Changes to the tax code are frequent, but opportunities for fundamental reform are rare. The mid-1980s offered one such opportunity, when the Tax Reform Act of 1986 simplified the income tax, removed many tax distortions, and encouraged economic growth. On November 1, 2005, the President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform, of which we were both members, submitted its recommendations to the Secretary of the Treasury. The panel’s report detailed a number of fundamental changes that we believe move the economy in the direction of greater efficiency and enhanced growth.

Why Reform?

Many Americans believe that the current tax system needs to be reformed. They differ, however, on the aspects of the status quo that they find most objectionable and on the direction that they would like reform to take. Before discussing tax reform, it is important to identify the shortcomings of the current system. Without knowing the symptoms, it is difficult to specify the cure.

A tax system should generate the government’s required revenue with as little economic distortion as possible, while distributing tax burdens fairly. This raises a fundamental trade-off. The most efficient tax system is one that collects lump-sum taxes from each taxpayer, but such a system would be almost universally dismissed as unfair. Taxes that increase with various measures of a taxpayer’s ability to pay—such as total income, consumption, or wealth—create disincentives for income creation, spending, and wealth accretion. The challenge of tax policy design is balancing the efficiency cost of various revenue instruments (their deadweight loss) against the distributional benefits of taxes that vary with individual circumstances.

The current tax system imposes a number of costs on the U.S. economy. The most obvious is the cost of tax preparation, which most estimates place at more than 1 percent of GDP. The typical worker, including those in the tax preparation industry itself, spends the equivalent of two workdays per year engaged in the accounting and minutia required for tax filing. More than 60 percent of tax filers consult a third-party preparer for assistance with their return. Simplifying the tax system could reduce these costs. Additionally, because taxes create differences between pretax prices and after-tax prices, they change the incentives to save, to invest, and to work. The saving rate in the United States is extremely low, by both historical and international standards. Taxes on capital investment, at both the business and the investor level, drive a wedge between the before-tax and the after-tax return to saving and investing. Reducing the tax burden on investment would be very likely to increase investment relative to its current level. Some provisions of the current tax code create very specific distortions. For example, the differential treatment of debt and equity encourages firms to borrow rather than to use equity finance. The differential tax treatment of different types of business entities, such as C-corporations, S-corporations, partnerships, and LLCs, affects the choice of organizational form for business start-ups.

Labor supply is directly affected by tax rates. The adverse effect of high tax rates on labor supply is supported by evidence from the Tax Reform Act of 1986 as well as by evidence from other countries such as Sweden that have cut marginal tax rates on labor income. Human capital investment is affected by the progressivity of the tax system. When much of the cost of training and education takes the form of forgone earnings, highly progressive tax schedules that apply a higher marginal tax rate to the higher earnings that result from education than to the lower earnings that are forgone punish the acquisition of skills that are required in an advanced economy.

The panel concluded that an efficient tax system should remove distortions to the extent possible and that “social engineering” through the tax code should be avoided. It is possible to argue that some activities should be encouraged by the tax system, either because they create social externalities or because there are other distortions in the economy that could be offset by appropriate tax remedies. Such arguments are usually difficult to support with empirical evidence, however, and they lead to special privileges and myriad tax breaks that are likely, on balance, to reduce the efficiency of the tax system. Given the political process that determines the tax code, special provisions are likely to depend more on an interest group’s lobbying efforts than on careful estimates of social externalities or other considerations.

