- Budget & Spending

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Economics

In his State of the Union message in January, President

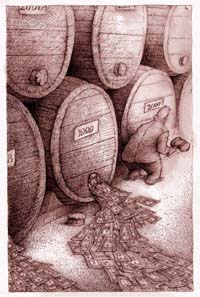

Clinton called for using “every dime” of the budget surplus to help ensure Social Security’s future. “Save Social Security first!” was his simple prescription for how to use the money. His budget, however, contains a different message: “Spend it!” The president’s budget proposals would, over the long term, divert the surplus to other government programs. Future Social Security recipients—and the public at large—would be better off if Congress simply ignored the president’s budget.

President Clinton’s budget predicts that without any changes in taxes, and if Congress continues to live within the spending limits that it previously agreed to, the economy will create a budget surplus next year. The amount of the surplus is projected to rise each year thereafter, reaching nearly $90 billion in 2003.

The president, though, is proposing a raft of additional spending programs and higher taxes to pay for them. Initially, the new spending is less than the new taxes. But after 2001, when the full impact of the president’s proposals will be realized, the new spending would exceed the added revenue.

The president’s proposals would raise federal taxes to more than 20 percent of gross domestic product, the highest federal tax burden since World War II.

Financing the shortfall would require a future president to draw from the surplus—the one that President Clinton has pledged for Social Security. Even the president’s budget predicts that more and more of the surplus would be siphoned off for these programs. By 2003, the last year for which his budget provides estimates, the amount would reach $7 billion.

The Clinton administration’s defenders might counter that the diversion is relatively small. But that misses the fundamental point: The administration’s proposals would lead the country in the wrong direction.

There are several schools of thought on how Social Security might be salvaged—building a surplus in the program, privatizing it, or increasing economic growth. But the president’s idea—pledging the surplus to the task but then later taking it away—is unique.

Also, history shows that both Republicans and Democrats tend to underestimate the cost of new programs and overstate the revenue from tax increases. Thus those small diversions the president is projecting for a few years hence to pay for his 1999 initiatives will probably loom large by 2012, when the first baby boomers retire.

Two years ago, the president firmly stated that the era of “big government” was over. Now, he has reversed himself. The president’s legislative proposals call for greater increases in federal spending relative to current law than did the legislative proposals in any of his previous five budgets. He proposes a larger federal role in education and child care, a larger Medicare program (by lowering the age of eligibility), and more money for fixing roads and bridges. His initiatives would cost more than $120 billion over the next five years. To permit this higher level of spending, he breaks the budget rules that have contributed to fiscal discipline since 1990.

In each of his earlier budgets, the president proposed to offset most of his spending initiatives with cuts in the growth of other programs. His current budget makes no such pretense. Instead, he relies on more revenue from a growing economy and on higher taxes.

His budget projects that economic growth will generate some $200 billion more a year for the next five years. President Clinton also proposes new taxes that would generate another $100 billion over five years. Two-thirds of that would come from taxes on cigarettes. The rest would come from fees on boat owners, banks, fisheries, airlines, visitors to national parks, home health care agencies and physicians, even dog kennels and chicken farmers. His proposals would raise federal taxes to more than 20 percent of gross domestic product, the heaviest federal tax burden since World War II.

A budget that proposes to tap the surplus of the future to finance higher government spending today is a terribly misguided one. Clearly, a “tax and spend” budget is also misguided. A larger federal government is not what we need. Congress should reject the president’s budget and, unless it can do better than current law, let last year’s budget agreement stand and adjourn.