- History

- US

- Contemporary

In the course of the American revolutionary war, the New York-based lawyer and political pampleteer John Stevens observed that "The path we [Americans] are pursuing is new, and has never been trodden on by man." That well-founded sense of originality was accompanied by remarkable confidence in our abilities and optimism about our future. In the historian Bernard Bailyn’s words, "The Founding Fathers were disposed in the upheaval of the Revolution to find in this diminished provincial world, not deprivation, but the sources of new advantages."

That confidence and optimism have persisted for more than two centuries, along with the belief that in America, the founders created something original, exceptional. The notion of American "exceptionalism" has given America and Americans a continuously recognizable, unique character; an essential continuity alongside the radical changes in our economy, democracy, demographic make up, and place in the world during the last two centuries.

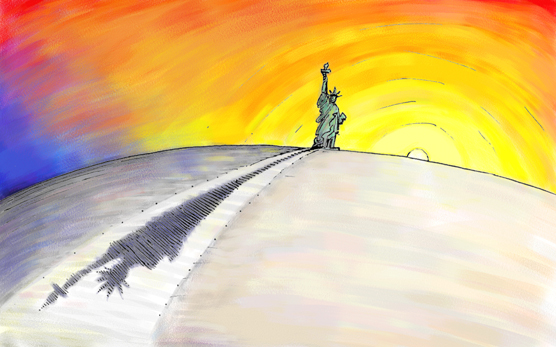

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

Unlike his presidential predecessors, Barack Obama has a different view of American exceptionalism. He has stated that while Americans think America is exceptional, he is equally sure that the "Brits and Greeks" think they are exceptional. Obama is not only exceptional in being the first African-American president, but in thinking that America is unexceptional.

President Obama’s implicit rejection of our "exceptionalism" prompts me to reemphasize what has made us not only different, but exceptional, and exceptional in ways that go beyond power, wealth and size.

To begin with, as Bailyn stresses, in a single generation, in one of the most unlikely places—the eastern shores of British America—the founders created the first democratic republic in world history. Quite clearly, other democratic republics have appeared since then, so one must ask is there something about our democratic republic that has remained unique over time. The answer is yes!

In his wonderful book "Empire of Liberty," Gordon Wood stresses that from our beginning , "America was [above all else] the land of liberty." He goes on to note that: "Americans have always been a vigilant people, jealous of their liberty, as Edmund Burke had noted, ‘sniffing tyranny in every tainted breeze’….a people who developed a keen sense of their own worth—a sense that living in the freest nation in the world they were anybody’s equal."

In a single generation, in one of the most unlikely places—the eastern shores of British America—the founders created the first democratic republic in world history.

This character defining emphasis, belief in, and demand for individual liberty with all the debate, conflict, and violence it has entailed in the course of American history, has created a nation unlike any other in the world.

The ideal basis of our way of life is a nation in which the individual citizen, believer, and entrepreneur exercises his and her liberty. In the first place, that means the liberty to move and seek a better life. From the eighteenth century on, all observers, domestic and foreign, noted the remarkable geographical restlessness of Americans. We are even unique in "sending our children away to college," for instance. Americans can also exercise their liberty by improving their material life through commercial activity, and by adopting a new identity.

The immigrant character of America is unique in two respects. In The Gilded Age, historian Sean Dennis Cashman points out that the very word "immigrant" was invented by Jedidiah Morse in 1789 to describe foreign settlers in New York. By calling them "immigrants rather than the more traditional emigrants Americans emphasized the fact that newcomers had entered a new land [and identity] rather than [merely leaving old one[s]."

The outcome of immigration to the United States was equally unique. Throughout our history the e pluribus of immigrants have assimilated to an American unum. A personal example: I grew up in an Irish Catholic working class family in an Irish Catholic neighborhood and attended an Irish Catholic school.

When it came time to decide where to go to college, I chose Columbia over Catholic schools. A disgruntled relative pointed out to me that there were only Communists and Jews at Columbia. As it turned out, I went to Columbia, studied Communist countries, and eventually married a woman who is half-Jewish. Still, we live in Ireland several months each year.

America’s Anglo-Protestant culture has been the source of its liberty and prosperity.

At the end of his presidency, looking at the country he helped create, George Washington said: "With slight shades of difference, you have the same religion, manners, habits and political principles." This has remained true for two centuries. As Samuel Huntington pointed out in "Who We Are: America’s Great Debate," immigrants of "all races, ethnicities and religion accepted Anglo-Protestant culture, traditions and values" when they came to America. This Anglo-Protestant culture, he correctly concluded, has been the source of American "liberty, unity, power, prosperity and moral leadership as a force for good in the world."

A final feature of American exceptionalism has been the persistent belief that America is a model for the world; a belief that has taken two very different forms. The first pragmatic form views America as an exemplary model of liberty, a model the world can adapt to its own circumstances. The second utopian form views America as an obligatory model to be imposed upon the world, and then adapted to local realities. Both positions held to James Madison’s belief "in the capacity of man for self-government."

Though exceptionalism has defined our history for 200 years, there have always been threats to it.

Today, one pointed challenge to our political culture of individualism is the ideology of multiculturalism and its embedded presence in colleges in the form of ethnic and racial studies program. This multiculturalism says you must maintain the primacy of your group identity or risk becoming white, or anglo—it is an ideology that elevates the group’s identity over individual identity.

Another threat to our exceptionalism has been the periodic concentration of wealth in banks and in industrial and financial institutions. Their correspondingly disproportionate influence on the government ultimately disenfranchises the individual citizen and entrepreneur. "The day of combination is here to stay. Individualism has gone never to return." Karl Marx didn’t say this; John D. Rockefeller did, speaking over a hundred years ago.

However, the greatest threat to our "exceptionalism" comes when government sees liberty and equality as its gift to its citizens. The current presidential administration not only denies American exceptionalism; it is attempting to reconfigure relations between the people and the government so as to undermine it.

In his 1846 treatise "On Liberty," John Stuart Mill explained this very fact. As government grows, the very principle that defines American exceptionalism wanes: self-government.

Every function superadded to those already exercised by the government…converts more and more, the active and ambitious part of the public into hangers on of the government…if the employees of all these different enterprises were appointed and paid by the government and looked to the government for every rise in life, not all the freedom of the press and popular constitution of the legislature would make this or any other country free otherwise than in name.

According to Mill whatever "crushes individuality is despotism by whatever name it may be called and whether it professes to be enforcing the will of God, or the injunctions of men."

Today there are many such "men," in and out of government, driven by ego, envy, entitlement, and elitism—people for whom equality is not simply equality of opportunity, but rather, as de Tocqueville noted, "a depraved taste for equality which impels the weak to attempt to lower the powerful to their own level and reduces men to preferring equally slavery to inequality with freedom." Such a notion of equality creates, in the form of government, "an immense tutelary power…absolute, detailed…mild…It provides for the citizens security…conducts their principal affairs, directs their industry, regulates their estates, divides their inheritance, can it not take away from them...the trouble of thinking and the pain of living?"

We have been, at least to date, exceptional in being a self-governed democratic republic firmly based on individual liberty. That liberty is the guarantee of our continual progress. As Mill observed: "the only unfailing and permanent source of improvement is liberty, because there are as many possible sources of improvement as there are individuals." Government can erase that liberty because it tolerates only one source and definition of improvement—its own.