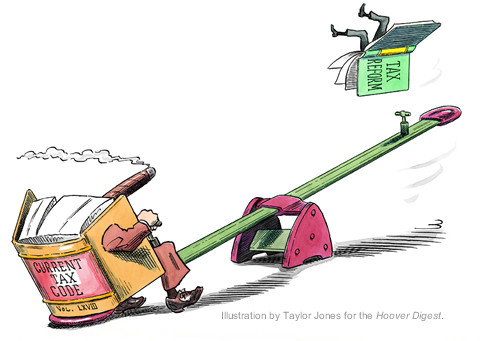

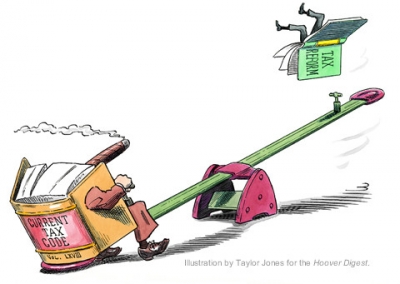

The Current Tax Mess

The 19 years since the passage of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 illustrate the role special interests play in the tax policy process. More than 15,000 changes in the tax code during that period have undermined many of the achievements of the 1986 legislation. They have created a tax code that is riddled with targeted incentives, phase-out rules, phantom tax rates, and complex and sometimes inconsistent provisions that leave most taxpayers unable to understand the rules under which they are taxed, let alone able to complete their own tax return. For example, there are at least five different definitions of child for various tax credits and other tax provisions. Families that are interested in saving for their future needs confront a confusing menu of possible saving vehicles, including 401(k)s, 403(b)s, 457 plans, 529s, IRAs, Roth IRAs, Coverdell saving accounts, and Health Saving Accounts. The tax system also favors some kinds of investments over others and discourages saving and investment overall.

The Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) is an important and growing source of tax complexity. The AMT is a parallel tax structure that operates in tandem with the individual income tax. Taxpayers compute their tax liability under two separate sets of rules and then pay the greater of the two amounts. This widely derided tax affected less than a million taxpayers in the late 1990s. Although the absence of inflation indexation provisions in the AMT ensured that it would affect a growing number of taxpayers over time, this process was hastened by the tax changes of 2001. The Economic Growth and Tax Reconciliation Act of 2001 reduced many taxpayers’ liabilities under the individual income tax, raising the likelihood that the taxpayers’ AMT liability would exceed their individual income tax liability. Congress has slowed the growth of the AMT by enacting temporary fixes that raise the AMT exemption level.

As a result, nearly four million taxpayers paid the AMT in 2004. If the AMT “fix” expires, however, as it is currently scheduled to do, the number of AMT payers will jump to 21 million in 2006. It will continue to grow in subsequent years, reaching nearly 30 million taxpayers by the end of the current decade. The AMT is most likely to affect taxpayers in large families in states with high state and local tax burdens, meaning that many Americans in these states face impending and surreptitious tax hikes.

Efficiency Gains from Tax Reform

Although many see simplification as the primary goal of tax reform, promoting economic growth is an even more important objective. Even in the relatively short run, the economic costs of a tax system that slows economic growth are likely to exceed compliance costs. Halving the costs of tax compliance would be equivalent to raising GDP by about one-half of 1 percent—no minor accomplishment. The growth in GDP that might result from reducing tax burdens on investment and shifting toward a consumption tax is much larger.

The current tax system taxes corporate income once at the corporate level and again at the investor level. This double tax was reduced by the 2003 tax reform, but the reduced tax rates on dividends and capital gains are scheduled to expire at the end of 2008. The Treasury Department estimates that, under current tax rules, the total tax burden on a new corporate investment project is 24 percent. By comparison, investments in the noncorporate sector, which are taxed only once, face a 17 percent tax burden. Investments in owner-occupied housing yield untaxed returns in the form of implicit rental income; thus their effective tax rate is near zero and may be negative.

A substantial body of economic research suggests that disparities between the before-tax and the after-tax return on new investment are particularly detrimental to long-term economic growth, as are differences in the relative tax burdens on different assets. The Treasury Department estimates that eliminating the tax burden on new investment, for example, by adopting a consumption tax, would eventually raise GDP by between 5 and 7 percent. GDP growth is essential to improving the standard of living for all Americans, and it is closely tied to productivity growth. As productivity rises, compensation tends to follow, even over short time periods. The surest way to raise wages is to raise productivity.

Options for Tax Reform

Tax systems are broadly classified as income based or consumption based. Income taxes apply to both labor earnings and capital income. Consumption taxes apply to spending, and they do not tax the return to saving or investment. Our current tax system is a hybrid that falls between the two. It taxes income from capital but allows substantial tax relief for some types of saving. Pension plans, IRAs, and many other specialized programs that allow families to save without paying tax on their investment returns introduce consumption tax elements to the income tax structure. Most economists favor consumption taxes over income taxes as long as they can be made appropriately progressive. A “textbook” consumption tax is neutral across all types of spending. By eliminating the favored treatment of present consumption over future consumption that results from the taxation of saving in an income tax, a consumption tax removes the disincentive to save.

