- International Affairs

- World

- Contemporary

- US Foreign Policy

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

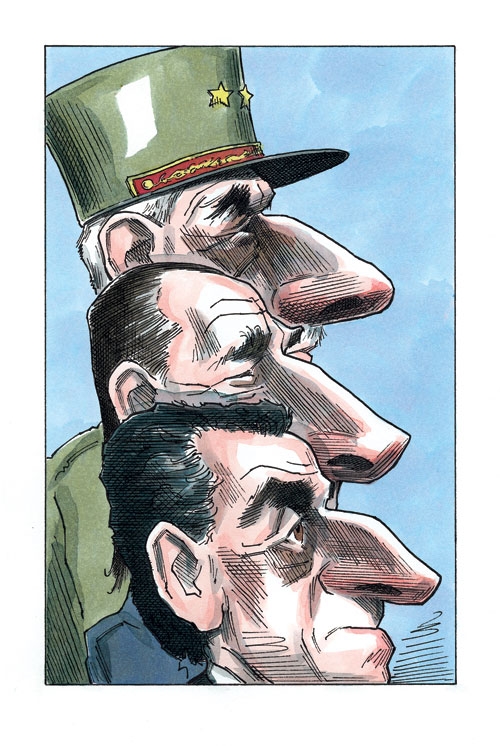

Nicolas Sarkozy’s first year as president of France has been notable—whether facing down public sector unions over pension reform, divorcing his second wife and honeymooning with his third, a former supermodel, or rolling out the red carpet for a high-profile state visit by Libyan leader Muammar Gadhafi. Sarkozy, dubbed l’hyperprésident (the hyperactive president) for his frenetic pace and tendency to micromanage everything and everyone, has kept himself in the limelight. U.S. journalists and political pundits once predicted that a new era in U.S.-French relations would emerge from the so-called Sarkozy revolution. But although he has improved the tone of the U.S.- France relationship, he has not transformed it.

Sarkozy still must operate within the confines of the largely anti-American French political establishment, and he has had to remain internally focused. His most important political priorities are France’s domestic problems— a moribund economy, high budget deficits and national debt, a vocal Socialist opposition, and a restive, unassimilated Muslim immigrant population—and he is trying hard to break with the past to reform France’s economy and business/work environment. On the other hand, he supports continued European integration, and so far his foreign policy agenda is not radically different from his predecessor’s. At most, Sarkozy’s foreign policy goals represent not a revolutionary but an evolutionary change from previous French administrations, and in many ways he resembles the previous French president, Jacques Chirac.

Sarkozy still must operate within the confines of the largely anti-American French political establishment.

Although Sarkozy began his political career as a party activist and has always belonged to the same political party as Chirac, he does not share Chirac’s anti-American Gaullist tendencies, which arise from a political philosophy originating with Charles de Gaulle, France’s president in the late 1950s and 1960s (he was also the provisional president from the fall of 1944 to January 1946). De Gaulle was a fierce believer in France’s destiny as a great power and shared many Europeans’ criticism of U.S. political, economic, and cultural influence in Europe. When de Gaulle regained the presidency in 1958, he overtly campaigned for the restoration of French global influence and European greatness and directly challenged U.S. influence in Europe. Rejecting the bipolar Cold War world, he was an ardent advocate for French independence from both the United States and the Soviet Union. This desire for autonomy ultimately led to French withdrawal from NATO’s integrated military structure because de Gaulle did not want NATO to have ultimate control of French military forces (although France remained a member of the alliance), and to the creation of the French nuclear weapons program.

Chirac shared de Gaulle’s desire for French international greatness; he also overtly challenged American global power and attempted to act autonomously whenever possible. He differed from de Gaulle in supporting the loss of some French sovereignty to supranational EU institutions, but he paralleled de Gaulle in his faith in a strong French-led Europe, able to act independently on the world stage.

