- Economics

- International Affairs

- World

- US

- Contemporary

- Economic

- US Foreign Policy

- History

In our dealings with Russia, it is essential to know exactly who and what we’re dealing with, instead of working under the romantic view that there are a hundred million democrats in Russia waiting for the Putin regime to fail so they can create a Jeffersonian democracy. Vladimir Putin and his companions, however, are attempting to articulate and consolidate a new Russian political identity. Although words such as autocratic and imperialistic are often used to describe Putin’s Russia, the new leaders’ goal is not simply to enhance and stabilize their own and Russia’s state power; those easy characterizations ignore the distance Putin has created from Russia’s communist past even as he openly defies the West.

When you create a new identity in the absence of institutions, personality becomes especially important. A cult of personality has arisen around Putin, and its function is to make clear to those both outside and inside Russia that there’s a new name in town—and it’s not democracy and it’s not Yeltsin.

Putin is very different from Boris Yeltsin. Putin is cold, aloof, impersonal, ruthless, and pragmatic, with his personal stature in Russian politics making concrete the Russian state’s new identity. As Thucydides noted about Pericles, “What was nominally a democracy became, in his hands, government by the first citizen.” Putin dominates Russian politics even though he voluntarily gave up the presidency for the lesser position of prime minister.

Putin’s deliberately rude language—verbal and body—distances him from the polite norms of most international dialogue; from ordinary politics in Russia (he has not joined the very party that he leads, United Russia); and, most crudely, from the role of ordinary politician.

For Putin and his companions, reality consists purely of interests, state interests: What’s the deal? Who wins? Who loses? Here Putin’s idiom is pure Thrasymachus, who told Socrates that “justice is nothing else than the interest of the stronger.” In Putin’s view, world politics resembles judo, his favorite sport, of which he has said, “It’s not for weaklings.”

High Anxiety

Russia’s international defiance is manifested by its refusal to join the European Union or NATO. From Putin’s perspective, joining either entity would make Russia into a post–Cold War “West Germany,” a stateless, merchant entity with no national identity. Russia also manifests defiance in its talks with Cuba and Venezuela about naval bases, as well as with China about the formation of the Eurasian Economic Council and the Shanghai Cooperation Group.

The stimulus for Putin’s efforts to distance and differentiate Russia from the West, and defy it, to make concrete its new identity, is the anxiety typical of any weak entity trying to set itself in opposition to more powerful existing ones.

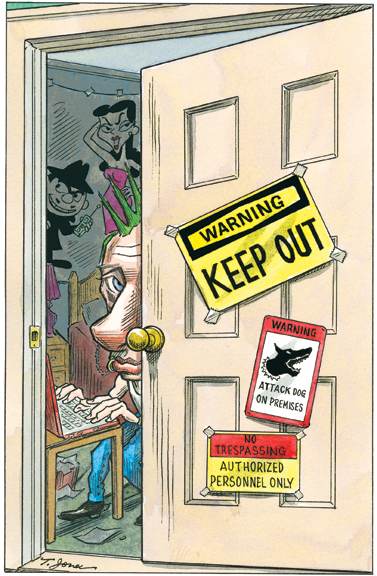

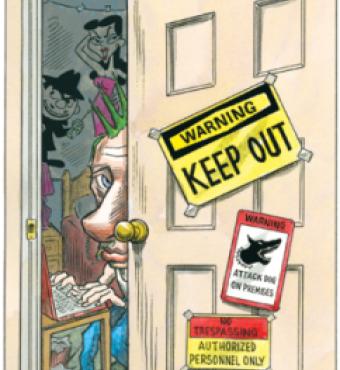

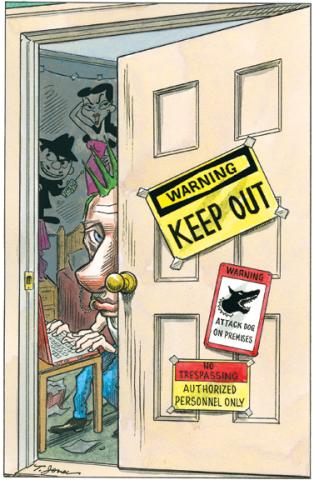

The Putin elite is in its “junior high school” phase. At the time when young American teenagers enter junior high school, remarkable things happen. The door to their room—formerly open and parent-friendly (in Russia’s case, to its “Western parents”)—is now closed and often plastered with rude instructions to stay out. Inside the room is a barely recognizable person whose hair color, music, and language have become odd and whose demeanor and behavior are increasingly sullen, rude, and even combative. If the relationship of the Yeltsin elite to the West was a preadult identity, blurred and entangled with the “parents,” the Putin elite is going through a deliberately hostile process of teenage identity definition and differentiation.

