- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

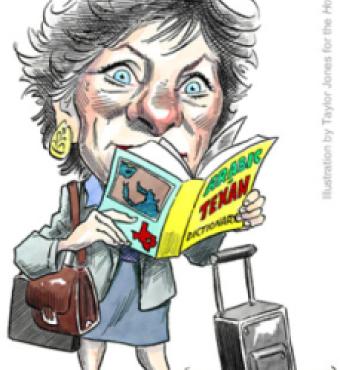

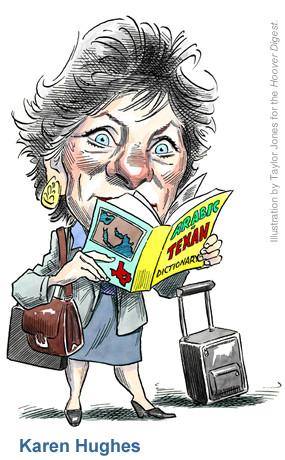

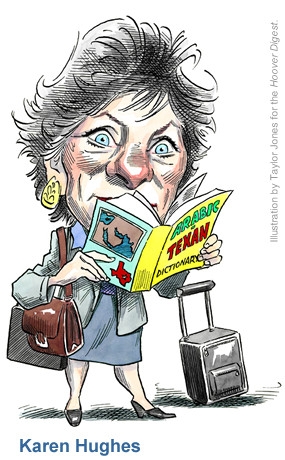

It’s not every day that the government is presented with an opportunity to educate the nation, fortify national security, and enhance public diplomacy, and to do so with a simple program that can be administered with a tiny staff and implemented at bargain prices. Yet the establishment of a program to fund scholarships for undergraduates and graduate students to study foreign languages, particularly Arabic, represents just such an opportunity. And Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy Karen Hughes, who recently returned from the Middle East where she had been conducting a “listening tour” among Arabs, is in an excellent position to seize the initiative.

Of course, Ambassador Hughes’s principal task, as the president noted at her swearing-in ceremony last September, is to explain to the world U.S. aims and principles. And she will certainly have her hands full with this large and neglected responsibility. But the president also emphasized that he wanted Hughes in discharging her duties to work with Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice “to encourage Americans to learn about the languages and cultures of the broader Middle East.”

This endeavor, the president pointed out, will not be novel: “In the early days of the Cold War, our government undertook an intensive effort to encourage young Americans to study Russian language and history and culture so we could better understand the aspirations of the Russian people and the psychology of those who oppressed them.” And his secretary of state, the president also observed with pleasure, is a beneficiary of that Cold War initiative, who displays its wisdom every time she converses with Russian diplomats in their native tongue.

Yet one year into Rice’s stewardship of the State Department and more than four years into the global war on terror, no plan has been announced by the Bush administration to encourage the study of Arabic, Turkish, or Persian at U.S. universities.

From a national security point of view, however, there is no time to waste. According to the 9/11 Commission report, in 2002 U.S. colleges and universities granted a sum total of six undergraduate degrees in Arabic. The report also found that the government has too few translators and that those it does employ lack, in many cases, the requisite proficiency in Arabic. This deficiency impairs intelligence collection and analysis, hobbles the rebuilding of Iraq, and threatens overall U.S. efforts to promote democracy in the broader Middle East.

Secretary of State Rice’s experience, not only as a student recipient of government-sponsored foreign-language fellowships but as a Stanford provost and a professor of political science, makes her uniquely qualified to make the argument for, and oversee with the assistance of Ambassador Hughes, the crafting of a new program of foreign-language fellowships to help America meet the challenges of a new century.

A new program—National Foreign Language Fellowships—would involve a small office and a lean budget. A few officials reviewing applications for study of Arabic, Turkish, and Persian, and a few million dollars worth of fellowship support—a drop in the bucket for the national budget—could go a long way toward meeting U.S. needs. If it wished, the administration could easily expand the purview of the program to cover Chinese and Hindi without a significant increase in staff or budget.

Such a program is more immune than most to politicization. To be sure, any topic can be abused, but the acquisition of vocabulary, the conjugation of verbs, and the mastery of cases and tenses provide many fewer opportunities than, say, courses on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Such a program prepares students not only for careers in government but also for careers in business, law, medicine, and the nonprofit sector as U.S. interests become increasingly bound up with a peaceful, prosperous, and democratic Middle East.

Such a program is entirely consistent with the highest ideals of liberal arts education in America. Indeed, the decline of serious study of foreign languages at American universities, and the ignorance of other peoples and the diversity of nations that it permits, is an academic scandal.

And such a program will make Karen Hughes’s new job easier. For when she, the hundreds of State Department officials who work under her, and U.S. ambassadors around the world undertake to explain U.S. aims and principles to citizens of other countries, they will be able to point to this country’s generous and enthusiastic funding of foreign-language study as an illustration of America’s democratic commitment to understand better the peoples and nations with which it shares the planet.