- K-12

- Education

A Nation at Risk, published in 1983 by the National Commission on Excellence in Education, galvanized attention to low student achievement as the critical issue in America’s schools and launched an attack on the problem that has been sustained to this day. In this way, A Nation at Risk was a watershed. Never before had schools been asked to focus as sharply on improving student achievement. And never before had policymakers worked as hard to help—or force—schools to deliver. Thus the 1980s quickly brought tougher graduation requirements, more academic course taking, higher teacher salaries, and more training for teachers. The 1990s added rigorous statewide academic standards, extensive standardized testing, and accountability. In 2002, the federal government mandated testing in reading and math in grades three through eight nationwide.

These are major changes, and, in their sheer focus and commitment to doing education differently, some might even call them revolutionary. But they do not in fact constitute a revolution. For they leave intact a fundamental obstacle to major improvement, which is the system that provides public education in the first place. A Nation at Risk clearly believed—and it stated so explicitly—that through goodwill and hard work, the American education system could deliver on the changes recommended in the report. A Nation at Risk did not raise a single question about the capacity of the education system to get the job done. But in the years since A Nation at Risk, such questions have been asked with increasing frequency.

Reformers have argued, in particular, that public schools cannot be easily counted on to raise achievement or easily forced to do so. They cannot be counted on because there has traditionally been no effective accountability. Schools that do not deliver better results for kids are almost always, and inevitably, allowed to continue delivering inadequate results. Yet the very mandates that would force schools to deliver better results—what to teach, how to teach, how to assess, how to re-teach, and so forth—tend to bog schools down, preoccupying them with following rules instead of encouraging them to solve problems and produce results. Reformers are faced with the dilemma of finding ways to promote accountability for results without destroying the initiative or autonomy of schools.

