To a younger generation of political observers, California is the quintessential blue state. It’s Hollywood and San Francisco, medicinal marijuana and gay marriage, UC-Berkeley, the self-esteem movement, tree-sitters, the first majority minority state—a long list of liberal symbols that raise the ire of conservative commentators. To an older generation of political observers, however, the Democratic turn in California is a relatively recent development.

The picture is clearest at the presidential level. Consider the post–World War II victors: Harry Truman’s 1948 victory was the last hurrah of the New Deal—he carried California by one-half of 1 percent of the vote. There followed a noteworthy string of ten elections in which Republican candidates carried the state nine times, falling short only in the 1964 landslide by Democrat Lyndon Johnson. (In seven of the ten elections a Californian was on the Republican ticket.) In the 1980s national political commentators often discussed the Republican “lock” on the presidency, with California viewed as an important part of the lock. The Democrats picked the Republican lock in California (as in the nation at large) in 1992, with help from Ross Perot, who took almost 21 percent of the statewide vote. When more normal electoral conditions returned in 1996, however, the succeeding elections indicated that the Republican presidential era had ended: in the elections of 1996, 2000, and 2004, the Democratic margin averaged almost 12 percent of the vote.

Gubernatorial outcomes present a similar picture of California elections in the latter half of the twentieth century. Earl Warren first won office during World War II, won re-election twice (this was the era before term limits), and served until he was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Dwight Eisenhower. In the generation after Warren the only Democratic bright spots were the Edmund Browns, father and son. Since Warren’s first election the Republicans have held the governor’s mansion for 43 years, compared to the Democrats’ 21 years. Of course, until Arnold Schwarzenegger arrived on the scene in 2003, the post-1994 gubernatorial showings of Republican candidates were as poor as their presidential showings.

Elections for U.S. senator showed a slightly less Republican tilt than presidential and gubernatorial elections, mainly because of one Democrat, Alan Cranston, who won four six-year terms. Even so, in the 48-year period between the elections of 1944 and 1992, Republicans occupied California’s Senate seats for 54 senator years, compared to the Democrats’ 42. Since 1992, however, the Republicans have been shut out by Democrats Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, who will have held the state’s two seats for a total of 32 years by the 2008 elections.

This brief electoral history suggests two conclusions. First, until recently Republicans were more than competitive in California statewide elections. Indeed, for most of the latter half of the twentieth century California was, if not a red state, at least a reddish purple state. (The Legislature is another matter. It went Democratic in 1958 and has remained so since, with only two brief two-year interruptions in the Assembly.) Second, something happened in the 1990s to reverse party fortunes.

To many observers that something was Republican Pete Wilson’s 1994 gubernatorial campaign, in which he backed Proposition 187, an anti-illegal- immigrant initiative that passed overwhelmingly, only to be set aside later by the courts. According to conventional wisdom, Wilson achieved his short-term goal of re-election at the cost of the long-term prospects of his party—the state’s large and growing population of Hispanics reacted to Wilson’s support of Proposition 187 by moving to the Democrats.

The hold of this conventional wisdom, not only in California but nationally, became strikingly apparent in spring 2006 when political commentators drew attention to the congressional battle over immigration bills, especially provisions dealing with illegal immigration. A majority of congressional Republicans favored a strict immigration control bill dubbed “enforcement only.” Congressional Democrats and President Bush favored an “enforcement-plus” bill that coupled immigration control with a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants already in the United States. When compromise proved impossible, no legislative action was taken.

The issue divided both parties, but the lion’s share of the commentary focused on tensions within the Republican Party. The divisions were partly about principle, especially respect for law and order; partly about material interests, notably the needs of various business sectors for unskilled labor; partly about culture, especially nativist fears of an influx of Third World people; but especially about the conflict between opposition to immigration— whatever its basis—and pragmatic electoral considerations.

As noted in the Economist, “California’s Republicans are still suffering because in 1994 they backed Proposition 187. . . . That prompted a . . . rise in Latino voter registration—and the shutting out of Republicans from power in the state Legislature.” That view was widely echoed.

CONVENTIONAL WISDOM RE-EXAMINED

Conventional wisdom usually exaggerates, but in this case, it was more wrong than right. Of course, the importance of Latino voters in California has increased. The proportion of Latino registered voters has approximately doubled since the early 1990s. In addition, exit polls indicate that the Hispanic tilt toward the Democrats in top-of-the-ticket races has become more pronounced during the past decade. If a population group that supports your party is growing in size, and its tendency to support you in elections is increasing as well, then other things being equal, your party’s electoral prospects are improving. The Field organization has calculated that the average Latino contribution to Democratic margins in recent elections has increased from about 4 percent in 1994 to about 7 percent today. So, yes, the Democrats have gained from the growing Latino vote. But given the size of Democratic margins in many recent statewide elections, the 3 percent or so gain provided by Latino voters is only part of the story, in fact a relatively small part.

