- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Campaigns & Elections

- Energy & Environment

- Economics

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

In announcing recently that the Fairness Doctrine would be wiped off the books, the Federal Communications Commission took one small step into the information age. Characteristically, the commission was decades behind the times, and it left other media regulation still stuck in the industrial age and in serious need of rethinking.

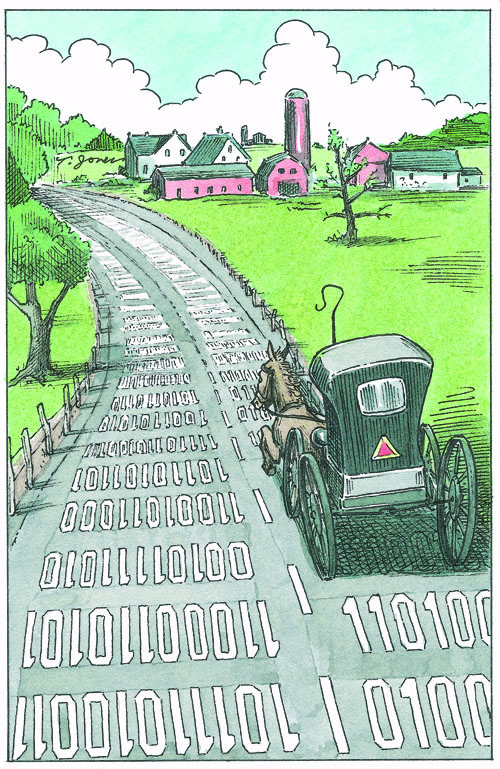

A major problem with government regulation of business is that it is based on markets and technologies as they exist when the rules are imposed. In the case of radio, this body of law has largely been the Radio Act of 1927, the Communications Act of 1934, and the Fairness Doctrine adopted by the FCC in 1949. There were fewer than three thousand radio stations in the country in 1949, compared to the fourteen thousand that ply today’s robust and competitive market.

The Fairness Doctrine required radio stations to air opposing points of view. So, for example, if a radio host or guest favored a particular policy, the station was obligated to air a message against. Perhaps this made some sense when a geographic market had few stations, but today, with satellite radio, Internet radio, and thousands more terrestrial stations, every point of view under the sun can find its way onto the air. For decades, the market itself has provided protection for minority points of view, so the primary question should be why it took government so long to catch up to market realities.

If the Fairness Doctrine were enforced today, there would be no Rush Limbaugh, no Sean Hannity, no talk show hosts with a point of view. Whether you enjoy their programs or not, these radio talkers have rescued and re-energized talk radio. If a listener wants balance or fairness, he or she can simply turn the dial to another station whose talkers have a different point of view. Rather than diversity on every program, there is a diversity of programs and even a variety of distinctive stations and networks—a market that achieves the same fairness goals intended by the outdated Fairness Doctrine.

In the end, like many government regulations, the Fairness Doctrine had become a political football as much as an agency rule. The FCC suspended it during the Reagan years but didn’t take it off the books. Then for years, concerned about the rise of conservative talk radio, Democratic leaders in the House and Senate threatened to put it back in force. Finally it died as part of President Obama’s push to satisfy business that he was seeking to streamline government and eliminate unnecessary regulation. Even now, the moldering regulation doesn’t seem fully dead. Some of the Occupy Wall Street protesters, for instance, have called for reinstating it. Such is the life of federal regulatory schemes.

What federal agencies in general, and the FCC in particular, need to be concerned about is whether federal regulations continue to make sense as markets and technologies develop. In that sense, eliminating the Fairness Doctrine was no better than a baby step into the information age. What about the equal time rule, a kind of companion to the Fairness Doctrine? It requires that if one candidate for an office appears on the broadcast media, other candidates must be given equal time. This rule also is anachronistic and has been so swallowed up in exceptions as to be meaningless. If Donald Trump had run for president, for example, his appearances on The Apprentice might require equal time for other candidates, unless the show were on cable television, which is a meaningless distinction in these days of cable and satellite TV. If a candidate sits down for a few minutes with Letterman or Leno, another exception for “news/interviews” illogically comes into play. Isn’t it time for equal time to go the way of the Fairness Doctrine?

And how about government subsidies and funding for public broadcasting? Again, the support may have made sense when there were only three or four television networks. If there’s a need for public broadcasting’s programs today, shouldn’t they compete for funding and airtime with everyone else? I find little justification for a nearly bankrupt government to spend money on television and radio programming when we live in a 24/7 media cycle. Yet taxpayers continue to provide more than $400 million for public broadcasting, roughly 15–20 percent of its budget, and some executives in that business make more than the president of the United States. Further, it drags the government directly into questions of political content, exemplified by the controversy surrounding commentator Juan Williams and the termination of his contract by National Public Radio. The bipartisan budget deficit commission recommended phasing out taxpayer subsidies to public broadcasting.

So, one cheer for the FCC for burying the Fairness Doctrine. But let’s hold off on three cheers until more work is done to align government policy toward the media with the market realities of the media age in which we live.