- History

In the immediate wake of the Brexit vote, a normally astute talk-show host declared, gleefully, that “the European Union is dead.”

One begged, and begs still, to differ. The EU is a bureaucratic monster that interferes absurdly with “the structures of everyday life.” Its grand rhetoric masks expensive inefficiencies and military powerlessness: In global affairs, it’s a chatroom. On the economic side, its attempt to establish a common currency, the Euro, was folly, unleashing some economies but debilitating others. It’s unable, without NATO, to defend its borders, and its non-response to mass immigration has been cowardly, immoral, and self-destructive.

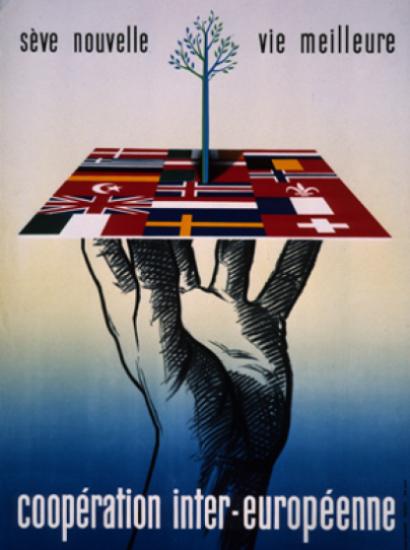

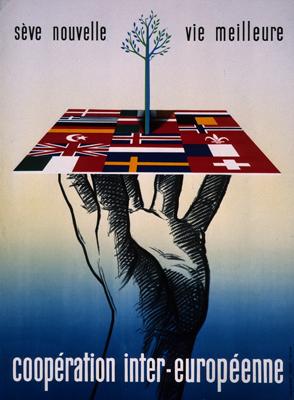

And for all that, the EU remains a miracle to cherish, an experiment that has changed world history for the better. It’s the guarantor of peace among yesteryear’s masters of destruction, and it has provided far-better lives for hundreds of millions within its boundaries. The EU’s failures make headlines, while its breathtaking long-term triumph goes unappreciated.

While gains in Europe’s prosperity have been remarkable (if cyclical), the greatest contribution of the EU has been to make war all but impossible between constituent populations who slaughtered each other for centuries over minor border adjustments, dynastic spats, ethnic delusions, greed and, of course, God. Nations that within the lifetimes of men and women still living among us enthusiastically engaged in the greatest wartime butchery in history now squabble, disarmed, about farm subsidies, fishing rights, and bail-outs. Countless minor resentments remain, but as the recent landslide win of a pro-EU French presidential candidate underscored, even malcontents vote to keep the EU payments coming.

The EU has been the most successful bribery operation in history: Allotments replaced armaments; consumption replaced conquest. (In an unintentional irony, this peaceable behemoth chose Charlemagne, the sword-in-hand unifier of post-Classical Europe, as its symbolic figurehead—ignoring the awkward fact that, during the 46-year reign of that semi-literate conqueror, Europe only saw peace for a single year.)

The EU we think we know today was born in 1951 as the European Coal and Steel Community, a European initiative to enmesh a recovering Germany in a western-European economic net of six key countries. This quickly evolved into the European Economic Community, a more-ambitious effort at integration. From that we saw the rise of a political and regulatory bureaucracy, today’s EU, codified by the 1993 Maastricht Treaty.

At every step, there were naysayers, and at every step they were wrong. Today, the EU has 28 member states (with the United Kingdom emotionally divorced but still living in the house). And it has abundant problems. Yet, given the profound cultural, historical, and economic differences between its members, the sturdiness and appeal of the EU remain remarkable.

If any strategic mistake has been made, it’s been the creation of a common currency, the Euro, adopted by 19 of the EU states. A great convenience for tourists, the Euro has been devastating for southern-tier economies—it was folly to imagine that a single monetary policy could be made to fit Germany and Greece, the Netherlands and Italy. Yet, despite the economic crises in Europe’s south in recent years, the hullaballoo about states such as Greece, Spain, or even Italy leaving has come to nothing. The only state that moved to secede has been the UK, with its resolute eccentricity and powerful financial services sector (thanks, not least, to EU membership). And even in the UK, recent elections revealed quitter’s remorse on the part of voters.

As for Brexit, it did not herald a collapse of the entire EU, but served as a useful stimulus to reform. The Brussels bureaucracy had grown even more swiftly in power and size than had the EU overall. And the bureaucrats, constantly seeking self-justification, had overreached to extremes of regulatory silliness. Brexit has forced the EU to sober up, not break up.

The EU may, indeed, lose some peripheral members over the years. Despite its position as the second most powerful reserve currency (behind the US dollar), the Euro ill serves Europe’s south—making northern European exports more competitive, while driving up internal and export costs south of the Alps and Pyrenees (on top of which European Central Bank regulations punish Italians, Greeks, and Spaniards for not being Germans).

