- Military

- Contemporary

- Campaigns & Elections

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

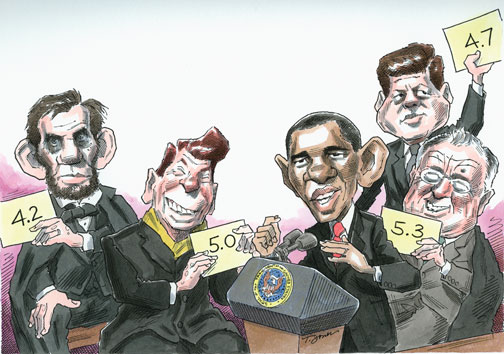

May I begin with a confession? On Inauguration Day, I went a little easy on Barack Obama’s address.

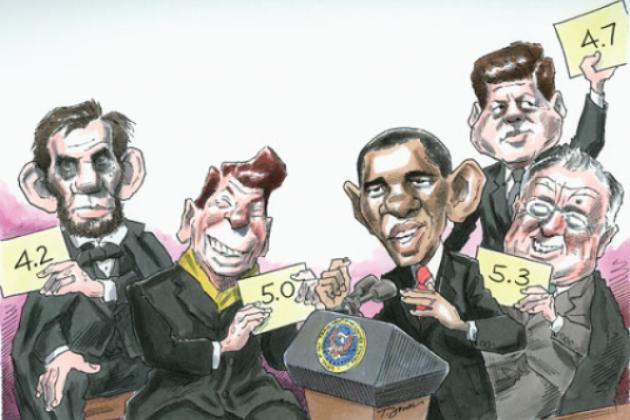

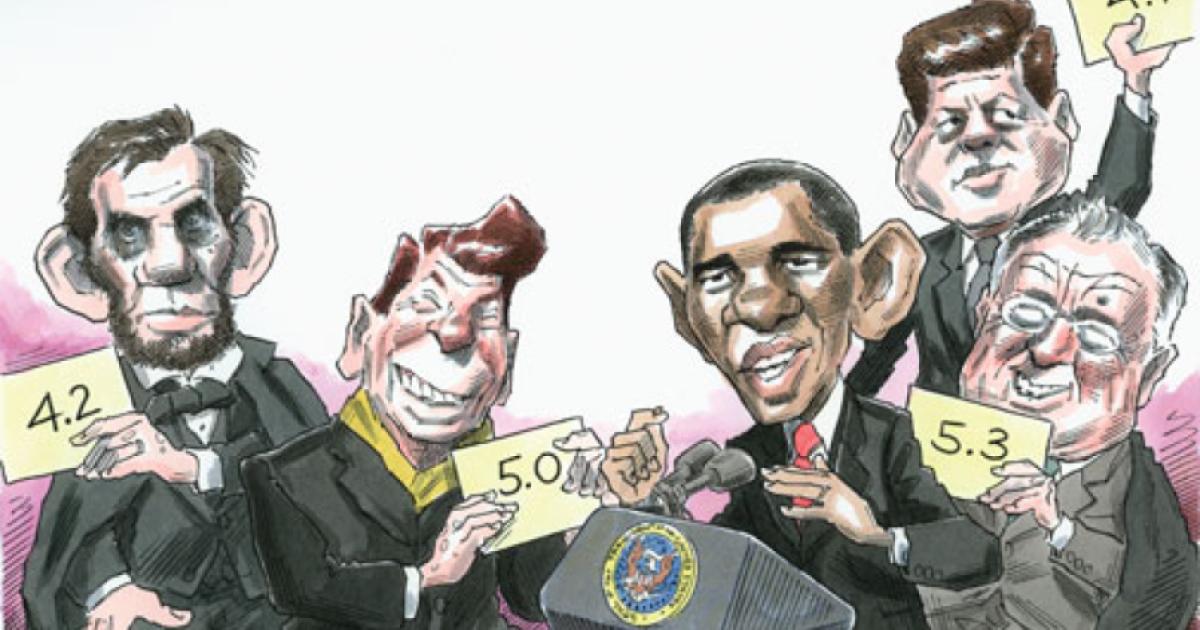

As a former White House speechwriter, I enjoy talking about public oratory. Once every four years, people pretend to be interested, and on Inauguration Day I found myself being interviewed on half a dozen radio and television programs. If asked to grade President Obama’s inaugural address, I said during one of the first interviews, I would give it at best only a B. The telephone lines lit up. “Can’t you give the man his day?” one irate caller asked. “Why do you have to be so negative?” asked another. “Everybody in America is unified right now except for you.”

