PARIS—On Jean Monnet Square, which commemorates the founding father of the European Union in the heart of Paris’s swankiest district, there is the most elegant McDonald’s I have ever seen. The crimson woodwork exterior proclaims in large letters that this is a Restaurant, with fin de siècle lamps setting off the impeccably discreet golden arches. Inside, there is a display cabinet that contains—beside the Action Man and “Betty la Malice” figurines—a photograph of Victor Hugo, the text of a poem by Victor Hugo, and display copies of his Hernani and Le dernier jour d’un condamné. You don’t get that at your McDonald’s in Kansas City.

As if to refute the angry claims of European anti-globalizers about exploitative, insecure “McDonald’s jobs,” there are leaflets on display—I have one before me as I write—explaining how McDonald’s France is a socially minded employer, all of whose work contracts are of unlimited duration, with wages determined by a group bargaining arrangement for the restauration rapide sector.

Stepping out onto the Avenue Victor Hugo (hence the Hugoiana in the display cabinet), my eye is caught by one of those impossibly chic young women who stroll around the 16th arrondissement, visiting its fashion boutiques, little restaurants, and leafy private streets. She is just saying to her companion, “and then it turned out he was an American!”

Round the corner, a bust of Voltaire looks down from the wall of the Lycée Janson on to a shop called USA Concept Sport. A little farther up the Rue de la Pompe, Racine and Molière gaze stony-eyed at another sportswear shop called Compagnie de Californie. Of course the lycée students wear trainers, baseball caps, and T-shirts (I ![]() NY). Peeping inside the courtyard of the lycée I spy . . . a basketball court.

NY). Peeping inside the courtyard of the lycée I spy . . . a basketball court.

On the way back to my hotel, I pass one of those characteristically Parisian dark-green display stands advertising a film called Comment se faire larguer en 10 leçons (that is, a subtext helpfully explains, “How to lose a guy in 10 days”—American, of course). I ring the office of the think tank Notre Europe to arrange an appointment with its president, Jacques Delors—the Jean Monnet of the 1980s. They put me on hold, and the canned music down the line is “All That Jazz,” sung in American English.

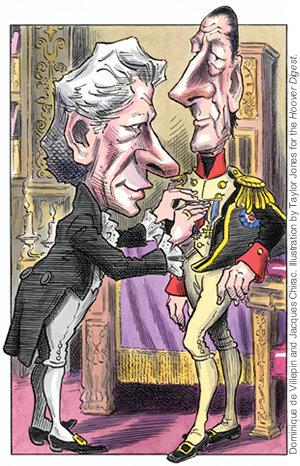

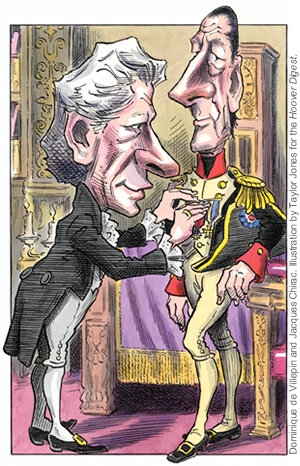

The French intellectual and Academician Jean-François Revel has recently written a fine book about French anti-Americanism entitled L’obsession anti-américaine. But one could also say simply “the obsession with America.” French resistance to Americanization is so sharp because the Americanization of France is so far advanced. There is, crudely put, a sense that on all fronts the Americans are winning and the French losing. The most eloquent spokesman of this spirit of doomed but glorious resistance is Dominique de Villepin, who is both the French foreign minister and a prolific writer of literary, historical, and political nonfiction.

Looking for his latest on the nonfiction table at a Paris bookshop, I first encounter Emmanuel Todd’s political bestseller Après l’Empire, which suggests that the United States is an empire in decline (hence, perhaps, the book’s popularity in France) and illustrates what he considers the deep, irreconcilable cultural difference between Europeans and Americans by “the position of the American woman, castrating and menacing [castratrice et menaçante], as worrying for European males as the omnipotence of the Arab man is for European females.” (Did he, one can’t help wondering, have some unmentionable experience with a Texan belle?) Next to it there is Mon histoire by Hillary Rodham Clinton (castratrice et menaçante?), John McEnroe’s Vous êtes sérieux? and two books about the dark secrets of the Bush administration.

Then, finally, I find my de Villepin. In the gloriously old-fashioned, discreet cream livery of Gallimard’s nrf series, with nothing so vulgar as a cover photograph, the title is emblazoned in that pleasing traditional crimson, not dissimilar to the color of the woodwork at the Jean Monnet McDonald’s. “Eloge des voleurs de feu,” it says, which might loosely be translated as “Hymn to the thieves of fire.” It contains 823 pages of learned, high-flown, flowery reflections on the glorious if doomed role of the poet in a nasty world, with a high incidence of exclamation marks. Its hero is Rimbaud, from whose Season in Hell he quotes the lines Feu! Feu sur moi! Là! (“Fire! Fire on me! There!”). The invitation is to the poet’s ammunition—words—to fire back at him, but I’m sure Donald Rumsfeld would also be happy to oblige. And this is only de Villepin’s literary production for 2003.

In 2002, he published The Cry of the Gargoyle, a plangent appeal to France to rouse itself from “the temptation of resignation that threatens a nation as torpor overcomes it. . . . For many abroad, the French funeral has already been held!” In 2001 he published Napoleon—the Hundred Days, an eloquent celebration of Bonaparte’s last, heroic, doomed attempt to recapture power.

There is, you will notice, a common leitmotif here. And you can see how a 49-year-old professional French diplomat of aristocratic origin and traditional, literary education might reach this point of romantic defiance. After all, France has been one of the world’s greatest cultural-political losers of the last 200 years. I say this, unlike many in Washington today, without a trace of schadenfreude. In 1783, the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin held a competition for the best explanation of why French would become the universal language. But it didn’t happen that way. Nelson and Wellington did for Napoleon. The Americans chose to speak English. France was defeated by Germany in 1940, while Britain just held out.

In the Cold War, France fought a magnificent diplomatic rearguard action—one of the finest in history—to reestablish through the project of European union its position as a leading world power. But since the end of the Soviet Union, that has faltered too. With the eastward enlargement of the EU next year, Germany will be at its center, and France will no longer be able to call the shots—even if a Frenchman has drafted the new Europe’s constitution. Culturally, linguistically, economically, socially, America is in the ascendant. The British, of all people, should be able to imagine what it must feel like to be French today. After all, if Napoleon had won, and the United States had decided to speak French, then Britain’s former foreign minister Douglas Hurd (though not, I think, current foreign minister Jack Straw) might today be penning his own Hymn to the Thieves of Fire.

To find themselves, therefore, apparently at the head of a European resistance movement against Washington’s policy over the Iraq war was a quite unexpected thrill for Chirac and de Villepin. But it brought out in them an arrogance, underpinned by deep insecurity, which has infuriated their partners not just in Washington but in Madrid, Warsaw, Rome, London, and many smaller capitals. Now they need to be helped down from their high horse. We should assist them.

Anyway, to spend a few days in Paris is to be reminded of everything that is good and worth defending in France—the beauty, intellectual ambition, grace of life, and civility. We need the French in Europe, and not just to make the most civilized McDonald’s in the world. So I say, without any of the irony that George W. Bush, speaking to a French journalist before his recent trip to Evian, imparted to the phrase, Vive la France!