- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- The Presidency

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

North Korea’s nuclear weapons confront us with hard choices. We are being urged to make another deal with the North but experience tells us that more and perhaps worse crises would follow. We will do better if we focus on a destination instead of some stopover: to wit, a new leadership in Pyongyang as a step toward the unification of the Korean peninsula under a democratic order.

The North’s weapons pose three dangers. Mounted on its long-range missiles, they could inflict devastation at long distances, including the United States; the threat to Japan is already rousing it to re-arm and could lead to a nuclear-armed Japan—and South Korea as well. Worse still, the regime might sell bombs to terrorists.

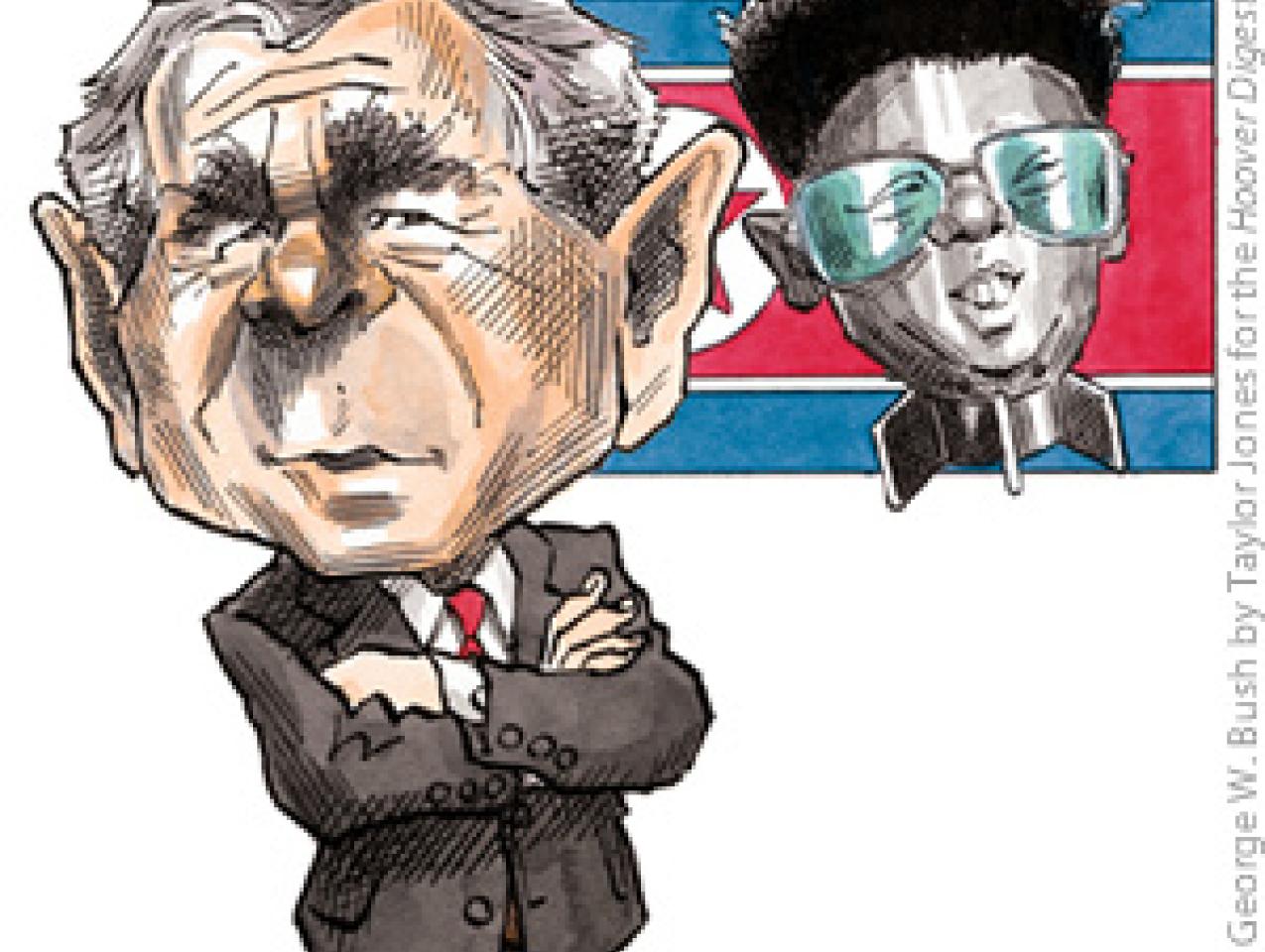

The crisis was set off by the North admitting in October 2002 that it had a secret nuclear weapons program in violation of the 1994 Agreed Framework, which promised economic benefits in return for “freezing” its nuclear program. (It apparently began its secret program in the mid-1990s.) Since openly breaking it, the Kim Jong Il regime has loudly proclaimed that the United States is planning to attack and has demanded a guarantee of security from us. But we are very unlikely to attack without South Korean concurrence, which isn’t in the cards. As for the North starting a war, Kim doesn’t seem to be suicidal.

Kim’s strategic position is weak. Despite some liberalizing steps, the country is an economic basket case, and evidently Kim sees his hold on power as too fragile to stand Chinese-style openness. What’s left is using nuclear weapons for extortion.

Kim might not understand the fire with which he is playing. Despite the inhibitions we have against using force there, a serious prospect of North Korean-originated bombs being detonated in Manhattan could overcome them. Of course, we are not the only concerned party; the Bush administration is rightly treating this as also a problem for Kim’s Asian neighbors. The Japanese see it that way, but what about the South Koreans and Chinese?

Much has changed for the worse between South Korea and the United States. In the past we were aligned with the South’s need to consolidate its democracy and security. With its democracy now solid, the problem is security. Southerners don’t expect the North’s nuclear weapons to land on them or to be the target of nuclear-armed terrorists, but Americans see themselves as endangered both ways. To many South Koreans, especially younger ones, the North is less of a threat than the United States. They also fear that political collapse in the North will cause millions of people to head south and burden them with building the North’s economy. These are worries that South Korea’s friends can help to allay.

