- History

- Military

By declaring the Islamic State a global caliphate, Iraqi cleric Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has tapped into the universalist and utopian aspirations of Sunni extremists around the world. The Islamic State’s military successes, moreover, have offered hope to those who are desperate for a winner after defeats in such countries as Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Mali, Somalia, and Yemen. Its victories have also endowed the aspiring caliphate with material riches, including oil and American military equipment.

While self-designation as a caliphate has distinguished the Islamic State from other Islamist utopian projects, the nature of the undertaking and its challenges have several recent precedents. In the past two decades, the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaeda affiliates in Somalia, Yemen, and Mali have occupied territory and established local governments. In each case, they have been undone by a combination of draconian governance and strategic overreach. The Islamic State is at risk of sinking for the same reasons.

In each of the prior failures, the Islamist utopians alienated locals by imposing severe punishments for relatively minor violations of Islamic law, while failing to provide positive inducements such as effective governmental services. Consequently, they limited their bases of support and made enemies who subsequently helped foreign powers overthrow them. The Islamic State has learned from these experiences. In both Syria and Iraq, it has cut back on cruel punishments, shifting emphasis to educating the people on Islamic law. It has allocated funding and manpower to electricity, trash collection, and other services. Accusations of overzealousness in meting out punishment have, however, continued, and therefore the problem is likely to persist to some degree.

In most of the recent cases, foreign powers did not take action against the Islamist utopians when they first gained control over territory. Only when the movements attempted to wield power beyond their central strongholds did foreigners intervene. In the case of Afghanistan, al-Qaeda’s organization of the 9/11 attacks on Afghan territory caused the United States to drive out the Taliban. In Somalia, the Islamic Courts Union invited an Ethiopian invasion in 2006 when it tried to move beyond its initial conquests to overrun the Ethiopian-backed exile government. Four years later, after al-Shabaab had taken control over much of Somalia, al-Shabaab’s bombings of civilian targets in Kampala provoked a Ugandan intervention. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb established control over northern Mali in 2012, but then lost it the next year when its offensive into southern Mali precipitated French military intervention.

Ideology and the expectations of admirers predispose the Islamic State to pursue territorial expansion. It has already attempted to move beyond its initial Sunni Arab strongholds in Iraq to the country’s predominantly Shiite and Kurdish areas. The United States, Turkey, Iran, and other powers have helped the Shiites and Kurds to the extent required to avert total defeat, but have not yet gone on the offensive against the Islamic State. If the Islamic State is able to overrun the Shiites and Kurds, however, one or more foreign powers might well organize a large counter-offensive.

Hence, the Islamic State will be most likely to survive if it limits its ambitions in the near team. Given its modification of governance in response to past failures, chances are good that it is also mindful of repeating the error of overreach. Even a restrained approach, though, carries risks that foreign powers will enable Iraqi or Syrian security forces to vanquish the Islamic State.