Yet, the EU will be with us for decades—many decades, one hopes—to come. Expensive, addled, intrusive, self-righteous, and often unfair, it’s nonetheless the unexpectedly pacific, even noble, outcome of centuries of political evolution that, until 1945, had drenched the continent with blood.

To truly grasp the value of the EU, as well as to identify its parentage, we have to reach back at least to the late 18th century, when the rationality-extolling Enlightenment collapsed into the inchoate passions of the Romantic era and the decaying monarchical system excited revolution and unleashed the newborn demon of nationalism.

We forget that, as Bonaparte plunged into Italy in 1796, not all French citoyens thought they were French. Italy was a hodgepodge of senile kingdoms, stagnant dukedoms, one false republic and the Papal States. Germany was even more of a patchwork than the Italian peninsula and its dependent isles. Ruled from Vienna, the polyglot Habsburg Empire was glued together by internal force and external fears, and the Balkans remained largely possessions of the degenerate and brutal Ottoman Empire (today, the EU states that fiercely resist accepting “their share” of Muslim immigrants are those whose national memory recalls centuries of Ottoman occupation).

The explosion—sometimes quite literal—of nationalist sentiment between the Napoleonic era and the formal unifications of Italy (1870) and Germany (1871) changed the European landscape profoundly. Populations accustomed to local allegiances and who expressed themselves in exclusive regional dialects (in 1870, fewer than ten percent of “Italians” made common use of Italian as we know it) discovered, or imagined, bonds of blood, history, culture, and language. From the novels of Manzoni to the operas of Wagner, poets, pamphleteers, politicians, artists, and even musicians romanticized an often-mythic national past. And virile, virulent nation-states coalesced in the wake of wars and revolutions. (Artists and philosophers made Hitler inevitable, but that’s another tale for Leftists to ponder.)

Those exuberant nation-states, along with peculiar, self-immolating Russia, then embarked on the horrific wars that stretched from 1914 to 1945, gutting the continent and leaving its eastern half enslaved by a perverse German ideology, Marxism, further debased by its maturation in Moscow.

The year 1945 marked the crash (though not the complete disappearance, of course) of nationalism, which has been followed by a paradox: “Blood and iron” nationalism has been discredited, and cobbled-together statehood questioned. Within states, the trend is toward the devolution of power, even secession, as Flemings and Walloons debate the worth of a unified Belgium; Lombards and other northern Italians ask why they should bear the fiscal burden of the Mezzogiorno; Basques and Catalans wish to shrug off the rest of Spain; and—as an object lesson—Yugoslavia (which was not part of the EU) broke apart amid massacres in the 1990s, as Orthodox Christians, Roman Catholics, and Muslims remembered that they hated each other.

Yet, neither Catalans nor Basques, Lombards or Walloons, want to leave the EU. Indeed, defeated Scottish nationalists view Brexit as a lifeline for their cause—many Scots, if not a majority, would prefer to remain in Europe.

So…we have a crumbling of the weaker national identities, but a general allegiance to the overarching EU super-state, for all its practical faults. Although it does not do to exaggerate its strength, there is a European identity now that never before existed, not even when Christendom was most imperiled by Muslim invasions that reached central France or Vienna.

In yet another irony, the Islamist terrorists plaguing Europe and the flood of Muslim immigrants further foster a European identity, a shared sense of us-against-them. Europeans disagree profoundly about how best to address Islamist terror or invasive migrations, but there is a growing sense of European-ness, a concept that, until recently, appealed only to elites.

Where are we? Against historical odds, the EU has not only survived but thrived. With 510 million inhabitants, the EU boasts a larger population than the USA and Russia combined. Its GDP of $16.5 trillion (2016) is second only to that of the USA’s $18.5 trillion and five trillion greater than that of the People’s Republic of China.

Fumbling attempts to create a viable EU military force have resulted only in flaccid peacekeeping missions, but, given the continent’s history, is the military weakness of traditional aggressors and transgressors much to be lamented? Meanwhile, the EU’s development aid eclipses that of any other state, alliance, or institution.

Will further states quit the EU? Perhaps. Will the Euro fail? No, but economically disadvantaged states may withdraw from the currency (without any thought of quitting the EU). Will the EU regulate itself to death? No. That tide has already turned.

American conservatives have a tradition of criticizing the EU as “socialist,” as a welfare state writ large—a view that is historically myopic. Are peace and prosperity so undesirable? One detects a whiff of resentment at the EU’s success, as though no other child should have a bicycle as fine as ours.

Trade deals come and go. Economies go through cycles. Administrations and governments change. (And democracies ultimately self-correct.) But we have seen, in the EU, one of the most profound shifts in collective behavior that the historical record has to offer. Just as NATO has proven an alliance without precedent and of inestimable value, so, too, has the EU been overwhelmingly positive for its citizens—and for us. Peace is cheaper than war. And fat men don’t fight.

Those war-weary Europeans, some idealistic, others cynical, some both, who came to that “common market” agreement six decades ago started a process whose remarkable consequences none would have dared imagine: enduring peace and startling wealth on a continent that had almost destroyed itself.

As for our trade deficit, build better cars.