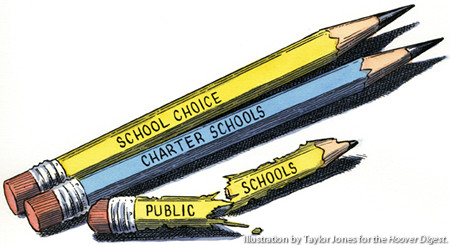

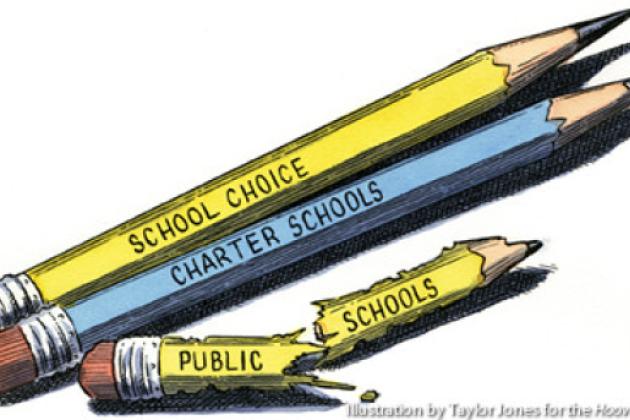

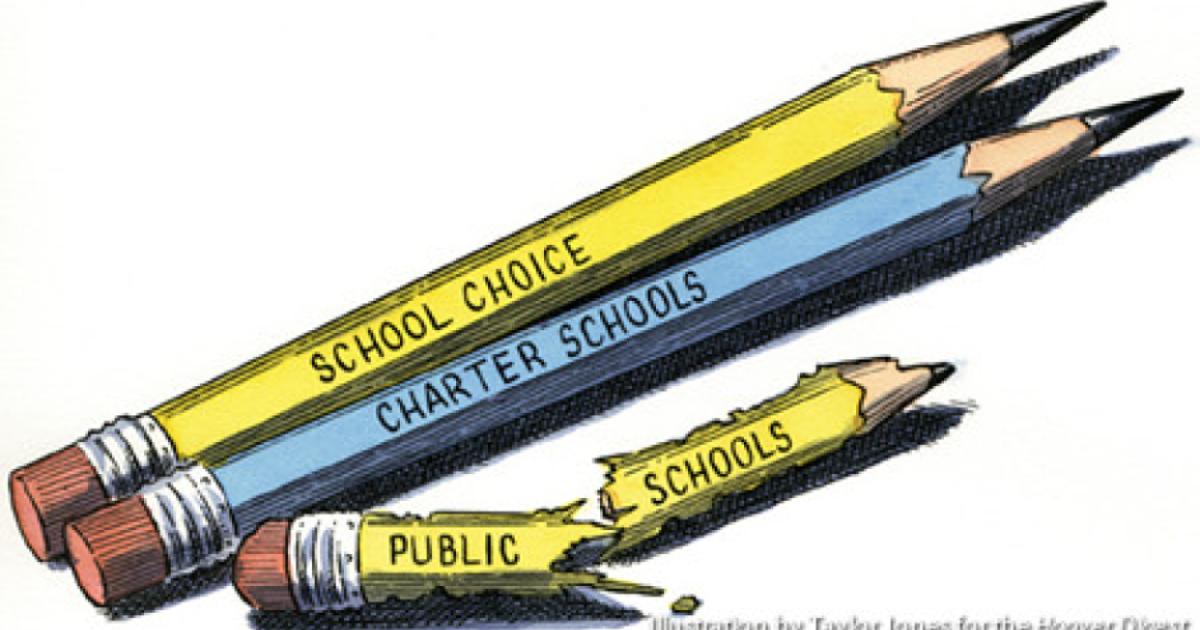

To resolve this dilemma, reformers have begun looking beyond the traditional education system for answers. A broad and fundamental reform strategy has taken hold in the years since A Nation at Risk that aims to inject the market forces of school choice and competition into the traditional system, which is based on very different principles—essentially, authority and control. By giving parents the right to choose the school their children attend and forcing schools to compete for enrollment—or risk closure from lack of students and funds—market-oriented reforms aim to improve schools by revolutionizing the system of which they are part. Under a system with market forces at work, policymakers need not micromanage improvement. Instead, they can focus on setting standards, testing for academic progress, and providing parents with information on school performance so that they can make good choices. The market can do the rest. Schools that do not raise test scores will lose students to schools that do. And the innovations necessary to boost achievement will emerge from the competition among existing schools. Those with the best ideas and practices will survive and be imitated.

A Decade of Reform

When A Nation at Risk was published, school choice was scarcely more than an academic notion. By the 1990s, however, a powerful combination of significant educational research and a changing political climate had laid the groundwork for serious reform. The time was ripe for market-oriented reform, if not for revolution. Over the course of the decade, American education saw a veritable explosion of choice-based initiatives on three fronts: private school vouchers, charter schools, and privately managed schools.

• Private school vouchers. Enactment of the nation’s first major voucher program came in 1990 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Despite modest beginnings, by decade’s end 10,000 students were participating in Milwaukee’s program. An equally successful and significant voucher program followed in Cleveland, Ohio. But these successes have not inspired similar successes nationwide. Vouchers remain a highly controversial idea, opposed tooth and nail by teachers unions. But sluggishness on the policy front has led philanthropists in many major cities to provide vouchers—called scholarships—to economically disadvantaged students. Combined with the students in the Milwaukee and Cleveland programs, in 2002 fully 60,000 students across the United States were attending private schools, with public or philanthropic support, instead of public schools.

• Charter schools. Charters emerged as both as a compromise between market advocates and opponents and as an ingenious idea in their own right. They provided a mechanism to produce competition and choice in public schools without turning to private schools and have thus become the most favored approach to market-oriented reform in America. In 1991, Minnesota became the first state to authorize charter schools. By 2002, a whopping 2,700 charter schools were operating in 36 states, enrolling 575,000 students. In just 11 years of operation, charter schools have enrolled 10 percent as many students as private schools—and private schools have had a 200-year head start!

• Privately managed schools. Scarcely an idea when A Nation at Risk was published, by 2002 private for-profit firms were running an estimated 370 public schools in the United States. Forty companies were in the business of education management in 2002, of which 36 actually managed schools. The largest by far is Edison Schools, which managed more than 100 schools with 73,000 students in 2001. Private management is an important development for school reform, of both the choice and the accountability varieties. Private management has the potential to bring to education some of the classic benefits of the free enterprise system but in completely new ways.

Market Essentials

If market-based reform is to realize the potential it has begun to demonstrate in the years since A Nation at Risk, policymakers must take additional measures both to promote it and to guide it. Markets are not perfect. Given the chance, they can be powerful engines for change, bringing to education the kinds of benefits they have brought throughout the free enterprise system. But markets must be carefully watched if they are to be fair and effective. This is particularly true for a public good such as education, where the government is paying for the service, the benefits are for society as well as for individuals, and the risks of inequity—already so prevalent in public education—are high. Accordingly, policymakers should follow a balanced course, advancing education markets while regulating them for the common good.

The following steps should be part of any such course:

1. States must continue to develop accountability systems for public schools. Such systems should include ambitious and explicit academic standards—for content as well as skills—coupled with standardized tests at every grade level to measure schools’ success in meeting them. The federal No Child Left Behind law, enacted in 2002, will encourage progress in this direction, but state policymakers should not be satisfied with testing only reading and math, as the law requires, or settling for tests that measure only basic skills, a danger with the tests that are now commonly in use. Accountability systems must also include meaningful rewards and sanctions.

No Child Left Behind will push states in the proper direction, but states must find ways to motivate more than just their worst schools, the focus of the federal legislation. Strong accountability systems are vital in a world with freer education markets. If schools are to be freed from much of the top-down control that now frustrates them, they must be held to tough performance standards.