FOLLOWING DE GAULLE—TO A POINT

Sarkozy openly admires de Gaulle. He often speaks of France’s need to make a clean break from its past so that it can reform and modernize, following de Gaulle’s example. Sarkozy, as a long-standing member of the French political establishment and product of the French political scene, shares the previous political leaders’ faith in French exceptionalism and destiny for leadership. Sarkozy recognizes, however, that the world has changed, that politics and international relations are different, and that institutions like the EU are here to stay. In particular, he speaks openly about the declining reputation of France in the global arena because of its “arrogance,” as well as the folly of opposing the United States. Because both countries have similar democratic values and systems, he maintains, it is in France’s strategic interest to develop the best possible relations with the United States. Thus, Sarkozy does not advocate developing the European Union as a counterweight to the United States.

Sarkozy has consistently stated that he does not support the use of military force to resolve the Iran crisis. He has referred to “the Iranian bomb or the bombing of Iran” as equally catastrophic.

Sarkozy is a unique French political actor. He did not follow most other politicians’ path into politics, which is to graduate from the National Administration School (ENA) and gain appointment to a position in a ministerial cabinet. Rather, Sarkozy began in 1974 as a grassroots party organizer for the Chirac-led Gaullists and worked his way up, supporting Chirac and the Gaullist parties and then competing for elective office. He has been involved in French politics his entire adult life (more than thirty years), holding elected positions in Parliament and as mayor of Neuilly. His first ministerial job was as minister of the budget in 1993, and he went on to serve as Chirac’s interior minister and finance minister. Sarkozy’s genius has been to capitalize on his family’s Hungarian roots so as to foster his image as an outsider, making it possible for him to criticize French weaknesses and propose sweeping reform at a time when change is desperately needed, and allowing him to align himself more closely with America.

Chirac and Sarkozy have much in common in their stance toward foreign policy. Both have publicly stated their admiration for the United States but insist that friends do not always have to agree. Both have carefully cultivated the image of a France that will not slavishly follow all of Washington’s policies. Sarkozy’s establishing a commission to study the possibility of rejoining NATO’s integrated military structure echoes Chirac’s efforts in 1996–97, as does Sarkozy’s indication that reintegration would depend on France’s being given a significant leadership position in NATO. This French proposal for a “return to NATO” is also predicated on strengthening the European Security and Defense Policy; thus, like Chirac, Sarkozy favors strong European defense.

Despite improved U.S.-French relations, Sarkozy’s government has not reversed France’s position on Iraq. He said in August, “France was and remains hostile to this war.”

Both men also support the concept of a greater Euro-Mediterranean partnership. In October 2007, Sarkozy took Chirac’s policy position a step further during a visit to Morocco, where he called on the Mediterranean countries “to build a Mediterranean Union.” (This ambitious French proposal has been greeted by other EU leaders as tepidly as they greeted Chirac’s Mediterranean vision.) Finally, Sarkozy has continued the policy, begun by Chirac, of working with the United States and the United Nations to eject Syrian influence from Lebanon and support the pro-Western government of Prime Minister Fouad Siniora.

MEETING THE IRAN PROBLEM WITH DIPLOMACY

However, it is the parallels between Chirac’s Iraq policy and Sarkozy’s Iran policy that are most striking. Until the invasion of Iraq in March 2003, Chirac had consistently called for a diplomatic solution to the crisis. The French government repeatedly had emphasized its opposition to the use of military force and said it would countenance a resort to force, sanctioned by the international community, only if U.N. weapons inspections could definitively be shown as a failure. The government also continued to insist, up until the U.S. invasion of Iraq, that inspections were working.

Sarkozy has consistently stated that he does not support the use of military force to resolve the Iran crisis. In February 2007, he stated that he was “absolutely, totally and completely opposed to nuclear weapons for Iran,” but when asked whether he would join Washington in military action, his reply was a flat no. In August, in his first major foreign policy address, he emphasized again his opposition to the idea of a nuclear-armed Iran, calling for a stronger diplomatic push and urging the international community to continue “incrementally increasing sanctions against Tehran while being open to talks if Iran suspended nuclear activities.” Most important, he referred to “the Iranian bomb or the bombing of Iran” as equally catastrophic. Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner’s statement on September 16 that “the world should prepare for the worst, that is, the possibility of a war with Iran, if Tehran persisted in its refusal to suspend its nuclear program” was interpreted by many, including the Iranians, as a French hint that it considered military action an option. But a few days later, Kouchner clarified his comment, saying France does not want war. Prime Minister François Fillon further played down the war rhetoric, stating: “Everything must be done to avoid war. France’s role is to lead the way to a peaceful solution.”

