- History

- Military

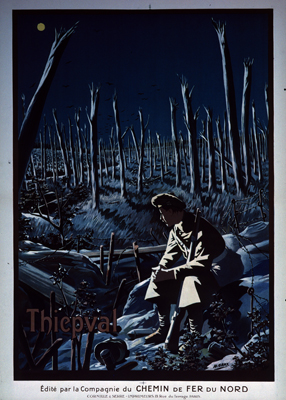

One hundred years ago, on July 1, 1916, five French divisions and eleven British divisions attacked across no man’s land in an attempt to puncture the German lines in northern France. The infantry assault had been preceded by an intense bombardment lasting seven days and involving a thousand artillery pieces. “Nothing could exist at the conclusion of the bombardment in the area covered by it,” said General Sir Henry Rawlinson, commander of the British Fourth Army. He was wrong. Rawlinson and other Allied commanders did not reckon with the ability of the German army to burrow into the ground to withstand the rain of high explosives.

Seeing the defenseless Allied troops walking between the trench lines, the Germans unleashed a devastating salvo of rifle, artillery, and machine gun fire. Nearly 20,000 British troops were killed on the first day of what became known as the Battle of the Somme. It remains the single deadliest day in the entire history of the British army.

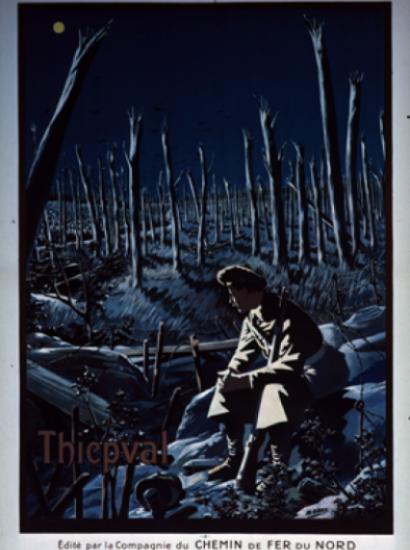

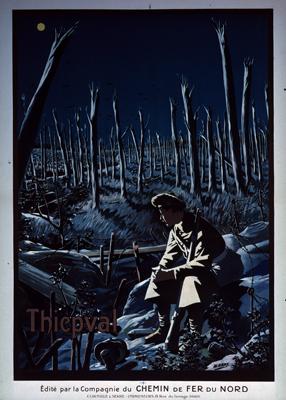

Anyone who visits the British war memorial at Thiepval, designed by Sir Frederick Luytens and built between 1928 and 1932, cannot help but be awed by the scale of sacrifice. Luytens’ arch bears the names of 72,000 officers and men who died in the Somme sector in the succeeding months and who have no known grave. Almost all of them fell between July and November 1916 while the Battle of the Somme raged. In all, more than 310,000 soldiers were killed on both sides of this epic battle. Another 700,000 or so were wounded, many severely.

It is hard, from our 21st-century viewpoint, to comprehend why so many fell. The stakes in the conflict seem far less pressing than in World War II—quasi-democratic Wilhelmine Germany was not the same thing as Nazi Germany. And the methods employed appear to be unimaginably brutish: How could the Allied generals have imagined that an infantry assault into the teeth of enemy defenses could possibly have any result other than a useless slaughter?

It takes an act of considerable willpower to see the situation as the combatants saw it. To the ordinary British Tommies, the war was being fought for the freedom of Belgium, France, Britain—all of Europe—against the threat of “Hun” militarism. While tales of German atrocities may have been exaggerated, they were not concocted out of whole cloth. Kaiser Wilhelm II was no Adolf Hitler—who was?—but Europe would have suffered if he had become its overlord.

As for the way the war was fought: There was no way to do an end-run around the line of fortifications that extended from the English Channel to the Swiss border. The dreams of Winston Churchill and others to strike through the “soft underbelly” of the Central Powers in the Balkans were, in all likelihood, romantic balderdash. In any case, those designs came to grief at Gallipoli. The only way to win the war, and thus end the killing, Allied commanders believed, was to break through the German fortifications.

In this assumption they were not wrong—that is how the war ended in 1918 with the German lines finally buckling under an assault that now included fresh American troops. The end of the war in November 1918 would not have occurred were it not for the terrible attrition that the German forces had suffered during the previous four years. (The British naval blockade also played an important role in weakening Germany.) In that sense, the Allied sacrifice at the Somme was not quite as senseless as it seemed.

But that is scant consolation to all those who fell and to all those who were left behind to grapple with their grief. In 1919 the British poet Charlotte Mew wrote: “Not yet will those measureless fields be green again/Where only yesterday the wild sweet blood of wonderful youth was shed.” Today, the fields where the Battle of the Somme was fought are green again, but they still bear the ugly scars of the second-most-costly conflict in history.