- US Labor Market

- Contemporary

- Law & Policy

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Civil Rights & Race

- Economics

- History

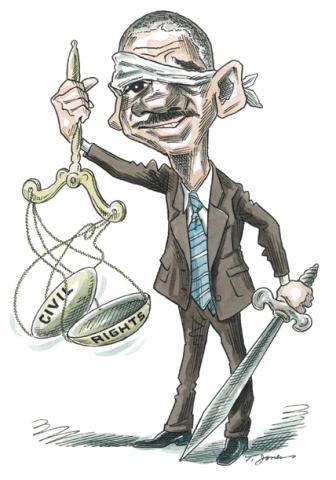

Attorney General Eric Holder has recently signaled on several occasions that the Department of Justice intends to reverse the policies of the Bush administration by beginning a new era with more vigorous enforcement of the civil rights laws. As the DOJ seeks to hire more lawyers in its Civil Rights Division, it needs to chart out a precise course of action—but how?

Let’s go back to first principles: should the United States have civil rights laws at all? In some cases, the answer is an emphatic yes; it is a travesty of justice to exclude eligible voters from the polls because of their race, sex, or national origin.

But today we face the March of Dimes problem of what to do now that this battle has been largely won. The follow-on disputes are much more vexing. Should the DOJ attack the more stringent state requirements, such as presenting drivers’ licenses to establish voter eligibility? Given the state interest in fraud prevention, Justice Stevens—take note—denied a challenge to the Indiana motor-voter law in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board. He has a point; there are weighty interests on both sides. The balance of advantage is too close to call for the Holder DOJ to treat this issue as a high priority.

While pondering motor-voter laws, Holder should confess error in Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder, in which the Supreme Court tiptoed around the DOJ’s attempt to impose an onerous and ill-designed preclearance provision of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act against elections held by a utility district. Those procedures, as updated in 2007, impose preclearance requirements on all districts in states with a pattern and practice of discrimination in (yes) 1972 for the next twenty-five years, no less.

Every justice entertained serious doubts about the constitutionality of a statute that cuts so deep into local prerogatives for so little reason. Holder should not let the issue remain in limbo just because the Supreme Court ducked the constitutional issue. The DOJ should declare unilateral surrender, either by administrative order or, if need be, legislation; today’s new statutory reference point should be 2008, not 1972, and that new starting point should be brought forward at least every ten years.

How then should the DOJ devote its newly released resources? The key choice is whether to investigate alleged abuses by private or public bodies. Choose the latter. Perhaps the great mistake with the 1964 Civil Rights Act was to legislate as if public and private discrimination posed equal social threats. That approach made sense when Jim Crow forced private businesses to segregate on racial lines, but today’s affirmative action, when voluntary, can aid the cause of racial integration without government coercion.

So let the DOJ do the legal minimum by pursuing explicit cases of race and sex discrimination, of which there are virtually none. But let it also abandon any use of “disparate impact” liability. Disparate impact was initially invoked out of fear that government and private firms would bury their deep-seated racial animus behind pretextual, neutral practices. I doubt this approach was accurate even when the Duke Power Company used certain standardized aptitude tests on promotion cases in the 1960s. The Supreme Court, however, invalidated these tests on dubious statutory grounds in Griggs v. Duke Power.

Nearly forty years later, that suspicious attitude is indefensible when employers both public and private are stumbling over each other in an effort to put affirmative action programs in place. Unfortunately, the perverse decision of Justice Brennan in Teal v. Connecticut allowed the plaintiff to bring a disparate-impact claim even though Connecticut had introduced an aggressive affirmative action program. What covert abuses was he trying to smoke out?

Civil rights suits are not without real social costs, both symbolic and economic. They create the false impression that government agencies harbor deep-seated racial antipathies, which could easily keep African-American applicants from seeking positions with them. Owing to the inescapable frequency of these differences, virtually every test or practice with predictive value could be struck down under the Civil Rights Act. What is needed is a real change in direction. The DOJ should defend affirmative action programs but jettison all reliance on disparate-impact employment suits.

So just what is left for the revitalized Civil Rights Division to do? The division should target state and local governments that, free of any competitive market pressures, pose genuine risks of unchecked discrimination. (A quick read of William Finnegan’s “Profile: Sheriff Joe [Arpaio]” in the July 20, 2009, issue of the New Yorker certainly counts in my book as probable cause for a DOJ investigation.) Remember, on race relations the libertarian insight still holds true. Race discrimination does not survive in competitive markets. But it does flourish when public officials exercise monopoly power without external supervision.