In an interview on September 24, Sarkozy followed up on the issue when he rejected the use of the word “war.” When asked about the U.S. position that “all options are on the table,” referring to the possibility of military force, Sarkozy said, “This expression is not mine. . . . We are not condemned to two extremes. Between submission [to an Iranian nuclear weapon] and war there is a whole range of options.”

The U.S. National Intelligence Estimate on Iran, published in December, has not changed Sarkozy’s position. He still calls Iran a threat (commenting, “Everyone is fully conscious of the fact that there is a will among the Iranian leaders to obtain nuclear weapons”) and continues to insist that the international community must keep up the pressure with strong sanctions. But, like Chirac, Sarkozy prefers to resolve the crisis through diplomacy, multilateralism, and international institutions.

French opposition to the use of military force against Iraq and Iran is based partially on fear of France’s Muslim population. France has the largest Muslim immigrant population in Europe, and French Muslims now number about 6 million. According to the Wall Street Journal, a member of Chirac’s inner circle warned the president that “if he backed the United States over Iraq, he would face nothing short of an ‘insurrection’” by Muslims in France. Given the concern over the persistent exclusion of Franco-Islamic communities from the economic, political, and social life of the state, Sarkozy worries about a violent backlash if another Muslim country were to be attacked.

His position is based on experience. For twenty-five nights, in October and November 2005, riots exploded across France after two Muslim youths of North African descent electrocuted themselves while hiding in an electric power station. Sarkozy, as interior minister, was responsible for national law enforcement and was directly involved in quelling the violence, which was perpetrated primarily by immigrant Muslim youth and spread to 274 towns. Some 10,000 vehicles and 300 buildings and schools were burned, 4,700 people were arrested, and 8,000 police officers and 1,500 police reservists were deployed. Given the volatility of the “Muslim street” in France, no French political leader can ignore the possible domestic reactions to foreign policies.

STRONGER VIEW ON SANCTIONS

French trade relations with Iraq and Iran historically have been extensive, but this is where the Iraq/Iran similarities between Chirac and Sarkozy end: they have taken radically different positions on sanctions and trade.

Before the Iraq invasion, Saddam’s government was in debt to the French government to the tune of $8 billion. French defense sales were in the billions of dollars and French-Iraqi nuclear cooperation was extensive. Moreover, when Chirac was France’s prime minister in the mid-1970s, he signed an agreement with Saddam under which France was to sell Iraq two nuclear reactors. Private sector cooperation in the oil industry was also extensive. France not only undermined the U.N. sanctions regime in the 1990s but also lobbied for its lifting; French government officials were also implicated in the U.N. Oil-for-Food Program scandal.

French trade with Iran is also in the billions of dollars; it peaked in 2004 and has slowly decreased as sanctions have been tightened under two U.N. resolutions, UNSCR 1737 in 2006 (which banned the supply of nuclearrelated materials and technology and froze the assets of individuals and companies related to the enrichment program) and UNSCR 1747 in 2007 (which expanded the freeze and imposed visa restrictions and an embargo on Iranian arms exports). Sarkozy’s position has been surprisingly strong in supporting sanctions. At the September 2007 U.N. General Assembly meeting, he called for tougher U.N. sanctions and later commented that “if the U.N. Security Council were unable to agree on further financial sanctions, the European Union should take its own measures to raise pressure on Iran.” The French government has subsequently called for French divestment from Iran: it has told French companies not to seek new markets in Iran, and in the banking and financial arena, the government has proposed stopping new export credit guarantees. France also began to press its European Union partners, in mid-October at a meeting of EU foreign ministers, to institute tough EU sanctions that would complement and strengthen U.N. sanctions. In particular, France has worked hard to overcome German and Italian resistance, which is crucial because Italy is the biggest European trading partner with Iran, and Germany is by far the largest European exporter to Iran.