2. States must develop information systems to report thoroughly and publicly on the performance of every school. Many states have begun this process with the publication of school “report cards.” This practice is essential to the workings of an education system with substantial school choice. Families are more likely to make wise choices among schools if they know how schools perform. For every school, states should report standardized test scores, college entrance exam scores, graduation rates, and student attendance. States should report how a school’s test scores and test score gains compare with the scores and gains of demographically similar schools locally and across the state. States should also provide information that might bear on the ability of the school to do a good job—for example, the percentage of teachers with degrees in the subject they are teaching and the teacher attendance rate. Opponents of school choice worry that only savvy parents will make good choices. States can ensure that all parents can make good choices by providing them with the right information. If schools are totally transparent, they will also be more sensitive to improving their performance.

3. States should take all necessary steps to enable charter schools to compete vigorously and fairly with the public schools run by school districts. States should remove all limits on the number of charter schools that may operate in a state or locale. Let families and the marketplace decide what the right number of charters should be. If traditional public schools are doing their jobs, charters will not grow explosively. States should not give local school systems the ability to veto charter applications within their jurisdictions. States should allow public bodies not tied directly to the education establishment—for example, public universities—to grant charters. States should support charter schools at the full per-pupil level of traditional public schools, including all local, state, and federal aid, general and categorical. And, finally, states should provide charter schools with per-pupil capital funds. The biggest impediment to charter school growth is facilities: Most states force charter schools to pay for facilities out of operating funds, a severe disadvantage in their efforts to compete with traditional public schools, which receive capital budgets for facilities.

4. To enable traditional public schools to compete effectively with charter schools, states should relax the regulations governing curriculum, textbooks, teacher certification, staffing, minutes of instruction, and anything else that is substantially relaxed for charter schools. In the end, health and safety regulations, nondiscrimination requirements, and academic standards should make up most of the state regulatory regimen. School districts can decide for themselves whether to change local regulations. States should lead the way in ensuring that all schools have the flexibility they need in order to innovate and succeed. In opposing choice, traditional public schools have often argued that the regulations they face make competition unfair. Precisely: Let’s give all schools the flexibility to shape their programs in the best interests of their students and compete for their support.

5. Any effort to revolutionize American education by putting more power in the hands of parents and less in the hands of system authorities would be foolish to overlook the country’s rich resource of private schools. Roughly one in nine students in the United States is educated in a private school. Most of these schools educate a cross section of students and operate for a fraction of what public schools spend. Catholic schools are a prime example. In America’s inner cities, private schools offer the only immediately available alternative to district schools. Charter schools will spring up in time. But, meanwhile, states should provide vouchers for private schools. The vouchers should be carefully structured to ensure that private schools serve the public interest as effectively as possible.

It is a common misconception, promoted by voucher opponents, that vouchers will promote inequity or reward unscrupulous or offensive operators. But the fact is that vouchers can be designed to work however policymakers want them to work. In this spirit, vouchers should be limited to low-income families since they are the ones who need choices the most. The vouchers should be for use in religious as well as nonsectarian schools since religious schools predominate and the purpose of voucher policy is to increase the supply of alternative schools. The voucher should be for less than the per-pupil allocation for charter schools—say, 15 percent less—since the objective of the market-based reform proposed here is to promote charter school growth, not private school growth. Private schools that accept vouchers should also be required to take them as payment in full for their services: Private schools should not be permitted to discriminate against families unable to top off the tuition with personal funds. Private schools should also be required to administer whatever tests are part of the state accountability system if a majority of a school’s students attend with the benefit of vouchers. Private schools should not, however, be held to any other accountability standards that might apply to charter schools. The state should accept the value of their private status as an alternative arena for school innovation. In an education marketplace brimming with information, private schools will need to convince families of their worth. Private schools should therefore be trusted to provide ample information about their performance.

Conclusion

The kinds of gains in student achievement that A Nation at Risk insisted the country must bring about have obviously not taken place. The reasons for this are many, but among them is the continued reliance of policymakers on the traditional school system to make the gains happen. Meanwhile, policymakers have begun extensive experimentation with an idea—choice—that has the potential to bring about much more meaningful improvement. These experiments are changing the politics of school reform, building constituencies of satisfied families who would be unwilling to return to traditional schools, and creating demand for more choices among those families who are dissatisfied with existing schools but unable to get into the scarce alternatives. They suggest that a revolution may yet be in our future.

Policymakers would do well to heed the above recommendations as they respond to the continuing demand for improvement. They would do well to recognize that market-oriented change takes time and that the reforms enacted over the last decade must be given the time to prove themselves—or not. These recommendations are not mere school reforms; these recommendations promise fundamental change in the way the American education system operates. They promise to strengthen public education by making it more accountable for student achievement, more attentive to the wishes of families, and more innovative in its use of scarce resources. They promote the influence of market forces but keep democratic authority ultimately in control, regulating the market for the public good. And, finally, as we reflect on the significance of A Nation at Risk and ask whether the gains in achievement that it challenged us to make will eventually be made, the answer will depend less on the progress of reforms that it advocated and more on the progress of reforms it failed to anticipate altogether.