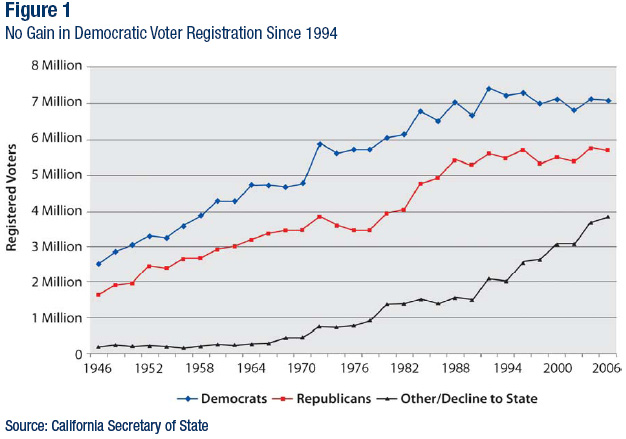

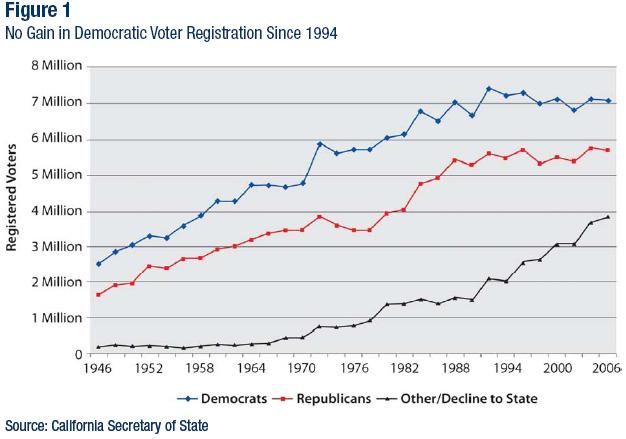

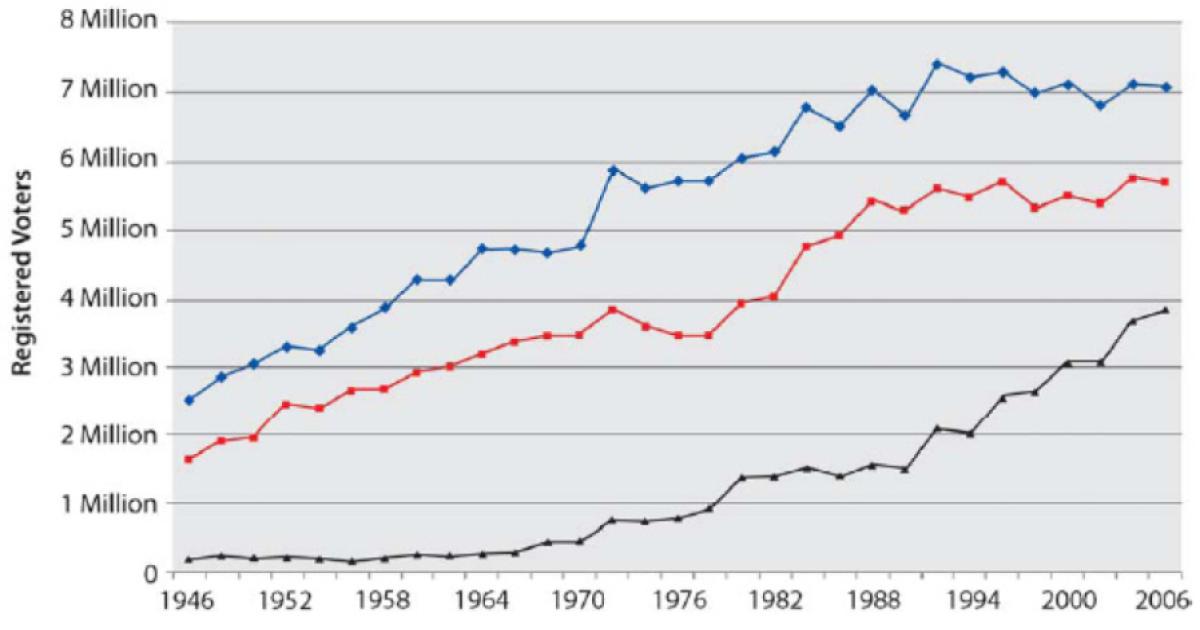

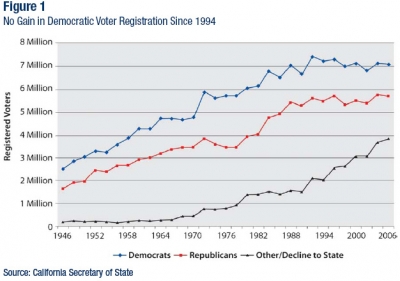

The larger part is that the “other things being equal” proviso has not been met. Figure 1 plots the number (not the percentage) of registered voters in California from the end of World War II to the present. Since Wilson’s 1994 re-election, voter registration in the state has increased by about 1.4 million. Surprisingly, however, Democratic registration has shown no net gain. Indeed, the number of registered Democrats was higher in 1994 than it has ever been—before or since. Thus the gains Democrats have made among Latinos since 1994 have been slightly more than offset by losses in other population groups. At the same time the number of registered Republicans has marginally increased, meaning that the Democratic registration edge today is only a little more than three-quarters as large as it was in 1994. In sum, looking at either the number of registered Democrats or the Democratic advantage relative to Republican, one reaches the surprising conclusion that in terms of voter registration the Democrats have lost ground since they began dominating statewide elections!

Where have the 1.4 million new registrants gone? A few have gone to established California minor parties such as the Libertarians, Greens, and Peace and Freedom, but nearly 95 percent of the net gain have gone to the “other/decline to state” category—independents (see bottom line, figure 1). Projecting the partisan lines provides the basis for Schwarzenegger’s 2006 decision to reposition himself as a “postpartisan” politician. A straight linear extrapolation from 1994 has the independents catching the Republicans in 2013 and the Democrats in 2016. Such trends, incidentally, are by no means unique to California. Twenty-five states that record voter registration by party report a surge in independent/nonpartisan registration between 2000 and 2004 averaging 21 percent, compared to 7 percent for Democrats and 5–6 percent for Republicans. In such deep blue states as Massachusetts and Connecticut, independents became the largest category of registered voters some years ago.

Another, less obvious feature sheds light on our main subject, the 1990s decline in Republican fortunes in California. Note that even during the long period when Republican candidates dominated the presidential voting and won senatorial and gubernatorial elections considerably more often than they lost, they never enjoyed a registration edge over the Democrats (see figure 1). Republican statewide victories were fashioned from some combination