Security Council Resolution 1701, adopted unanimously on August 12, contains the bases on which a lasting peace could be established along the Lebanon/Israel border and true sovereign authority transferred to Lebanon’s government. But these objectives will succeed only if the resolution’s demands are met. And although the new resolution has elements that make it stronger in some ways than its predecessor, Resolution 1559, those new elements—and Israel’s effort to weaken Hezbollah—are unlikely in themselves to bring about a different outcome. Successful implementation depends on convincing Syria to end its policy of allowing Hezbollah to be used by Iran to destabilize Israel’s security.

Resolution 1701 calls for Israel to withdraw from Lebanon only as the Lebanese Army and an expanded United Nations force assume control. It calls on Lebanon and Israel to support a “permanent cease-fire and a long-term solution” based on full respect for the Blue Line border between Israel and Lebanon; an arms-free zone south of the Litani River; Hezbollah’s disarmament; and an end to the importation of weapons. These outcomes, however, all depend on the Lebanese government’s determination and capacity.

The U.N. force is authorized only to assist the Lebanese government. It has no authority to act on its own in enforcing the resolution’s demands, although it has recently been given reasonably robust rules of engagement. Furthermore, although Hezbollah said it would comply with Resolution 1701, Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah has already used language in the resolution to link Hezbollah’s obligation to disarm with the solution of both the Shebaa Farms and the Lebanese prisoner issues. Regarding the former, 1701 (although confirming the border agreed to by Israel and the Lebanese government) calls on the secretary-general to develop proposals for delineating the international borders of Lebanon, especially in those areas where the border is disputed or uncertain, including the Shebaa Farms area. On prisoners, the resolution encourages the efforts aimed at urgently settling the issue of Lebanese prisoners detained in Israel. The Shebaa Farms and prisoner issues, after all, were the principal bases on which Hezbollah carried out its attack and abducted Israeli soldiers.

| If victory over Hezbollah can best be ensured by turning Damascus away from its current policies, then we should be persuading Damascus to do just that. |

The resolution may also limit Israel’s capacity to defend itself. The U.N. force will have greater authority than it has had in the past to use force “to ensure that its area of operations is not utilized for hostile activities of any kind.” But it will also have authority to use force “to protect civilians under imminent threat of physical violence.” This obligation is not qualified to allow Israel to act in its reasonable self-defense. Hezbollah will be able again to infiltrate the communities in southern Lebanon and use residents as shields in attacking Israel. The U.N. force is likely to regard itself as required to stop Israel from harming those civilians. Moreover, 30,000 troops is a larger number than were in southern Lebanon before the new resolution but a small force to control 900 square kilometers.

Dealing with Damascus

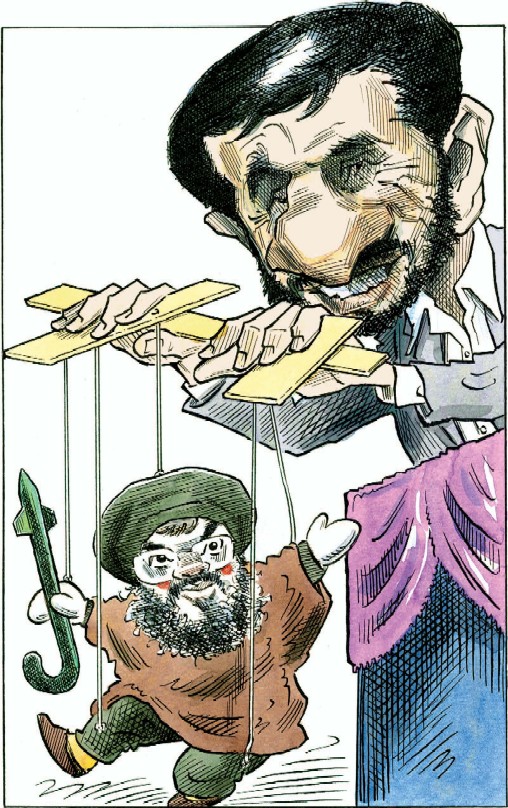

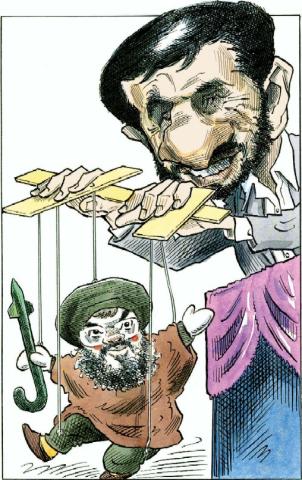

The underlying problem that must be addressed to create stability in the area is the fact that the Lebanese government has been incapable of controlling Hezbollah, which has been armed by Iran with Syria’s cooperation. It is difficult to believe that the Lebanese government will now be able to control Hezbollah without Hezbollah’s acquiescence, which is likely to depend, not so much on what Lebanon, Israel, and the U.N. Interim Force in Lebanon do, but on whether Syria supports the changes.

| Successful implementation of U.N. Resolution 1701 depends on convincing Syria to stop permitting Iran to use Hezbollah to destabilize Israel. |

Resolution 1701 pointedly calls on all states to “take the necessary mea-sures to prevent” the supply by their nationals or from their territories of all forms of military equipment and training to any entity or individual in Lebanon, other than to the government of Lebanon or to the U.N. force. Iran and Syria will violate this provision if they continue supplying and supporting Hezbollah. But the resolution does not authorize any sanction for violating this provision, and Syria and Iran have already violated with impunity a similar resolution adopted after the attacks of 9/11.