China’s position is pivotal. Despite protestations to the contrary, Kim Jong Il could not stay in power without at least its tacit support. China’s leaders don’t want a communist regime to collapse, a flood of refugees, a war that might bring American forces to the Yalu River, or a re-armed Japan. They say they oppose the North’s nuclear programs, but, despite having the power to end them, they have not done so, which could lead to the undesirable outcome of three more nuclear-armed neighbors, two in Korea plus Japan.

What should we do? A new deal allowing more intrusive inspections would be incompatible with the character of North Korea. Some argue that we should negotiate anyway, suggesting that this would “buy time” during which something good might happen. Given our options, that argument should not be rejected out of hand. But how much time might we “buy”? The record suggests very little; agreements or no, Kim Jong Il will not give up his nuclear weapons.

As Nicholas Eberstadt puts it (Weekly Standard, November 29, 2004), we need a better class of dictator running North Korea. A Park Chung Hee or a Deng Xiaoping would mean economic liberalization and a step toward political liberalization—and eventual unification. The Chinese would surely prefer that to the consequences of Kim remaining in power.

That brings us full circle to the assets the United States might bring to bear, raising the question of how we have dealt with the many other economic, political, and security issues we have with China. Putting them all on the table together might change the dynamics of our relationship. If the Chinese government realizes that we won’t deal with North Korea, that the Japanese will react negatively, and that we will try to bring about Kim’s removal, it might decide to do something decisive about the North.

We also need to have a frank discussion with South Korea. On the one hand, we should offer to help it with the burdens that might emanate from a destabilzed North; on the other, we should make it clear that it cannot have U.S. protection while sustaining a regime that threatens us.

If the American government focuses on a goal and devises a long-term strategy, it can do remarkable things. Here is a challenge to it of a high order.