The panel endorsed two reform proposals that would improve economic growth, simplify the tax code, and roughly preserve the current distribution of tax burdens. Both proposals would repeal the individual and the corporate AMT. The first is the Simplified Income Tax. It preserves the income tax framework but cuts marginal rates to 15, 25, and 33 percent. It provides for a large amount of tax-free saving, consolidates credits, and rationalizes the system of business taxation.

The second reform proposal, the Growth and Investment Tax, builds on the Simplified Income Tax system but shifts toward a consumption tax by allowing the full expensing of capital. All business entities would be taxed in the same way, thereby eliminating tax-induced distortions to organizational form. Nonfinancial businesses would be taxed on a cash-flow basis, and financial income or outflows, including principal and interest, would be ignored for tax purposes. The business tax rate and the top individual income tax rate would be 30 percent. The Growth and Investment Tax would differ from a pure consumption tax in one important way: Household receipts of interest, dividends, and capital gains would be taxed at a flat 15 percent rate.

Productivity growth depends on investment in human capital, physical capital, and intangible capital. Investment in human capital means acquiring skills through formal education and learning on the job. Investment in physical capital means adding to the stock of plant and equipment that makes workers more productive. Intangible capital includes the stock of research and development and other factors that make both physical and human capital more productive. Both the above proposals encourage investment in skills by reducing marginal tax rates on labor supply for most earners. Both proposals encourage investment in physical and intangible capital by reducing the tax wedge between the before-tax and the after-tax returns to new investments. The Treasury Department estimates that moving from the current structure to the Growth and Investment Tax would lower the average tax burden on all investment from 17 percent to 6 percent. This would encourage new investment and could significantly increase productivity and wage growth.

In a global capital market, a nation’s saving and its investment need not be equal, but they are linked. When a nation’s saving is low, investment can remain high if the returns to investment attract foreign capital. Low tax rates on investment encourage foreign investment. But in the longer run, a nation’s standard of living will grow more quickly if it owns the capital that raises its productivity because it then benefits not only from the higher wage growth that results from using the capital but also from the capital returns. The current U.S. tax system discourages saving. Both the proposed plans reduce the total tax burden on saving and investment, thereby promoting long-run economic growth.

Eliminating Deductions

Both proposals trim many of the deductions that currently narrow the income tax base but retain incentives for charitable giving, homeownership, and the purchase of health insurance. Both proposals allow taxpayers a deduction for their charitable contributions in excess of 1 percent of taxable income. Both proposals replace the current itemized deduction for interest on a mortgage of up to $1 million, plus a $100,000 home equity loan, with a 15 percent tax credit on interest for loans up to 125 percent of an area’s median home price, computed using the FHA’s loan limits. Less than 5 percent of households nationwide have mortgages that exceed the new limit. Lowering the cap on tax relief for mortgage borrowing would preserve incentives for homeownership while reducing the tax incentives for households to purchase larger and more-expensive homes than they would purchase in the absence of tax incentives. Many homeowners who do not currently itemize their deductions will receive tax relief under these plans.

Neither plan adopts the most conceptually attractive approach to the taxation of owner-occupied housing, which involves estimating the imputed rental value of every home and including this in taxable income. The administrative feasibility of designing a tax on imputed rent warrants investigation as an alternative method of narrowing the effective tax-rate differentials between housing and other assets. Because housing services remain untaxed whereas some mortgage interest qualifies for a tax credit, housing would continue to be less heavily taxed than other investments under both plans, but the differential between housing and other investments would be reduced. This leveling of the playing field across different asset categories would promote a more efficient allocation of capital.

Employer-provided health insurance is currently untaxed regardless of its cost. This encourages the purchase of excessively generous insurance policies. To preserve incentives for employers to provide families with basic insurance coverage, both plans exempt employer-provided health insurance valued at less than $11,500 for a married couple, and $5,000 for a single individual, from income taxation. When employers provide policies that cost more than these thresholds, the cost in excess of the threshold will be included in taxable income.

Both plans eliminate the federal tax deduction for state and local income and property tax payments. Although residents of high-tax states will surely protest these changes, under the current tax system, many of those same deductions will be eroded as the AMT expands its reach.

Both plans provide for a gradual transition to new provisions where abrupt changes might cause hardship. For example, interest deductions on current mortgages and depreciation allowances on past investments would be grandfathered and phased out over time.