Wearing black leather jackets to rock concerts, hurling despicable insults at the United States, claiming that in many ways we have been worse than the Nazis and Stalin—these actions are Putin’s effort to gain Western attention in the pursuit of Russian separation, a demand that growing differences be recognized and accepted.

The Putin elite and the American teenager both embody a newfound sense of power combined with continuing weakness: for the teenager, the need to live at home and accept financial support; for Russia, dependence on a global capitalist system and a strictly limited international space within which to exercise power and influence.

Initially, anxiety was the response to the often-indiscriminate tendency of the Yeltsin elite to mimic the West. Although the degree of anxiety varies, from the relatively confident President Dmitry Medvedev to the anxious Putin to his hysterical adviser Gleb Pavlovsky, the entire Putin elite shares a high sense of anxiety in response to

- The flood of American democracy and market advisers in the 1990s, which it perceived as an ideological neocolonial effort;

- The color revolutions, orange (Ukraine) and rose (Georgia), which the Putin elite saw as American red, white, and blue;

- Globalization, the presumably benign, homogenizing global force that would replace the Cold War.

Putin and his companions cast these developments as insidious, powerful, penetrating, and contaminating forces, and they have responded with deliberate efforts to create barricades in place of porous boundaries, to create the conditions and space for the emergence of a state-mercantilist Russia.

Imperialist or Mercantilist Identity?

Since the Soviet Union’s collapse there is only one globally powerful, defining modern ideology: Western liberal democratic capitalism. Today, there is no critical social, political, or philosophical mass in Russia to support a liberal democratic-capitalist reality. Given the obstacles to a practical Western ideology’s emerging in contemporary Russia, and the dangers of a rage-filled anti-Western one emerging should Putin fail, I see the emerging features of a state-mercantilist Russia led by Putin and his allies.

The term autocracy is routinely (and lazily) applied to any nondemocratic person or government these days; used in reference to Russia and Putin the meaning is clear: not being a Western democracy, Russia must be an autocracy and Putin an autocrat. In fact, the Russian polity is authoritarian— it is stronger than under Yeltsin but still rather weak in all but a nuclear sense. There are very real limits to Putin’s power: he does not have Stalin’s “sultanist” autocratic power. I doubt he wants it.

It is one thing, by no means insignificant, to resurrect Stalin symbolically on television and in the classroom; it is quite another to want a return to class war inside Russia and “socialism in one country.” Putin wants neither. He has pointedly said that the time for revolutions in Russia is over and that Russia must be in and of the larger world in order to develop. Putin sees Russia as a great state with sovereign power that will defend its sovereignty, be treated as equal by other great powers, and exert influence commensurate with that power.

That means that although Russia is objectively weaker than the United States, it will now set limits to the United States’ ability to consider the world, particularly that part of it geographically proximate to Russia, as missionary territory to be freely occupied by American entrepreneurs, political proselytizers, or military outposts.

On a global scale it means that Russia, along with China and soon India, will demand that its global economic weight and interests be recognized, as well as its military stature. The interests of those nations might coincide, be competitive, or possibly be hostile to one another and to the United States or the European Union, but they must be recognized as legitimate if violence is to be avoided.

None of this qualifies as imperialist; all of it is perfectly compatible with state mercantilism. For this discussion, these features of state mercantilism are state centralization at the expense of regional fragmentation and universalism, economic development leading to state and global power, and the preferred substitution of economic for military rivalry. Obviously, a doctrine such as state mercantilism that favors the state over civic or ethnic power has an affinity for accumulating military power along with economic might. That certainly applies to Russia today.

It’s necessary to stress, however, that mercantilist states prefer acquisition to aggression, powerful economic institutions to military ones. Putin has explicitly noted the mistakes of the Soviet Union in this regard.

Last year, for instance, Russia could have occupied all of Georgia after its August incursion. Russia could also bring Ukraine to its knees at any time but has no desire to do so. The chaos that would follow in Ukraine and Georgia would interfere with Russia’s need to maintain domestic economic and political stability. In addition, Russia’s economic interests and relations with the European Union would be severely damaged. Russia’s state doctrine is neither that of an ideological missionary nor that of an aggressive warrior. It is not fascist. It is not Leninist. It is mercantilist.

Living with Second Best

The threat to Russian stability today is not military. No one is going to invade Russia any time soon, and no one is going to direct a nuclear attack against it. The threat is internal, arising from the existence within the Putin elite of people such as Pavlovsky, with their hysteria about “hidden Western enemies” threatening to dilute and pervert Russia’s identity. At present they are more influential than powerful.

Should the Russian economy collapse, however, or countries such as Ukraine and Georgia be admitted to NATO or even if missiles are placed in Eastern Europe, then one might see a new Russian polity emerge that is more nihilist than imperialist—never mind democratic.

In light of the economic recession and what Russia is today and what it is not, a state-mercantilist Russia led by a nonideological Putin may not be the optimal political outcome. But in 2009, it’s not a bad second best.