For the rest of the day, I spoke a lot less about the text of the speech and a lot more about Obama’s delivery. In The Federalist Papers, I said, Alexander Hamilton insists on “energy in the executive,” and that was just what the new president displayed. Which was true. Sort of.

The callers who berated me had on their side not only the several million people who packed Washington to observe the inauguration but also the 70 percent of Americans who believed, according to the polls, that Obama was already doing a good job. But while exchanging telephone calls with friends between radio interviews, I discovered that you could have driven a Lincoln Navigator through the gap between what some journalists were saying about the inaugural address in private and what they were letting on about it in public. Nobody wants to take on the zeitgeist.

Now, long after the inaugural crowds have drained out of Washington, the emotion of the moment has dissipated.

Or so I hope. Because I’m about to say what I really thought: giving that address a B would have been too generous.

Memorability: there wasn’t any. An hour after Obama delivered the address, not a single phrase had lodged itself in the mind as particularly worthy or vivid, let alone as a coinage that would stand up over the decades. “Rising tides of prosperity”? “Still waters of peace”? Clichés.

Graciousness: there wasn’t much of that, either. George W. Bush had gone to exceptional lengths to ensure a smooth transition, even making some unpopular moves—such as asking Congress to release some $350 billion in bailout funds—to spare Obama the trouble.

Obama offered Bush no more than a single, curt sentence of thanks. Then he blamed Bush for the economic crisis, denouncing his “failure to make hard choices”—as if Bush hadn’t attempted to deal with the crisis by enacting a stimulus measure of the very kind Obama himself now pursues— and accused Bush of “protecting narrow interests.”

For that matter, the new president all but ignored the principal task of any inaugural address, that of reuniting the nation after the divisiveness of a campaign. Almost 60 million Americans cast their ballots for Senator John McCain. What did Obama have to say to his opponents? “What the cynics fail to understand is that the ground has shifted beneath them.” Some olive branch.

Philosophical coherence: Obama proclaimed a “new era of responsibility.” How does that square with a stimulus package so enormous that this year the federal budget will almost double? Executives at hundreds of corporations, officials from states and municipalities across the country—all went to Washington to lobby for bailouts.

Even San Mateo County, which has the eleventh-highest per capita income of all 3,007 counties in the nation, put in a request for aid. It’s a new era, all right. But if he wanted us to see it as an era of responsibility instead of dependency, the president had a lot more explaining to do.

Overall tone: commentators compared Obama’s address with those of two other chief executives who took office at moments of crisis: Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan. But Roosevelt and Reagan both had about them a certain lightness of touch. Their inaugural addresses conveyed buoyancy and optimism, even good cheer. Obama displayed energy, just as I said during my interviews, but it was a hard-edged energy. He has a beautiful speaking voice and a lovely, compelling poise. But he talked at his listeners.

The inauguration of our first African-American president proved historic all the same, of course—a ratification of the essential goodness of our democracy. Americans quite rightly wanted to celebrate. And we all owe our intelligent and talented new chief executive our goodwill.

But the address itself? Let me put it this way:

President Obama delivered his speech on the West Front of the Capitol, at one end of the Mall. At the other end of the Mall, forty-five years ago, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. King’s audience had participated in one of many marches that took place during the civil rights movement. We remember that march, the March on Washington, for only one reason: King’s speech.

A great speech, in other words, can confer greatness on an event.

I’m sorry to say so—really, I am—but it just doesn’t work the other way around.