The Distribution of Tax Burdens

Both reform proposals leave the distribution of the burden of paying for the federal government virtually unchanged. Because many of the tax deductions that are capped or eliminated under the plans are used more extensively by high-income than by low-income households, even though top marginal tax rates fall, there is a small increase in the tax burden on households in the top quintile of the income distribution. This group’s standard of living would still rise in the long run as a result of the plans’ favorable effects on long-term economic growth.

The panel made a conscious attempt to adjust rates and break-points so as to preserve the current distribution of tax burdens. This distribution reflects outcomes chosen by elected officials and can be thought of as the equilibrium of a political process. As such, the panel did not feel comfortable recommending changes in the distribution of tax burdens. Of course, it would be straightforward for Congress to change the distributional burden of the proposed plans by altering rates and break-points. But Congress should bear in mind that changing the structure of tax rates to achieve a particular burden distribution may have consequences for incentives on many margins, such as labor supply and investment in human capital.

Revenue Neutrality

The executive order that created the President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform required reform options to be revenue-neutral. The Bush administration’s revenue baseline for the next 10 years assumes that the tax cuts of 2001, 2003, and 2004 are permanent. Many have criticized the panel for using this baseline, rather than creating a separate baseline that made different assumptions about the future course of fiscal policy. Some have suggested that the plans raise too little revenue, whereas others worry that the proposals build in an implicit tax hike.

The panel followed the president’s instructions to offer only plans that were revenue-neutral. Rather than debating the appropriate level of taxation, which is for the president and Congress to decide, the panel focused on the structure of the tax system so that the basic plans could be used to raise different levels of revenue by changing marginal tax rates. Although the panel was told to assume that the president’s tax cuts were permanent, we were not given any instructions with respect to revenues associated with the AMT. We assumed that current law, which provides no relief from the AMT after 2005, would hold. Does that represent an implicit tax cut, a tax increase, or neither? The answer depends on what one believes about Congress’s likely behavior in the absence of tax reform.

Each recent Congress has enacted a one-year “patch,” in the form of an increase in AMT exemption levels, to avoid rapid growth in the number of AMT taxpayers. In the absence of any short-run fixes, that exemption level would be $43,000 per year, but Congress raised it to $58,000 for married joint filers in 2005. Were the exemption level allowed to fall by $15,000, federal tax revenues would rise substantially and many more taxpayers would face the AMT. The tax increase associated with expiration of the AMT patch is built into the revenue baseline used by the panel.

The revenue effects of the tax-rate reductions in 2001, 2003, and 2004, and of the AMT patch, are of roughly the same magnitude. Absent fundamental tax reform, if Congress made the tax cuts permanent but also allowed the AMT patch to expire, then aggregate revenues over the next 10 years would be close to those assumed by the panel’s revenue baseline. If one thinks the status quo involves a scenario in which Congress would have taken rates back to their 2001 levels but continued to patch the AMT, status quo revenues would be higher than those projected under the baseline that the panel assumed. If, instead, Congress would both extend the AMT patch and make the president’s tax cuts permanent in the absence of reform, then the proposed plans represent a tax increase relative to the status quo. We believe that the panel’s position is both realistic and appropriate and that it reflects neither a tax cut nor a tax increase relative to what would likely occur without reform.

The Whole Is Greater Than the Sum of the Parts

Tax reform, as distinct from tax reduction, inevitably involves curtailing some entrenched tax benefits. If reform proposals are dissected by politicians in an attempt to promote provisions that reduce their constituents’ tax liabilities while excising those that might lead to higher taxes, then reform will inevitably fail. But if reform proposals are viewed instead as a collection of provisions that taken together leave most families in a position not very different from their current one, while also shifting the tax system toward a structure that will promote long-term economic growth and reduce the burden of tax compliance, then these proposals can command broad popular support and even enthusiasm. Genuine tax reform is a difficult process that requires commitment to the goal of creating a more efficient, simpler, and fairer tax system.

The President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform submitted its proposals on November 1, 2005. Exactly 240 years earlier, the Stamp Act took effect in the American colonies. It was neither fair nor simple, and, by slowing commerce, it reduced economic growth. Like the colonists who demanded the repeal of the Stamp Act, current-day Americans should demand relief from the burdens imposed by today’s tax code. The panel has offered proposals that will, like abolition of the Stamp Act, improve our tax system and our economy.