- History

- Military

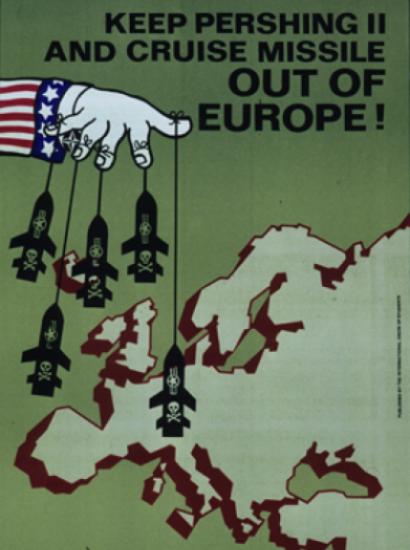

Given the diplomatic and strategic weaknesses that the United States and its leaders have exhibited over the past six years, it is almost inevitable that America’s allies, which exist in substantially more dangerous neighborhoods than does the United States, will seek to develop their own nuclear capabilities. Some may well have embarked on that course already, at least to the extent of designing, fashioning parts, and laying away the nuclear material necessary to construct nuclear weapons. The case for developing and possessing such weapons is more obvious and pressing in the Middle East and the Pacific than it appears to be in Europe. But even in Europe, Russia’s behavior has created the uncertainty necessary to push the Poles and the Germans to think about creating a nuclear deterrent.

For the Germans the existence of a strong Poland, as well as the French and British nuclear arsenals, provides a certain sense of security that makes it doubtful that the Germans would go nuclear. But the Poles are another matter. They face substantially different strategic and geo-political realities. Should the United States continue its drift toward isolationism and removal of its military and strategic presence in Europe, memory of centuries-long mistreatment at the hands of the Russians may well drive the Poles toward creating a nuclear option for their military forces. The fact that the Russian military ended a recent major war game by launching a tactical nuclear weapon at Warsaw can do little to reassure the Poles about President Obama’s announcement about “peace in our time.”

The Middle East presents an even more depressing picture. Over the past half-century, radical regimes committed to revolutionary change in the region have aspired to create their own nuclear capabilities, justified at least to their internal constituencies by Israel’s possession of such weapons. Clearly, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq was heading toward the creation of a nuclear capability until the Gulf War in 1991 wrecked Iraqi pretensions to be a great power and the intense pressure of the subsequent UN inspection routine eliminated the Iraqi program. The potential of Iraqi possession of their own nuclear weapons was particularly dangerous because of the fact that Saddam had every intention of using such weapons in a war with the Israelis. Assad’s Syrians were following the same trajectory until the Israeli raid of 2007 eliminated their facility. That left the Iranian program, which has moved haltingly toward the creation of nuclear weapons, delayed by the cyber attack on their computer systems by either the Israelis or the Americans—or both. At present, the Iranians are close to the creation of nuclear capabilities. How close is a matter of debate, but close enough to cause serious fears throughout the Gulf and in Israel. A continued American withdrawal from the region will undoubtedly push the Saudis toward crossing the nuclear threshold; and while that capability should raise few qualms, the successors to the present rulers are another matter.

At present North Asia is one of the most dangerous areas in the world in spite of its enormous economic successes. The mere presence of a nuclear-armed North Korea, which has displayed considerable powers of survival, provides a rude reminder that peaceful relations are not necessarily at the heart of the strategic policies of the various powers in the region. China already possesses nuclear weapons, which, with its exceedingly aggressive aims and steadily increasing military capabilities, provides a serious threat to regional stability.

The other major players in the region, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan, all have the capability to build serious nuclear capabilities without great difficulties. One might think that the American pivot towards Asia and away from Europe and the Middle East would reassure America’s allies in the region. Unfortunately, the Obama administration has performed its change of America’s strategic focus with all the ineptitude and lack of sophistication of Joachim Ribbentrop’s diplomatic moves, but with little sense of the mailed fist that underlay Nazi moves.

The current Chinese assertion to their claims to the Senkaku Islands underline a strategic policy aimed at returning Asia to the sixteenth century, when China dominated not only Southeast Asia, but East Asia as well. The possibility that oil underlies the Senkaku chain further exacerbates the tension between China and Japan. But the real problem is the fact that centuries of conflict between the Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans mark the region’s historical background. Each power has its own narrative of the past, none of them connected with a serious examination of what really happened in the past. The presence of significant numbers of American troops along with America’s nuclear umbrella has so far dampened down the desire of the Koreans and Japanese to go nuclear. Hiroshima and Nagasaki have added to the Japanese forbearance.

But to a considerable extent, a belief in the efficacy of deterrence rests on perceptions. A feeling among Japanese leaders that they cannot rely on the United States will lead them to create their own nuclear capabilities. The same will hold true for the Koreans, while the Taiwanese probably already possess nuclear weapons. In the end, what will drive the continued stability of East Asia and the willingness of these highly sophisticated powers not to cross the nuclear threshold will be the perception that the United States will stand by its allies. And that perception has slowly ebbed away over the past decade. The wretched picture American leaders—not to mention the Europeans—have made over Russian actions against the Ukraine has only exacerbated perceptions of America’s decline.