is now debating President Obama’s proposed Authorization for the Use of Limited Military Force to fight the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. Yet the president’s request for this action from Congress comes more than six months after U.S. aircraft began bombing ISIS positions in Iraq and Syria, and even if passed it is merely an authorization for the use of force, not a full-fledged state of war, which Congress has not passed since World War II. Does this mean that we have entered a dangerous new realm where, as some libertarians charge, congressional power to issue declarations of war has been superseded by runaway executive authority?

Actually, history suggests that the current pattern—of the president either using military force on his own commander-in-chief authority or winning an authorization for the use of force, but not a full-fledged state of war, from Congress—is hardly novel. Americans fought countless wars against the Indians from the early 17th century to the late 19th century without ever declaring war because Indian tribes were not recognized as sovereign entities within the Western legal understanding.

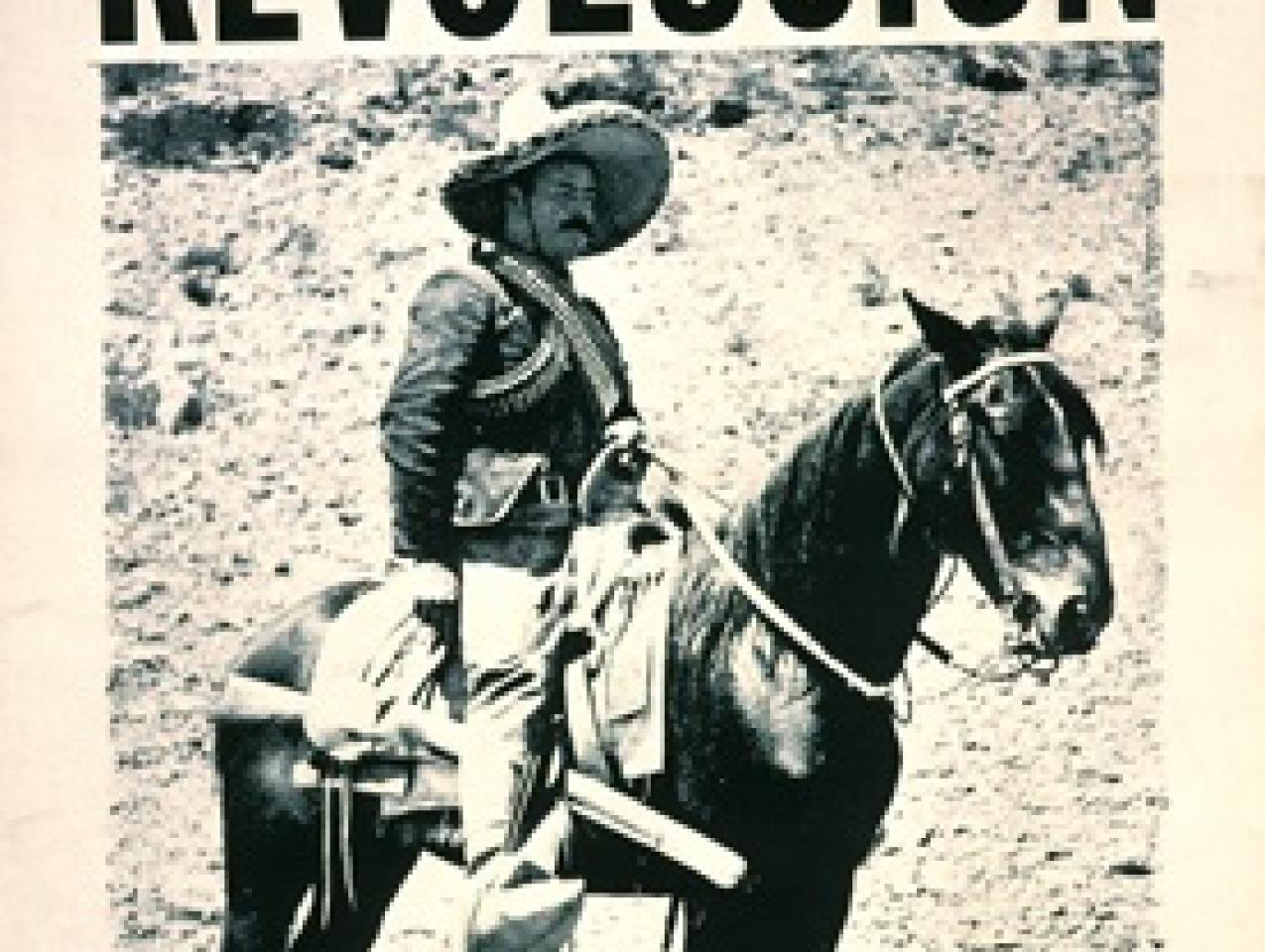

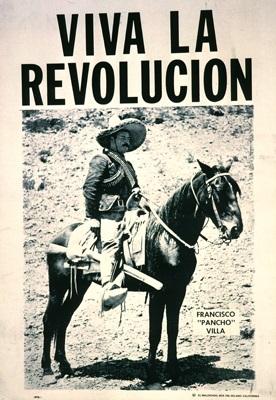

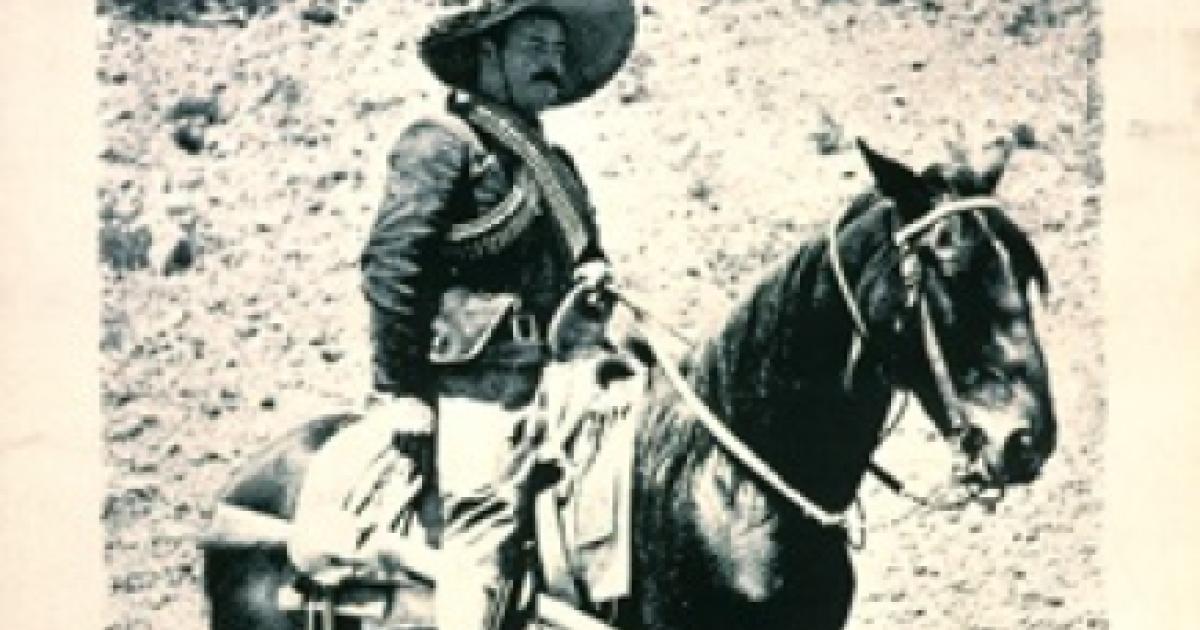

Moreover U.S. Marines landed abroad 180 times between 1800 and 1934 without any declaration of war. Occasionally there was an authorization from Congress, as was the case with the Barbary Wars (1801-1805, 1815-1816) fought against the piratical states of North Africa. More often there were simply contested landings undertaken under executive authority in such obscure locations as the Marquesas Islands (1813), Sumatra (1831), Korea (1871), and Samoa (1899). By the twentieth century some of these conflicts became quite protracted and bloody as with the U.S. occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1933, the expedition to capture Pancho Villa in 1916-1917, the dispatch of U.S. troops to Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution in 1918-1919, or to Nicaragua from 1926 to 1933.

The U.S., of course, remained a democracy throughout and Congress could have intervened anytime it wanted by utilizing its power of the purse to cut off funding for such missions—and there were in fact attempts to do just that on repeated occasions. But it was never considered necessary or proper to declare war in such instances, in no small part because, like the Indian tribes, most of the adversaries the U.S. was fighting—whether Mexican Villistas, Russian Bolsheviks or Haitian cacos—were not recognized nation-states. So too today with al-Qaeda, ISIS, and their ilk: Congress can and should weigh in but no declaration of war is needed and even without an authorization for the use of force the president has considerable authority to act in defense of American interests.