- International Affairs

KABUL—“You are very fortunate to see Kabul at this moment of incredible change,” the earnest Afghan exclaimed. “Right now you’re seeing a country that looks like Germany after World War II—but in 10 years this place will look like Dubai!”

Given the level of destruction I had seen during my October visit to Kabul, I found the man’s prediction preposterous, but I tried to contain my disbelief. Kabul does indeed resemble photographs of Dresden taken at the end of World War II. Yet the thought that this bombed-out shell of a city could become another Dubai—the oil-rich emirate full of gleaming modern skyscrapers and high-end shopping malls—seemed nearly unimaginable. Nevertheless, the enthusiasm of the speaker—a returning émigré from California working for a mobile phone company in Kabul—was infectious. Indeed, it is the resilience and optimism of the locals (and returning émigrés) that prevents one from becoming overwhelmed by the utter devastation.

The Aftermath

Much of Kabul is a wasteland. The destruction from two decades of war is staggering. An estimated 78,000 houses were destroyed during the fighting, leaving much of the city in ruin. The majority of the destruction occurred during the factional fighting of 1992–1996—when various regional powers fought for control of the city—rather than during the Taliban reign or the American bombing campaign of 2001. (The Taliban “focused more on destroying culture, not buildings,” according to an Afghan American woman working for a

nongovernmental organization.) Kabul is situated in a dusty valley surrounded by mountains, so factions fighting to take the city would position themselves on opposing sides of the valley and shell the city, leaving massive destruction in their wake.

Whole blocks have been leveled. Squatters occupy tent cities and partially destroyed buildings—many without roofs. Electricity is spotty, with most residents having no more than 12 hours of power a day. (Some shopkeepers rev up gas-powered generators to light up their shops when they see potential customers approaching.) The hills surrounding Kabul are dotted with makeshift cemeteries, with green flags marking the graves of war victims. There are rarely names on the tombstones, and, in many cases, piles of large rocks are used as grave markers.

The devastation is even worse in the Shomali Plain region to the northwest of the capital, which was the site of intense battles between the Taliban and the Northern Alliance. The rough, pot-holed road through Shomali is still lined with dozens of bombed-out tanks and trucks, as well as markers indicating whether or not minefields have been cleared.

Tribalism is, of course, notorious in Afghanistan. To punish the largely Tajik population for its suspected loyalty to the Northern Alliance, the Pashtun-dominated Taliban conducted a scorched-earth campaign in the region, leveling every building in sight for miles, destroying irrigation systems, burning vineyards, and planting mines. An estimated 200,000 people fled the Shomali Plain during the years of fighting, and in many villages nothing remains but the ruins of mud-brick buildings.

Picking Up the Pieces

Yet even in the Shomali Plain there are signs of restoration. Large numbers of refugees have returned to reclaim their land and rebuild their crumbled homes, and Afghan mine-sweeping teams are slowly clearing the area. (It is expected to take 12 years to clear the hundreds of thousands of landmines in Afghanistan.)

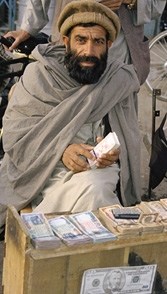

In Kabul, too, there are many signs of renewal. The markets are teeming with vendors hawking goods. During rush hour, the streets are a chaotic mess, with fleets of U.N. and relief agency Land Cruisers, Toyota taxicabs, Pakistani trucks, bicycles, and carts (pulled by horses, donkeys, or men) all competing for space. Soccer players practice in the stadium where the Taliban used to hold public executions. And children can be seen throughout the city flying kites—one of the many activities prohibited during Taliban rule.

Most encouraging, perhaps, is the fact that schools have once again been opened to girls—and that they have returned in large numbers. Estimates are that roughly half the school-aged girls in Kabul are now attending school, although that number drops to 10 percent in the conservative south of the country. During my visits to several schools, the girls said time and again how pleased they were to be back after being denied schooling during the Taliban years. Many female students had only recently returned from Pakistan, where they had been attending school after fleeing Afghanistan’s civil war. Although others had been taught secretly in private homes in Kabul, many simply did not attend school during the six-year Taliban reign.

Like much in Afghanistan, the schools are dilapidated. Many do not have desks and chairs, so students often sit on the ground all day, sometimes on dirt floors. One school built during the Soviet occupation was not large enough for all 6,500 students (all but 700 of whom are girls), so UNICEF-supplied tents were set up in the back where classes for the younger grades were held. For high school students, the curriculum is rigorous: advanced mathematics, chemistry, Dari and Pashtu (local languages), English, history, geography, and religious studies.

What Next?

Dr. Masooda Jalal is known in Kabul as the woman who challenged Hamid Karzai for the presidency during last June’s Loya Jirga (the “grand council” that elected the new government). She received the second highest number of votes and is considering running again. In her office at the World Health Organization compound in Kabul, Jalal speaks passionately about the hardships facing her country. When asked what the most critical problems and needs of the country are, she responds, “All the problems are number one. What is the priority? I say everything.” Indeed, the challenges facing Afghanistan are nearly overwhelming. As the Economist recently reported, the country remains in critical condition: “Things have not got better so much as less bad.”

So what is next for this war-ravaged country? The international community continues to pledge billions toward reconstruction efforts, although the funds are not moving in nearly as fast as everyone agrees they need to. Thus far, much of the money has gone toward emergency relief efforts, rather than toward reconstruction, and most of it has gone directly to nongovernmental relief agencies, with very little going directly to Afghanistan’s new government.

President Hamid Karzai’s central government continues to be weak and cash-strapped, with its authority barely extending beyond Kabul. Warlords still run virtual fiefdoms in much of the country and show little willingness to relinquish power. (Karzai recently complained to a British journalist that the warlord Ismail Khan was collecting millions of dollars in local customs duties in the western city of Herat while the central government could not even afford to pay teachers their salaries of $16 a month.) Outbreaks of violence occur sporadically throughout Afghanistan, and suspicions run high that the fanatically anti-American warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar has allied with remnants of the Taliban to create chaos in the country.

“Nation-Building Lite”

Complicating all this is that the 4,800 international peacekeepers—the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF)—have been constrained to Kabul, largely at the insistence of the United States. In recent months, the Bush administration has withdrawn its outright objections to ISAF expansion, but the momentum and interest of the international community in enlarging the force seem to have waned. Many in the foreign policy community argue that the expansion of ISAF throughout Afghanistan is critical for security to be maintained and for Karzai’s fledgling government to consolidate power, yet the Bush administration appears profoundly ambivalent about “nation-building” and seems reluctant to see a significant expansion of peacekeeping functions in Afghanistan. Writer Michael Ignatieff has criticized the U.S. approach as “nation-building lite,” and he and others argue that much more must be done to prevent Afghanistan from once again descending into civil war and chaos.

The big fear of Afghans is that the country will again be abandoned by the international community—particularly given the Bush administration’s current focus on Iraq. As a journalism professor at the University of Kabul warned, to the nodding agreement of his colleagues, “If the Americans leave, the bandits will immediately come down from the hills.”

Larry Goodson, a specialist on Afghanistan at the U.S. Army War College, agrees that an active American involvement in rebuilding the country is vital. “With nation-building as with peacekeeping, there are no shortcuts and no substitutes. Either the world helps this crippled nation to heal and rebuild, or it is sure once again to become a lawless haven for criminals.”