- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- California

The “Left Coast” and “Taxifornia” are two common nicknames for the Golden State. And it isn’t surprising why.

California hasn’t voted for a Republican presidential or U.S. Senate nominee since 1988 and hasn’t elected a Republican to a statewide office since 2006. The Golden State’s congressional delegation is currently 74 percent Democratic and the legislative Democrats continue to flirt with a legislative super-majority. Across a range of hot-button policy issues – the environment, abortion, gun control, and immigration – Californians continuously hold left-leaning opinions.

Additionally, the Golden State has the highest personal income tax rate in the country, the highest corporate tax rate west of the Mississippi River, and among the highest sales taxes in the nation. In 2015, California had the 4th latest “Tax Freedom Day” – the date on which Californians have earned enough to pay off their federal, state, and local taxes for the year – and collects the 7th highest income taxes per capita.

That said, however, California is also home to nation’s most defining anti-tax movement – the Proposition 13 campaign. Riding the wave of anti-tax sentiment amidst years of out-of-control property tax assessments, Howard Jarvis showed the California political establishment as well as the nation why being anti-tax could also be good politics. Ever since Governor Brown – then in his first term – flip-flopped on the issue in his 1978 re-election campaign, Proposition 13 has been the “third rail” of California politics.

While it seems impossible that “Taxifornia” and the “Left Coast” can also be the same as the birthplace of anti-tax politics, examining ballot measure results and public polling suggests Californians have decidedly more centrist – even right-of-center – views on taxation. And this has important political and policy implications for those in Sacramento.

Exploring how Californians actually vote when presented with tax-related ballot measures shows that the passage of Governor Brown’s – then in his third term – signature tax increase measure, Proposition 30, is more the exception than the rule. In aggregate, between 1990 and 2012, Californians have rejected tax-related propositions 52 percent to 48 percent.

Examining the details of these measures, however, presents a more nuanced approach Californians have toward the tax issue. For instance, many of these ballot measures decrease taxes in some manner – a position anti-tax proponents would champion. Between 1990 and 2012, Californians have supported tax decrease propositions with almost 57 percent of the aggregate vote while rejecting tax increases and new taxes (43 percent in support). And while Californians have trended left on this issue (support for new taxes and tax increases between 1990 and 2000 was an aggregate 39 percent compared to 47 percent between 2007 and 2012), Californians, despite leaning significantly Democratic in elections, still remain resistant to pro-tax measures.

Moreover, the tax type presents further nuance. Overall, sales and excise taxes and fees, personal income taxes, and corporate income taxes all tend to fail – likely because 81 percent of these ballot measures were tax increases or new taxes. On the other hand, however, property tax measures overwhelmingly succeed – here, because all but one of such measures were tax decreases.

While Californians’ tendency to support tax decreases and oppose new taxes/tax increases appears to run counter to California’s “Left Coast” and “Taxifornia” personality, a look at public opinion polling explains this seemingly sudden shift. When asked to choose between spending cuts and tax increases to address the budget deficit, just 9 percent of likely voters over a decade of public opinion surveys said Sacramento should deal with the deficit via mostly tax increases. Moreover, when asked to choose between higher taxes and more government services or lower taxes and fewer services, a plurality of likely voters (47 percent) have sided with the lower tax option.