of two factors: holding their own party faithful at a higher rate than the Democrats held theirs, and winning the bulk of the independent vote. The first consideration clearly was more important forty years ago, when independent registration was tiny, but the second grew in importance as independent registration increased, and now appears to be the key to Republican prospects in California for the foreseeable future.

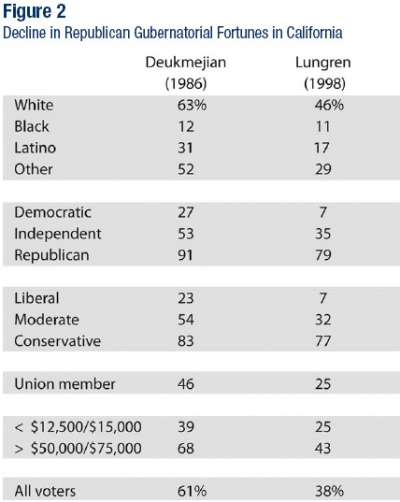

Compare the components of the Republican vote at the peak of party fortunes with its components at the nadir (see figure 2). Republican George Deukmejian won the 1986 gubernatorial election by 22 percentage points. Republican Dan Lungren lost the 1998 gubernatorial election by 20 percentage points.

Lungren’s share of the Latino vote was 14 percentage points lower than Deukmejian’s, according to exit polls. That much hews to the conventional wisdom. But Lungren’s share of the much larger white voter category was 17 percentage points lower than Deukmejian’s. Reading down the table, we see that Deukmejian held nine out of ten Republican partisans, whereas Lungren held only eight. But of even greater numerical importance than the 10 percentage point difference in Republican support, Deukmejian induced more than a quarter of Democratic partisans to cross over, while Lungren attracted less than a tenth of Democrats—a 20 percentage point difference in a larger voter category. Also, Deukmejian carried the independents in 1986; Lungren attracted barely a third of them—and the category was 50 percent larger by 1998.

Lungren fell only a little short of Deukmejian among self-identified conservatives, but while Deukmejian won almost a quarter of liberals, Lungren won less than a third of Deukmejian’s share. And where Deukmejian carried the moderates, Lungren won less than one-third of their vote. The selfidentified moderate voter category had reached almost 50 percent of the electorate by 1998.

The income data are perhaps the most striking. The once-overwhelming Republican support among affluent Californians had deteriorated to the point that a majority of them voted Democratic in 1998. The so-called party of the rich did not win a majority even among high-income households.

WHY THE REPUBLICAN DECLINE?

The evidence so far indicates that the movement of Latinos to the Democrats has been neither sudden nor massive in absolute terms, nor nearly large enough to explain the observed turnabout in party fortunes. Rather, Republican statewide candidates in the past decade have performed much worse than previously among political independents, ideological moderates, and even wealthy Californians.