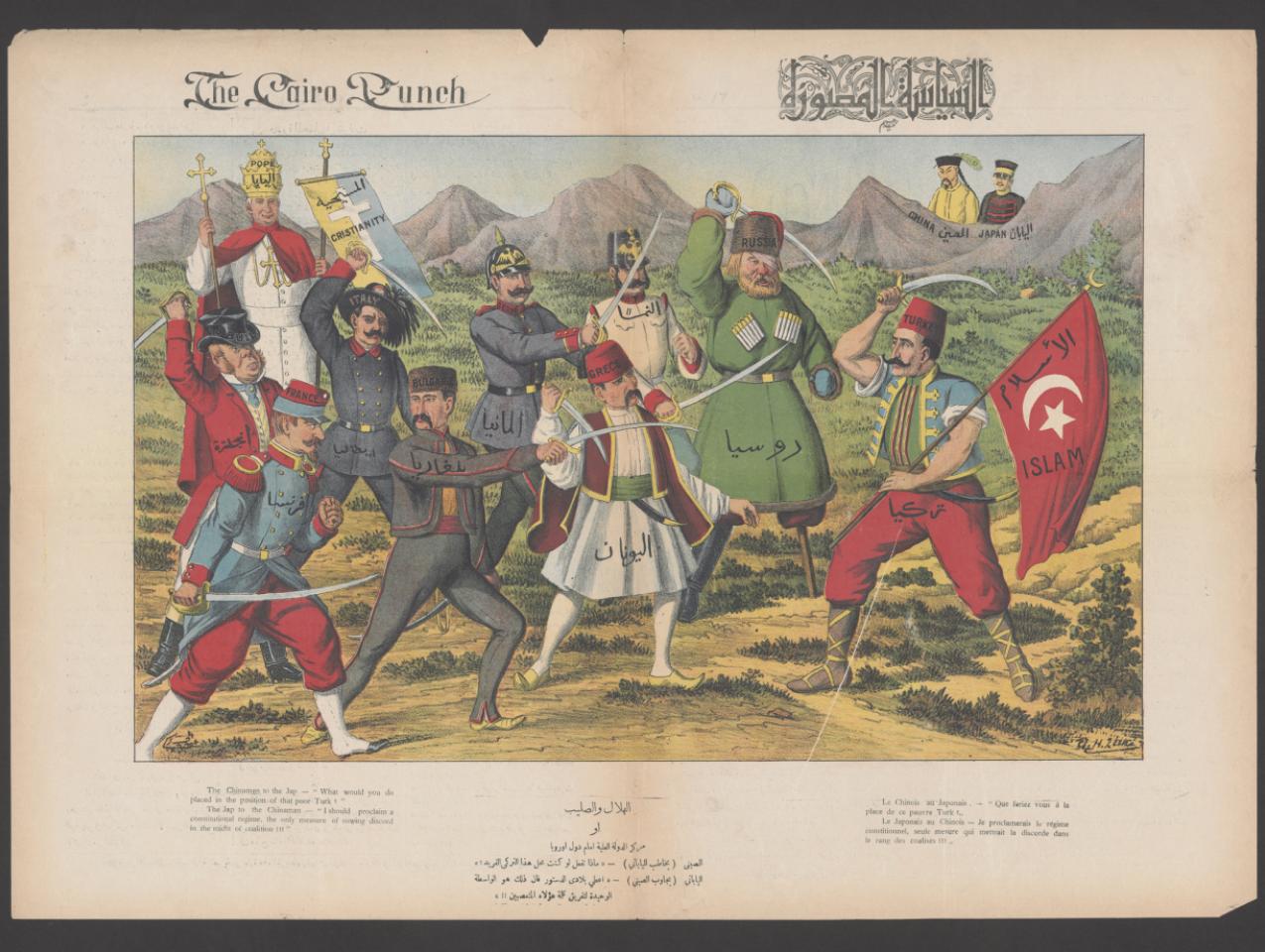

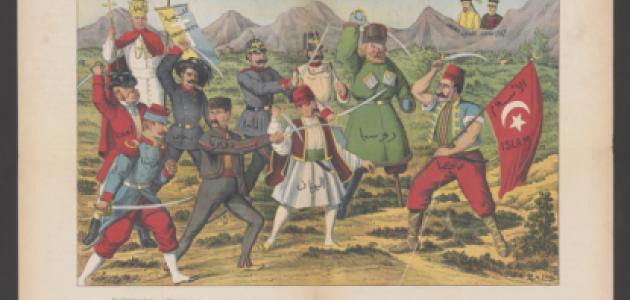

The Islamic State’s prospects for gaining broad acceptance across the Sunni Muslim world are low. Since the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924, repeated efforts to resuscitate the institution have foundered on tribal, ethnic, national, and ideological schisms. Mainstream Muslim scholars, intellectuals, and political leaders have denounced Baghdadi and his brand of Salafist Islam as heretical, and so have some from other extremist organizations, including al-Qaeda.

Conceivably, the respect that the Islamic State amasses through military victories and sheer survival could, in combination with concerted efforts to include non-Salafist Muslims, attract individuals of high repute within Sunni Islam. Given ethnic and national divisions, however, it is doubtful that such individuals would enjoy wide popularity beyond Syria and Iraq. Whatever political and cultural influence the Islamic State wields in the future, therefore, will most probably be limited to the sections of Syria and Iraq where its gunmen hold sway.

Whatever its limitations, the Islamic State could serve as an enduring platform for international terrorism. Its territory offers enormous opportunities for organizing terrorist actions and training foreigners whose passports give them easy access to the West. With the United States having slashed its military and forsworn stability operations, the Islamic State’s sponsorship or facilitation of terrorist attacks would not necessarily lead to its demise.