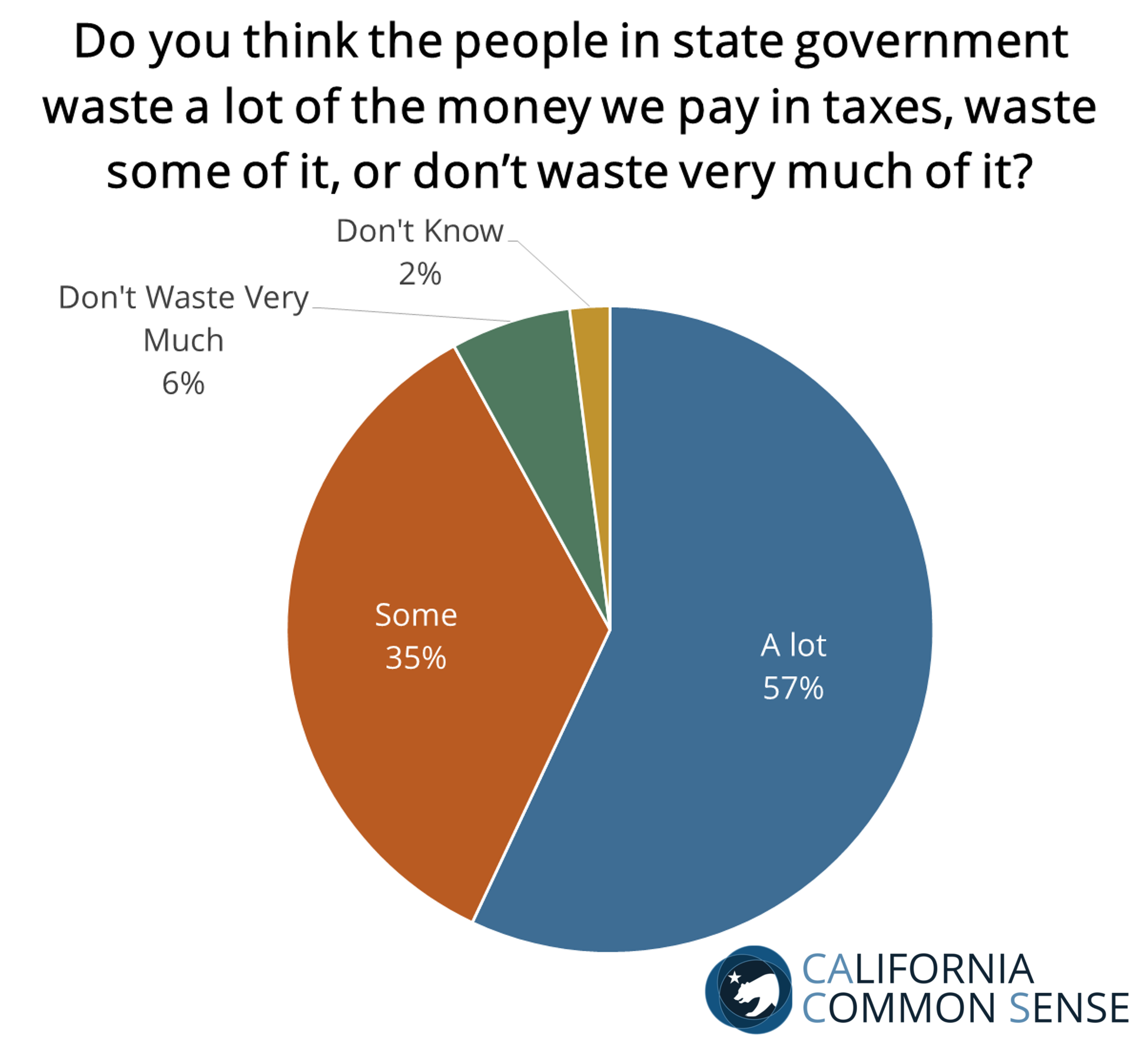

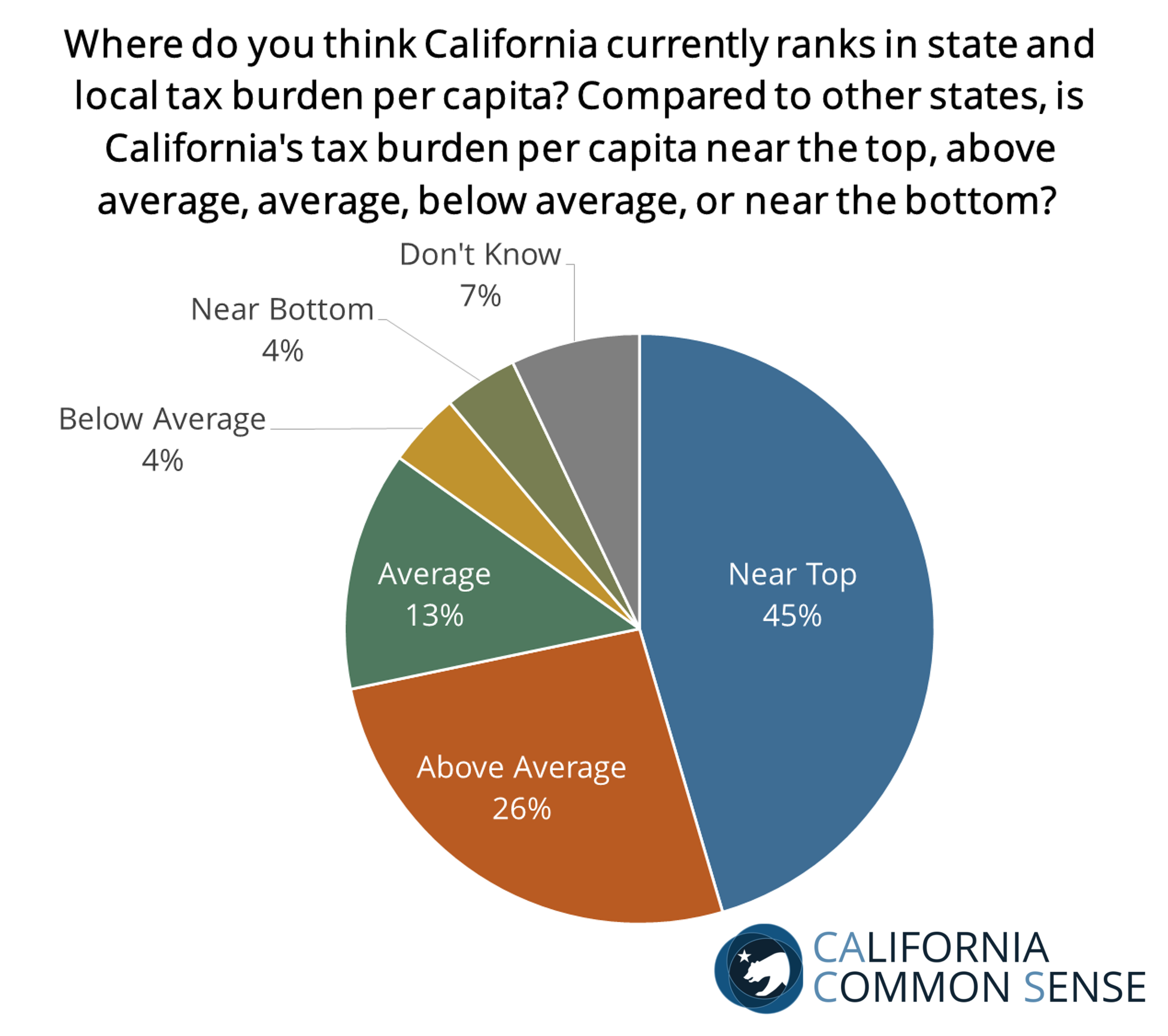

Driving these sentiments are two issues: trust in Sacramento to use taxpayer money wisely and personal belief of their tax burden level. By 12-to-1, likely voters believe Sacramento wastes a lot of the tax revenue Californians pay. This by itself would be a major inhibitor toward passage of new taxes or increasing current taxes. When presented with such options on the ballot, Californians ask themselves why Sacramento should get more money if they are already wasting the revenue they get. But add on top of this sentiment the fact that 53 percent of likely Californian voters believe they pay more in state and local taxes than they should and it becomes clear just how steep tax-related measures face at the polls.

The only solace pro-tax advocates have in seeking public support for more tax revenue is that Californians are concerned about their tax burden more so than they are about California’s overall tax environment. For instance, while 68 percent of likely Californian voters oppose raising the state personal income tax and 65 percent oppose raising vehicle licensing fees, clear majorities are okay with raising corporate taxes or income taxes on California’s wealthy. Moreover, while Californians generally think their tax burden is unfair, a slight majority consider the tax system in totality to be fair.

This has implications, then, for how anti-tax and pro-tax proponents approach Californians on tax-related issues. For one, despite Californians decidedly more Republican-leaning attitudes on taxes, just 32 percent of likely Californian voters have a favorable impression of the Republican Party. While it is possible that the Republican Party’s positions on other issues outweigh their anti-tax position in the mind of centrist Democrat and Independent voters, the party’s struggle on the tax issue could also be framing. Being decidedly purist on tax issues could be off-putting to voters wishing Sacramento would negotiate lasting fixes to California’s many problems. Instead, leading on tax reform in lieu of a doctrinally