Why did a California electorate that had supported William Knowland, Thomas Kuchel, and Pete Wilson for senator and Ronald Reagan, George Deukmejian—and again, Pete Wilson—for governor change its partisan

preferences in a relatively brief time? The most likely explanation is a change in the image of the California Republican Party and a change in the kind of candidate it nominates. A generation ago, it was a pragmatic, broad-based party that emphasized issues such as taxes and spending of concern to the broad middle of the electorate (and even to many on either side). It was a conservative party when conservative was defined largely in economic terms—low taxes, efficient public services, and limited government. Today, it is an ideological, narrowly based party that defines its conservatism by social and cultural issues like abortion and gay marriage that are of only secondary concern to most Californians. Moreover, most Californians take more liberal views on such issues than do California Republican activists.

The middle of the road in California runs through the economically conservative but socially tolerant quadrant of the ideological space.

The ten counties in which Republicans suffered the smallest and largest drop-offs in vote share between the 1986 and 1998 elections (the Republican vote fell in every one of the state’s 58 counties) are seen in figure 3. With the exception of fast-growing Kern and Fresno counties in the Central Valley, the counties with the smallest declines in Republican support are in the sparsely populated mountains and far northern timber and cattle lands. Most of the counties with the biggest declines lie in the San Francisco Bay Area, extending north to the wine counties of Sonoma, Napa, and increasingly Lake, east to Contra Costa County, and south to Santa Clara County (Silicon Valley). Many of these are densely populated and becoming increasingly so. Moreover, their residents are highly educated, affluent professionals, the kind of people who used to constitute the core of the Republican vote.

We surmise that the people who inhabit the counties with small GOP declines are more culturally conservative and therefore less likely to be put off by the contemporary Republican Party. But the wealthier the county, the larger the fall-off in Republican support. Evidently, middle- and upperincome Californians liked Republicans better a generation ago, when they stood for “leave us alone,” than today, when they stand for “do as we say.”

CONCLUSION

We conclude that Pete Wilson was framed. He was convicted of a political crime to which he was at most a minor accessory. After his 1994 campaign, both parties found it convenient to accept the circumstantial evidence. Why? For Democrats, attributing the Republican decline to alienated Latinos fits their stereotype of Republicans as bigoted, or at best unsympathetic to minority issues. Even better, Democrats could view the electoral losses suffered by Republicans as evidence that Republican callousness or prejudice had brought on just punishment.

But why would Republicans not search more carefully for the causes of their electoral misfortunes, meekly accepting an ethnic explanation that they normally contest when advanced by Democrats? The simplest answer is that it shifted the blame. It is much easier for ideological activists to blame their defeats on demographic and historical factors over which they have little control (“there are more and more Latinos and they don’t like us because of something that Wilson did in 1994”) than to accept that voters have looked at what they offer and rejected it.

More generally, what has happened in California appears to reflect what has happened in national politics in the past few decades. The Reagan revolution relied on a coalition of the economic and social branches of the conservative movement, and in its early years the economic branch dominated, as social conservatives periodically complained. Over time the balance shifted, however, until the public face of the party became dominated by social conservatism—anti-abortion, anti-gay, anti-stem cell research, as well as other minority positions like anti-environment. More recently, the fiscal profligacy of the 2001–06 Republican Congress has blurred any lingering image of the Republicans as the party of economic conservatism.

One cannot deny the political benefits of this ideological evolution to the Republicans nationally. Most obviously, it contributed to the realignment of the South, which led to Republican congressional majorities in 1994. But what some have called the “Southernized” Republican Party has much less appeal in California and the Western United States, where a more libertarian brand of conservatism has historically been stronger.

We suspect that in underlying attitudes and policy views the California electorate of 2000 is not much different from the California electorate of 1990. The reason statewide elections turn out so differently today is that the Republican Party offers voters a kind of candidate for whom they have less enthusiasm. In our view, California remains purple under its blue surface. Indeed, the Schwarzenegger phenomenon is evidence for that position. Rather than an anomaly attributable to his Hollywood persona, Schwarzenegger illustrates the kind of Republican who can win in California. Consider that in the 2006 elections more than three-quarters of a million Californians voted for Schwarzenegger, but one line lower on their ballots they declined to cast a vote for movement conservative Tom McClintock, the Republican candidate for lieutenant governor.

If the Republicans were again to nominate candidates such as Pete Wilson, Tom Campbell, Ed Zschau—and going back further, Ken Maddy and even Ronald Reagan—statewide elections would exhibit California’s traditional purple hue. But it is not clear that the Republican Party today even contains many such potential candidates, let alone is prepared to nominate them.