Condoleezza Rice put it well when she noted that it was her “turn” to negotiate a peace between Israel and one of its neighbors. She has done well so far in putting in place a resolution that contains sound principles on the basic issues. She must now proceed with the part of the process on which future stability depends: determining how to get Syria to end its policy of using Hezbollah to create instability. This will be a two-way process in which she must tell Damascus what Washington wants and also listen to what Damascus wants—though not necessarily give it what it seeks. She must engage Syria to warn it of the consequences of continuing a policy that must someday soon be forced to end (not only in Lebanon but in Gaza and Iraq as well), and to offer assistance in securing legitimate ends.

To that end, Rice might consider Henry Kissinger’s reaction to Anwar Sadat’s attack on Israel in 1973. Egypt would have destroyed Israel then if it could have. But Sadat’s aim was to get back all Egyptian territory lost in the 1967 war. Rather than condemning Sadat for invading Sinai, Kissinger acknowledged that the United States had paid too little attention to Israel’s occupation of Egyptian territory and that Sadat had “got our attention.” He secured a cease-fire and then brought about a series of disengagements by Israel, with reciprocal commitments by Egypt, laying the groundwork for the Camp David talks and the treaty that has now held for almost 30 years.

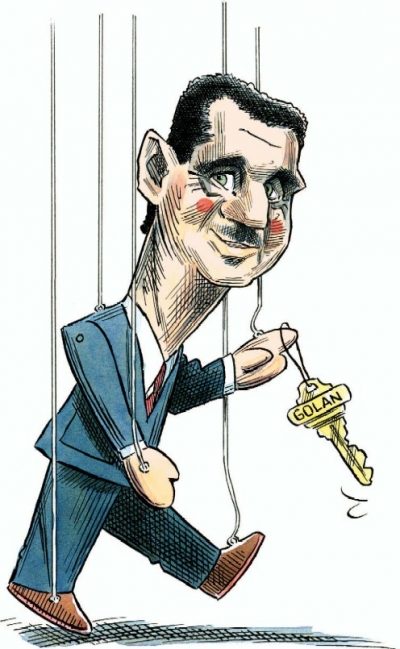

Rice will not secure Syria’s cooperation by simply asserting that Damascus “knows what it has to do.” Indeed, Damascus has done what it believes it has had to do to get the attention it seeks. And it will presumably continue to do this until Israel withdraws from the territory Syria lost in 1967. Israel has legitimate concerns in surrendering the Golan Heights, but they are not insurmountable and do not justify a stance that in effect tells Syria that it will never regain sovereign control.

Territory for Peace

Despite the difficulties involved, the key objective of Israel and its allies, as well as of any state or group interested in securing progress in the Middle East, is to make it possible for Israel to withdraw from non-Israeli territory without causing increased insecurity and danger for its people. Although some of Israel’s supporters speak of destroying and subjugating its enemies, the Israeli people know better than to pursue so futile a policy, and have shown a willingness to return territory for peace. Treaties now exist between Israel and both Egypt and Jordan.

| The U.N. force is authorized only to assist the Lebanese government. It has no authority to act on its own. |

When it became clear to then–prime minister Ariel Sharon that the Palestinians were determined to make war on Israel, he established the policy of withdrawing from Gaza and building a fence to separate Israelis from Palestinian areas. He did not expect peace because of disengagement; he disengaged because he concluded that peace was unobtainable and that separation was a more effective way to fight. The Olmert government was elected to continue the process of disengagement begun by Sharon; its ability to do so will depend on the international community’s understanding its need to suppress the attacks that continue from Gaza.

Resolutions 242 and 338, which establish the principle of territory for peace, are cited in the final operative paragraph of 1701 as the ultimate objective for “a comprehensive, just and lasting peace.” That principle applies as much to Syrian territory as it does to Lebanese or Egyptian territory. As uncomfortable as it may be to recognize, Syria must be given our attention. Fighting Hezbollah is indeed part of the war on terror that must be fought and won. But if victory over Hezbollah can best be ensured by turning Damascus away from its current policies (along with an end to Syrian support for terror in Gaza and Iraq), then that is what we should try to do, conveying both a willingness to deal with Damascus fairly, as well as a determination to hold it accountable for failing to comply with Resolution 1701’s demands.