anti-tax platform could enable the party to capitalize, politically, on Californian public opinion, while also improving California’s inherently volatile tax system, which would be good public policy. For instance, 59 percent of likely Californian voters, including 51 percent of self-identified Democrats and 59 percent of self-identified Independents, believe the state’s tax system needs major changes.

For state Democrats, the situation is just as ominous. While, for the most part, Californians support many of the state Democratic positions, Democratic leaders cannot count on voter support when it comes to their knee-jerk tax increase solutions. While they have had some luck on supporting tax increases for either targeted (and popular) policy areas – like Proposition 30’s focus on K-12 education funding – or on specific demographics – like Proposition 39’s focus on out-of-state corporation – a divide-and-conquer approach to tax increases has its political and policy limits.

In Sacramento – for the foreseeable future – there will continue to be a public battle between the pro-tax Democrats and the anti-tax Republicans. Meanwhile Californian voters will likely continue to confound California’s “Left Coast” and “Taxifornia” nicknames.

Note: Ballot measure analysis aggregates all tax-related ballot measure results between 1990 and 2012 using data from the California Secretary of State’s office. Public polling analysis aggregates likely voter responses from Public Polling Institute of California surveys between January 2004 and May 2015.

Proposition 30

Championed by Governor Jerry Brown to replenish budget crisis-era K-14 education funding cuts, voters passed the $6 billion-a-year tax increase by 11 points in November 2012. It retroactively to January 2012 increased income tax rates through fiscal year 2018-2019 by between 11% and 32% on those making more than $250,000 and increased the state sales tax rate through fiscal year 2016-2017 by a quarter cent. The sunset provisions, Governor Brown’s popularity, and state leaders’ threats to further cut education funding were key to its passage.