Sarkozy openly admires de Gaulle. He often speaks of France’s need to make a clean break from its past so that it can reform and modernize, following de Gaulle’s example.

The lengths Chirac’s government went to in an effort to prevent the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 resulted in a great deal of bad blood between the United States and France. The Iraq disagreement, however, did not prevent France and the United States from subsequently finding common ground in other foreign policy areas—namely, joint cooperation at the United Nations in September 2004 to pass Security Council Resolution 1559, which called for Syria to withdraw its troops from Lebanon.

Despite improved U.S.-French relations, Sarkozy’s government has not reversed France’s position on Iraq. In September 2007, Kouchner called the U.S. intervention in Iraq a failure and commented that he would prefer that the United States establish a timetable for withdrawal. His statements echoed Sarkozy’s August foreign policy speech, in which the president said that “France was and remains hostile to this war.” To date, France has not offered any military support to coalition operations in Iraq.

Sarkozy has, however, taken a significantly different tack from his predecessor on Israel and the Middle East. Chirac was known for his “Arab policies” and his consistently pro-Arab positions, many of which were often detrimental to Israeli interests. Although his stance may not have been anti- Semitic, his overt support for the Palestinians encouraged an anti-Jewish political environment.

In fall 2005, Sarkozy, as interior minister, was directly involved in quelling a paroxysm of violence perpetrated primarily by immigrant Muslim youth—the dreaded “Muslim street.”

But Sarkozy calls the concept of an “Arab policy” nonsense because the Arab and Muslim worlds are not uniform. He supports policies tailored to each region of the world: “We cannot make our relations with Israel conditional on the ups and downs of our interests in Arab societies.” He is also an unapologetic supporter of Israel, maintaining that the tiny democracy has the right and duty to defend itself. Citing the Holocaust, Sarkozy maintains that all democracies must be accountable for Israel’s security; he supports the right of Palestinians to an independent state, but not at the expense of Israel’s existence. Sarkozy’s position on the Israel-Lebanon war in the summer of 2006 was similar to that of the United States: he condemned Hezbollah as the aggressor in the war and defended Israel’s right to self-defense (although he also cautioned Israel to act proportionately). This Middle East foreign policy divergence is potentially significant: if future French positions continue to parallel those of the United States, it will further encourage freedom, democracy, and constitutional government throughout the Middle East.

A FRIEND, NOT A PUSHOVER

Under Sarkozy’s leadership, French-U.S. relations seem unlikely to descend into acrimony, as they did under Chirac. But Sarkozy’s pro-American orientation does not mean that French and U.S. foreign policy positions will always align or that relations will always proceed smoothly. For example, it will be difficult for France to balance strengthening European defense with rejoining NATO’s integrated military structure because, as European defense develops, it will become more autonomous. If France fully rejoins NATO, it will be giving back to NATO (that is, the United States) control over French military forces. The negotiation over a new NATO leadership position for France could also break down. To his credit, Sarkozy is proceeding openly in this area, and the official he appointed to study the issue has already held talks with European partners and representatives of the United States, the European Union, and NATO.

As a protégé of Chirac and an admirer of de Gaulle, Nicolas Sarkozy is unsurprisingly an advocate for a strong and influential France. He talks about the benefits of globalization, foreign trade, and the market economy, but he does not want to import the “Anglo-Saxon” economic model of free market capitalism. He is still a believer in the benefits of state intervention, the welfare state, and the French social model. Although Sarkozy talks constantly of a crisis in confidence in France and of making a clean break, of restructuring, reforming, and modernizing, he insists that the French people “don’t want a radically different France.” U.S. policy makers should not have any illusions about Sarkozy. He does not represent a revolution, but rather a desperately needed evolution.